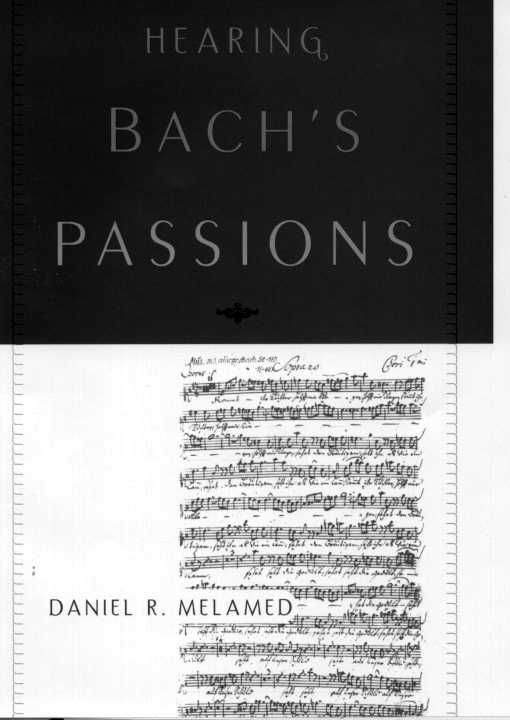

Hearing Bach's Passions

Daniel R. Melamed

HEARING BACH'S PASSIONS

This page intentionally left blank

HEARING BACH'S PASSIONS

Daniel R. Melamed

Preface

Bach's passion settings, approaching three hundred years old, have become intimately familiar from dozens of recordings and countless performances, but today we hear them distantly removed from their original contexts. Bach wrote them for a particular liturgical event at a specific time and place; we hear them hundreds of years later, often a world away and usually in concert performances. Early eighteenthcentury conceptions of vocal and instrumental ensembles shaped those first performances; we usually hear the passions now as the pinnacle of the choral/orchestral repertory, adapted to modern forces and conventions.

Bach's passion settings, approaching three hundred years old, have become intimately familiar from dozens of recordings and countless performances, but today we hear them distantly removed from their original contexts. Bach wrote them for a particular liturgical event at a specific time and place; we hear them hundreds of years later, often a world away and usually in concert performances. Early eighteenthcentury conceptions of vocal and instrumental ensembles shaped those first performances; we usually hear the passions now as the pinnacle of the choral/orchestral repertory, adapted to modern forces and conventions.

The passions were heard in Bach's time against the background of other liturgical and devotional music and of contemporary opera; listeners today tend to know little of that repertory. In their first performances they were heard as conveyers of the Gospel story and as the starting point for reflection on it; today we often listen to them as dramas, as expressions of religious sentiment, or as purely musical creations.

In Bach's time passion settings were revised, altered, and tampered with both by their composers and by other musicians who used them; today we tend to regard them as fixed texts to be treated with the respect due to Great Art. Their music was sometimes recycled from other compositions or reused itself for other purposes; we have trouble imagining the familiar material ofBach's passion settings in any other guise. And we are not even certain that we have correctly identified all of the passion repertory Bach performed: in the last i So years, one setting has gained and then lost an attribution to Bach; another is missing, but some of its music appears to be within the grasp of reconstructors.

For all their familiarity, behind Bach's passions are questions and problems caused largely by our distance from the works in time and context. This book is for people who want to know more about Johann Sebastian Bach's passion settings, about these questions and problems, and about what it means to listen to this music today. Each chapter treats a passion setting or a problem; together they cover a wide range of repertory and issues in eighteenth-century music. The essays are aimed at the general reader and assume no technical musical knowledge-two started as long program notes and one as an article in the New York Times.

The introduction explores the context of Bach's original passion performances and what it means for our listening experience today. Part I deals with much-discussed issues of Bach's performing forces and investigates how we know as much as we do about his own performances of the passions. Part II takes up individual works in performance (two by Bach and one by another composer from his working repertory), examining double-chorus scoring, the multiple versions of one composition, and the eighteenth-century practice of assembling "pastiche" passion settings by adding or substituting movements. Part III discusses music whose status in the Bach canon is in question: a lost work that might be partly reconstructable thanks to the eighteenth-century practice of reuse known as "parody," and one that might not be by Bach at all. Each chapter deals, in other words, with a compelling problem in eighteenth-century music and illustrates it through the Bach passion repertory.

