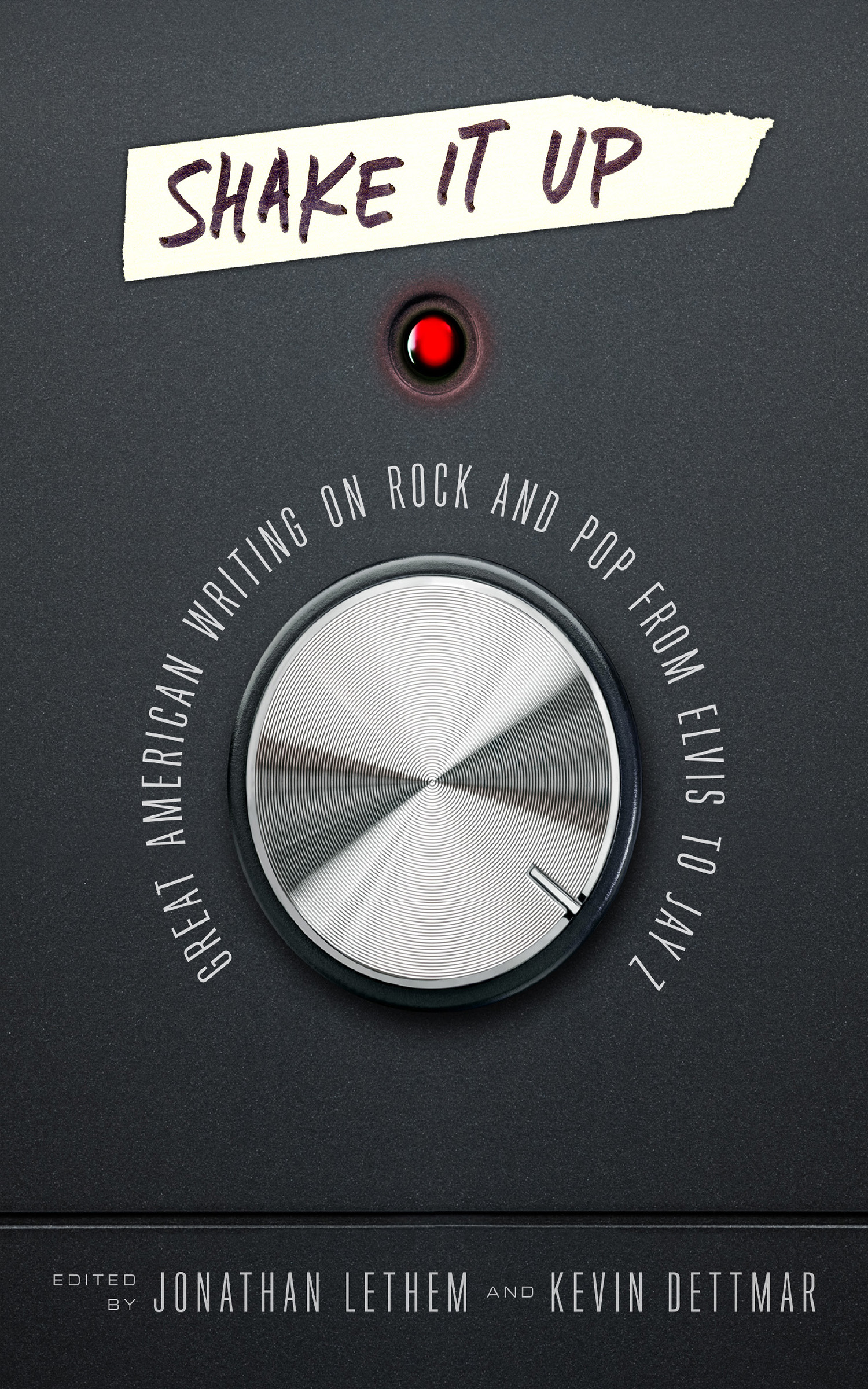

S HAKE I T U P

GREAT AMERICAN WRITING ON ROCK AND POP FROM ELVIS TO JAY Z

Edited by

Jonathan Lethem

and Kevin Dettmar

A Library of America Special Publication

Volume compilation copyright 2017 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

Introduction copyright 2017 by Jonathan Lethem and Kevin Dettmar

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Distributed to the trade in the United States

by Penguin Random House Inc.

and in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about Library of America and to explore our popular Story of the Week and Moviegoer features.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2106959719

ISBN 9781598535310

eISBN 9171598535327

First Printing

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

Introduction

F IFTY S ELECTIONS from fifty writers covering approximately fifty years of American rock and pop writing: its an elegant conceit, youve got to admit. One writer from each of the fifty states, though, proved a bridge too far. Nevertheless, the origin of the practice of writing about the American popular music known as rock n rolla music which, as this books contents suggest, would come to encompass elements of variants like rhythm and blues, soul, bubblegum, doo-wop, and, later, art rock, funk, punk, glam, disco, heavy metal, and hip-hopis as distributed, as mongrel, and as intimate as the origin of the music itself.

