Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Michael Ray, Assistant Editor, Geography and Popular Culture

Rosen Educational Services

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Karen Huang: Photo Researcher

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Michael Ray

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

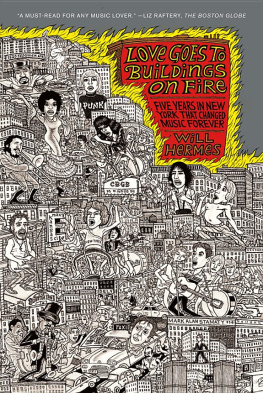

Disco, punk, new wave, heavy metal, and more : music in the 1970s and 1980s/edited by Michael Ray.1st ed.

p. cm.(Popular music through the decades)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-912-2 (eBook)

1. Popular music1971-1980History and criticism. 2. Popular music1981-1990History and criticism. I. Ray, Michael.

ML3470.D57 2013

781.6309'047dc23

2012032630

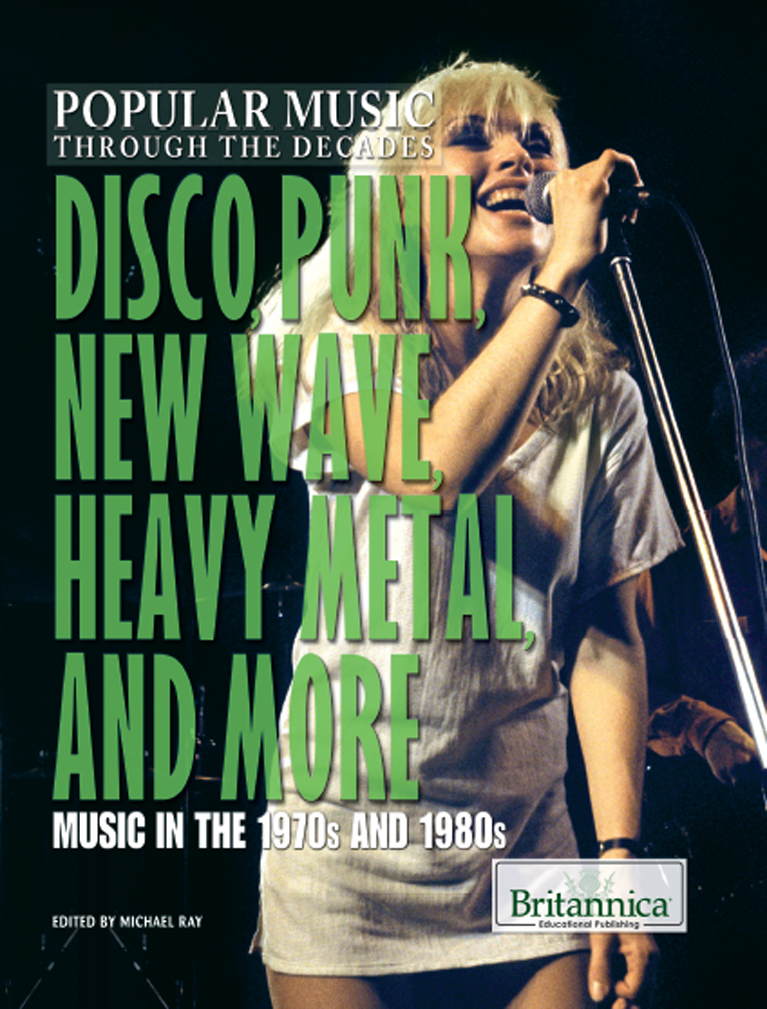

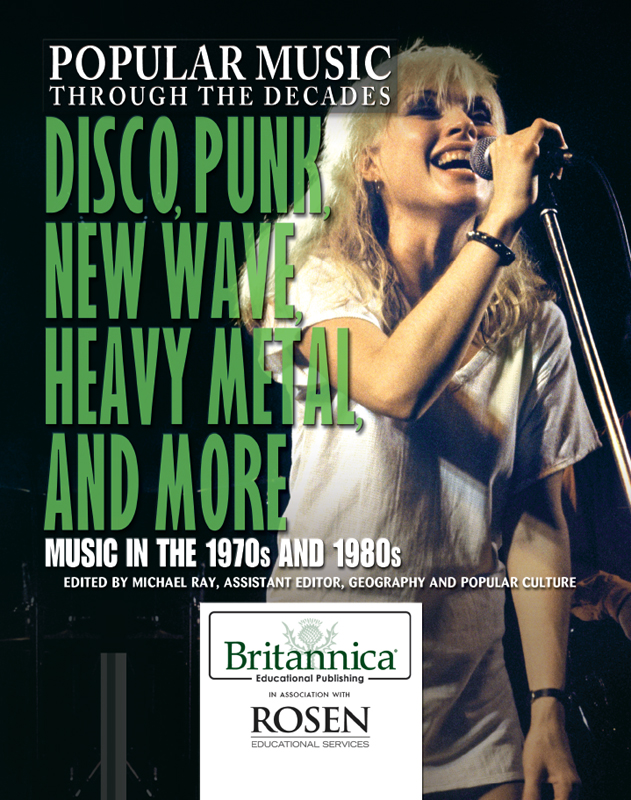

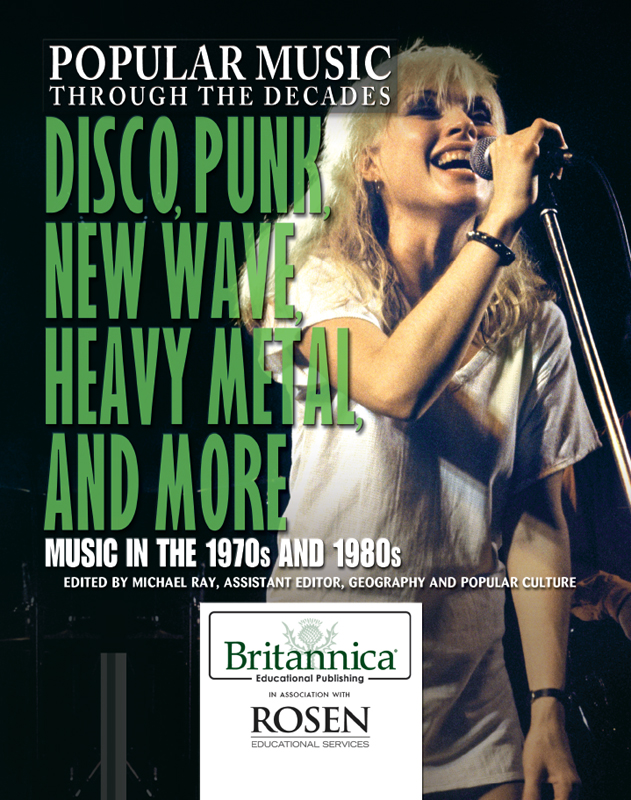

On the cover, p. iii: Singer Deborah Harry of the new wave band Blondie performing at the Roundhouse in London, 1978. Denis ORegan/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Pages 1, 11, 38, 55, 66, 105, 118, 126, 136, 143, 148, 165, 178 Ethan Miller/Getty Images (Fender Stratocaster guitar), iStockphoto.com/catrinka81 (treble clef graphic); interior background image iStockphoto.com/hepatus; back cover iStockphoto.com/Vladimir Jajin

CONTENTS

G iven the variety of musical trends that rose and fell throughout the 1970s, one could say that the 70s didnt so much begin as the 60s ended. The peace and love atmosphere of the Woodstock era came to a violent conclusion at the Altamont festival in Livermore, California, on December 6, 1969. The free concert, organized by the Rolling Stones as a token of appreciation for their fans, was marred by violence on a widespread scale. Much of it was instigated by the Oakland chapter of the Hells Angels, an outlaw biker gang that had been hired by the Stones to provide security for the event. While the consequences of this decision became apparent relatively quickly, the Stones initially had few concerns. Just a few months earlier, they had contracted a U.K. chapter of the Angels to provide security for a free concert in Londons Hyde Park. Whats more, the Angels had been a presence in the Bay Area scene for years. They were associated with American writer and 60s counterculture icon Ken Keseys Merry Pranksters (who provided the Angels with LSD) and had served as unofficial security guards at previous concerts.

