Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov - Principles of Orchestration

Here you can read online Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov - Principles of Orchestration full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1964, publisher: Dover Publications, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Principles of Orchestration

- Author:

- Publisher:Dover Publications

- Genre:

- Year:1964

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Principles of Orchestration: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Principles of Orchestration" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

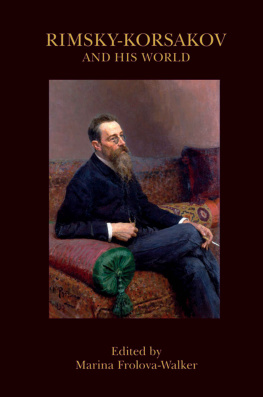

To orchestrate is to create, and this cannot be taught, wrote Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, the great Russian composer whose genius for brilliant, highly colored orchestration is unsurpassed. But invention, in all art, is closely allied to technique, and technique can be taught. This book, therefore, which differs from most other texts on the subject because of its tremendous wealth of musical examples and its systematic arrangement of material according to each constituent of the orchestra, will undoubtedly be of value to any music student. It is a music classic, perhaps the only book on classical orchestration written by a major composer.

In it, the composer aims to provide the reader with the fundamental principles of modern orchestration from the standpoint of brilliance and imagination, and he devotes considerable space to the study of tonal resonance and orchestral combination. In his course, he demonstrates such things as how to produce a good-sounding chord of certain tone-quality, uniformly distributed; how to detach a melody from its harmonic setting; correct progression of parts; and other similar problems.

The first chapter is a general review of orchestral groups, with an instrument-by-instrument breakdown and material on such technical questions as fingering, range, emission of sound, etc. There follows two chapters on melody and harmony in strings, winds, brasses, and combined groups. Chapter IV, Composition of the Orchestra, covers different ways of orchestrating the same music; effects that can be achieved with full tutti; tutti in winds, tutti pizzicato, soli in the strings, etc.; chords; progressions; and so on. The last two chapters deal with opera and include discussion of solo and choral accompaniment, instruments on stage or in the wings, technical terms, soloists (range, register, vocalization, vowels, etc.), voices in combination, and choral singing.

Immediately following this text are some 330 pages of musical examples drawn from Sheherazade, the Antar Symphony, Capriccio Espagnol, Sadko, Ivan the Terrible, Le Coq dOr, Mlada, The Tsars Bride, and others of Rimsky-Korsakovs works. These excerpts are all referred to in the text itself, where they illustrate, far better than words, particular points of theory and actual musical practice. They are largely responsible for making this book the very special (and very useful) publication it is.

This single-volume edition also includes a brief preface by the editor and extracts from Rimsky-Korsakovs 1891 draft and final versions of his own preface, as well as an appendixed chart of single tutti chords in the composers works.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: author's other books

Who wrote Principles of Orchestration? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.