The music this writing took as its subject emerged over a period of decades, a prodigal stepchild of jazz and the blues, then abruptly coalesced into a teenage sensation in the mid-50s apotheosis of Fats Domino, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, and their cohort. At that moment it became, as much as comic books, the epitome of a vernacular popular culture that was decried, mocked, and ignored, often simultaneously. That the new forms, even when played by whites for whites, unmistakably had roots in black cultural styles hardly went unnoticed, even when it went unspoken; a terror of cultural miscegenation lay behind the scorn. That it should find itself the object of critical response within a decade of its birth might seem miraculous, under the circumstances, but it wasnt the subject of criticism at its inception. Early assessments of this musics value were in the hands of the users; a DJ flipping a 45 to discover a preferred B-Side was engaged in a critical intervention on behalf of an audience he inferred and a tradition he was helping create. Even the phrase The British Invasiona marketing concept that was also a clarion cryimplies some critical-historical awareness, the birth of a language for declaring that these disposable artifacts could be ordered into legacies of influence and impact.

In getting itself on its feet, the field of rock and pop writing resembled the music that inspired it. In both cases, a tiny handful of practitioners working in eccentric isolation became a story of the invention of an embracing collective idea. Think of Sun Records producer Sam Phillips in Memphis, or Crawdaddy magazine founder Paul Williams mimeographing in his Swarthmore dorm room, each generating a lonely signal that would inspire thousands of others. The writers who in the mid-60s began to cobble together the tradition reflected in this anthology started as fans, and the magazines in which they published were, to begin with, fanzines or underground newspapers: Crawdaddy, Mojo-Navigator, and Rolling Stone.

Like the musicians, these writers gained their sense of possibility from available parts. These included their immediate predecessors in the lively zine traditions of the folk music, jazz, and science fiction demimondes, as well as the hybrid New Journalism of writers like Gay Talese and Tom Wolfe, and pop-acute film criticism like that of Pauline Kael. In this regard, the early rock magazines were founded on the presumption of a counterculture, even if it was one partly being wished into existence by writers and publishers. Rolling Stone, exceptional for its (successful) commercial aspirations, declared in its first issue that it was not just about the music, but about the things and attitudes that music embraces.

Among the utopian notions in the air was an aesthetic proposition: that the pop music of the time might not only be the next great American art form, but that it might be so precisely because of the elements that had made it eligible for sneering dismissal by an older generation. And further, that some version of community was implicit in the artworks themselvesa community founded less on political axioms than on instantaneous recognition of sensory revelations. You had not only to hear the music, but to actually trust what you heard.

An attitude therefore not of defensiveness, but of revolutionary and often joyous defiance, is forged in the prose of the early rock writers. Sometimes these were close readerslike Robert Christgau, and others like him, with degrees in Englishmaking explicit claims that the songs could sustain and reward persistent study. Other times they were dropouts staking all they had on the belief that rock n roll was part of a new and necessary language for living in the world. In any case, the stakes were high. Even the Dada-interventionist writer Richard Meltzer, whose mock-heroic exegeses of songs by the likes of The Trashmen mocked the academicization of pop before it had begun, stands as confirmation of the aspirations he satirizes.

The earliest writing collected here displays how this scattering of excitable utterances became an actual living discourse. With a startling quickness, these writers (nearly all white and all men at the outset) formed a loose guild of working journalists. Rolling Stone and The Village Voiceand soon Creem, and a revived Crawdaddy, and othersmade possible, for a while, a rich professional era, one corresponding to what in retrospect was a long heyday for the music industry itself in the 70s and 80s into the 90s. Major newspapers all had working pop critics, and there were many major newspapers; slick magazines, both monthlies and weeklies, joined the party too. As utopian assumptions and capitalist imperatives together dissolved the quarantine between counterculture advocacy and mercantile media, writers like Paul Nelson and Jon Landau began working directly with musical artists on behalf of record labels or management companies.