At Altamont, however, things turned ugly quickly. Beatings were frequent and indiscriminate. Marty Balin of the Jefferson Airplane was struck unconscious when an Angel with a pool cue assaulted him. Parts of the crowd took to the stage in an effort to escape the ongoing melee. The show reached its tragic, and perhaps unsurprising, climax during the Stones set, when a pair of Angels stabbed a member of the audience to death. But this was not the only death to herald the dawn of the 70s.

Rocks decade of decadence began with the figurative and sometimes literal demise of numerous pioneers of the 60s. The Beatles broke up in early 1970, and their final album, Let It Be, was, in essence, released posthumously. Guitar legend Jimi Hendrix died of a drug overdose in September of that year. Janis Joplin died less than three weeks later. The Doors lead singer Jim Morrison died in Paris the following summer. In its relatively short history, rock had already witnessed the passing of its share of luminaries, but the loss of Hendrix, Joplin, and Morrison in such quick succession was a shock. In later years, fans would speak of a Forever 27 curse, as each artist died before his or her 28th birthday (the Forever 27 club would ultimately claim additional members, such as Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse).

But in rock, artists can achieve some measure of life after death. Hendrix, Joplin, and Morrison each left an enduring legacy, and even the survivors of the 60s did not emerge from the decade untouched. The Rolling Stones were a changed band; the death of founding member Brian Jones (himself an inductee of the Forever 27 club) in July 1969 and the Altamont fiasco signaled a shift for both the Stones and bands to come. No longer would Mick Jagger serve as rocks dark jester, the bands brushes with the law becoming a thing of the past. The Stones of the 70s were a corporate juggernaut, a well-oiled rock machine designed to fill stadiums. Indeed, the Rolling Stones proved to be one of the most successful touring bands of all time, with a career that would ultimately span more than half a century. Notable, however, was a claim by Keith Richards that he had not set foot inside Jaggers dressing room over the last 20 years of that time. Thus, it was with one of the biggest surviving acts of the 60s that the mood of the 70s was set. Flower power was a thing of the past. Turn on, tune in, drop outthe mantra of American psychologist, author, and LSD-advocate Timothy Learycould now be concluded with cash in.

This is not to say that the 70s were a decade devoid of artistic merit. On the contrary, vibrant new talents were emerging in the center of the rock spotlight as well as at its fringes. Led Zeppelin took the psychedelic-blues fusion that had characterized the early Rolling Stones and melded it with a wild mixture of European and Eastern influences. Singer Robert Plant and guitarist Jimmy Page built on the Jagger and Richards dynamic to such a degree that their individual styles would provide a formula for entire genres that were to follow. Pages guitar work was virtuosic without being excessive, and Plants vocals, which ranged from a virtual whisper to an animalistic howl, set the standard for generations of hard rock and heavy metal bands. Plant would also serve as the visual archetype for the heavy metal front man, exhibiting unbridled sensuality and sporting a wild mane of hair.

Seizing upon the success of Zeppelin and incorporating influences from the burgeoning glam rock scene, Queen burst into the limelight with anthemic singles powered by Brian Mays stellar guitar work and front man Freddie Mercurys nimble vocals. While Plant exemplified the rock star as sex symbol, Mercury was a consummate show-man, exhibiting a stage persona that was equal parts substance and spectacle. Beneath Mercurys flamboyant exterior was a skilled songwriter and multi-instrumentalist who possessed the uncanny ability to command a crowd of tens of thousands of people. Neither Led Zeppelin nor Queen were afforded the level of critical examination that was applied to the Beatles or the Stones, but both bands were enormously popular, and each crafted a body of work that remains surprisingly fresh today.