The "Bach passion repertory" here means the works he composed: the St. John Passion in its several versions; the St. Matthew Passion, also known in at least two versions; and the lost St. Mark Passion. The summary in Bach's obituary famously refers to "five passions, among which one for double chorus." This has been variously interpreted, and the total may include at least one work now known to be by another cornposer and possibly multiple versions of one composition. One school of thought sees evidence of a lost passion setting by Bach from his Weimar years.

But passion settings were one of Bach's tools as a working church musician, and his shelves also held works by other composers. His passion repertory included the anonymous St. Mark Passion (widely but dubiously attributed to Reinhard Keiser) that Bach performed at least three times in different versions; the anonymous St. Luke Passion attributed at one point to Bach that he may (or may not, it turns out) have performed; and a poetic passion setting by Georg Friedrich Handel on whose music he drew.

The material draws on the latest scholarship, to which I have made some small contributions. I mention this because a lot of well-meaning writing on Bach has unfortunately not been presented from a standpoint of expertise. There is more than one hundred years of scholarship on Bach and his music drawing on primary sources; it has a lot to offer, and one of my goals is to make some of that research (including the latest findings and debates) accessible to nonspecialists. Some aspects of musical performance are matters of taste or opinion, but many come down to facts. We should aim to be as well informed as possible if we take this music seriously.

The book includes suggestions for further reading and references to some of the scholarly literature behind the ideas presented here. The most important companions to the book are recordings of the compositions themselves; I have also included suggestions of recordings that illustrate the issues discussed.

For their advice and help I am grateful to Stephen Grist, Mary Ann Hart, Michael Marissen, James Oestreich, Joshua Rifkin, Kim Robinson, students in my courses at Yale University and Indiana University, and Elizabeth B. Grist.

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

Part I Performing Forces and Their Significance

Chapter 19

Chapter 33

Part II Passions in Performance

Chapter 49

Chapter 66

Chapter 78

Part III Phantom Passions

Chapter 97

This page intentionally left blank

List of Tables

Table i-i. The liturgy for Good Friday Vespers (1:45 P.M.) in Leipzig's principal churches in J. S. Bach's era 135

Table 12. Passion repertory in J. S. Bach's possession 135

Table 1-3. Calendar ofJ. S. Bach's known passion performances in Leipzig 136

Table 2-1. Bach's 1725 vocal parts for the St. John Passion 136

Table 2-2. Bach's 1736 vocal parts for the St. Matthew Passion 137

Table 2-3. Bach's vocal parts for the anonymous St. Mark Passion 137

Table 2-4. G. P. Telemann's vocal parts for his 1758 passion 138

Table 3-1. Dialogue movements in the St. Matthew Passion 138

Table 3-2. Performing forces for the St. John and St. Matthew Passions compared 139

Table 3-3. Movements in the St. Matthew Passion 140

Table 4-1. Movements in versions of Bach's St. John Passion 143

Bach's passion settings, approaching three hundred years old, have become intimately familiar from dozens of recordings and countless performances, but today we hear them distantly removed from their original contexts. Bach wrote them for a particular liturgical event at a specific time and place; we hear them hundreds of years later, often a world away and usually in concert performances. Early eighteenthcentury conceptions of vocal and instrumental ensembles shaped those first performances; we usually hear the passions now as the pinnacle of the choral/orchestral repertory, adapted to modern forces and conventions.

Bach's passion settings, approaching three hundred years old, have become intimately familiar from dozens of recordings and countless performances, but today we hear them distantly removed from their original contexts. Bach wrote them for a particular liturgical event at a specific time and place; we hear them hundreds of years later, often a world away and usually in concert performances. Early eighteenthcentury conceptions of vocal and instrumental ensembles shaped those first performances; we usually hear the passions now as the pinnacle of the choral/orchestral repertory, adapted to modern forces and conventions.