This gem of a book sets out all that the general reader, or the singer like myself, needs to know about Handels life and works. It is clear, concise, packed with easily digestible information and full of pointers to further reading, either in books, the Internet or on the various web-sites of museums and galleries, and it gives lists of recommended recordings. The industry of the man is extraordinary I mean of Handel, but in fact Edward Blakeman has read and listened to more Handel than most of us knew existed and deserves tremendous applause for rendering down all the information he has absorbed into such accessible morsels.

I was particularly fascinated by the list of Handels operas, with the dates of their first performances and their revivals. They were really the popular music of their time, and from his golden age during the 1720s and until the 1740s, the extent of the list takes ones breath away. Then it all ceased and no Handel operas were staged anywhere in the world for nearly two-hundred years.

I realise that I was almost a pioneer of Handel opera performance in modern times. When I studied at the Royal Academy of Music, Sir Anthony Lewis, a great Handel scholar, was Principal and almost my first operatic role was in Handels Imeneo practically a first performance and Sir Anthony also conducted Handels oratorio Athalia in which I sang an aria beginning Blooming virgins, repeated three times, and causing me great problems of giggle control! As a young professional, I also sang Handel operas at the Barber Institute in Birmingham and at the Unicorn Theatre in Abingdon; both institutions had begun pioneering productions of Handel in 1959, the bicentenary of his death. And Messiah, of course, has been with me throughout my career an enduring joy. So with Edwards book as a guide, I shall look forward to discovering more of this great mans music.

Introduction

This book has grown from many years of enjoying Handels music and from one particular year of concentrated listening. I hope it may appeal to music lovers who want to embark on their own listening journey and would appreciate a few pointers on the way. Not so long ago such a journey would have been impossible: at the last major Handel anniversary in 1985, the tercentenary of his birth, most of his operas had never been recorded. Now, 250 years after his death, all are available on CD, and many may even be sampled in bite-sized chunks on the Internet (see the section on Handel online at the end of this book for some guidance on this).

I mention Handels operas in particular, because that was where I started my own listening and Im glad I did. They are absolutely central to what made Handel tick as a composer, and when you move on to any of his other works, you can hear the supreme man of the theatre still at work. But if I had been writing this book in 1908 instead of 2008, it would have been inconceivable to devote a sizeable chapter to the operas: they had been completely forgotten. A hundred years ago Handel was known largely for his oratorios and only that small selection of them that had been sanctified by the Victorians. Christopher Hogwoods biography of Handel quotes a revealing notice from The Times, reporting on a concert of Handels chamber music organised by the young Arnold Dolmetsch in 1893: Handel is known to so many people only as a composer of oratorio that there is an element of novelty in a programme which includes none but his instrumental works.

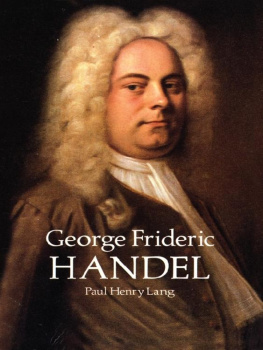

As for Handel the man, he had been effectively emasculated. Gone was any whiff of the theatre: he was seen as a religious composer who had ministered to the spiritual needs of his audiences, with a character that was correspondingly without blemish. Handels contemporaries had a much more rounded view of him, however. And so, alongside my years listening, I went back to the accounts of those who wrote about him from first-hand knowledge: men like the music historians John Hawkins and Charles Burney; the biographers John Mainwaring and William Coxe; and Handels long-time assistant, John Christopher Smith, who worked with him from 1716 onwards, joined from 1720 by his son, also (confusingly) named John Christopher Smith.

Handel had the distinction of being the first composer ever to have a biography written about him. Entitled Memoirs of the Life of the Late George Frederic Handel, it appeared in 1760, the year after his death: though published anonymously, its author was the Reverend John Mainwaring, later Professor of Divinity at Cambridge, who had worked closely with John Christopher Smith, the younger. Despite Mainwarings clerical background he knew how to tell a good story with lots of colourful detail some of it wrong, but enough right for him to remain a key primary source on Handel.

William Coxe was also a clergyman, and more significantly the stepson of John Christopher Smith, the younger. After Smith died in 1795, Coxe resolved to produce a book that would do justice both to his stepfather and to Handel. His Anecdotes of George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith was published in 1799: once again, although not correct in every detail, it is a valuable document and complements Mainwarings account.

In the mean time three other books had appeared that added significantly to knowledge both of Handels life and of his works. One was by the music historian John Hawkins, who took advantage of the many conversations he had had with Handel when writing his five-volume magnum opus published in 1775: A General History of the Science and Practice of Music devoted a large section to Handel, placing him vividly in the context of the other composers and performers of his time.

Not to be outdone, the other great music historian of the age, Charles Burney, who also knew Handel well, produced his own definitive account in 1789: A General History of Music from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Burney was particularly interested in Handel as an opera composer, studying the scores and providing a commentary on almost all of them. He had previously written A Sketch of the Life of Handel and The Character of Handel as a Composer as introductory chapters to An Account of the Musical Performances in Westminster Abbey in Commemoration of Handel, which described the series of Handel celebration concerts in 1784 and provided a commentary on the works performed.

I have quoted freely from Mainwaring, Coxe, Smith, Hawkins and Burney throughout this book and also from one of Handels female friends, Mary Delany, who merits a chapter all to herself. I have also dipped into the rich compendium of contemporary sources in Otto Deutschs Handel : a Documentary Biography, published in 1955. I hope that these eyewitness accounts will enable you to immerse yourself in the sights and sounds of Handels world while you listen to his music. The only missing element is what might have been gleaned from Handels own diary or journal (none exists), or from his letters (they are few and unrevealing). So there is always an aura of enigma surrounding him. Read on

Pocketing Handel

This book may fit into your pocket, but Handel himself wont be so easily contained. Thats one of his attractions: hes one of the most elusive, as well as one of the most intriguing, of the great composers.

It doesnt take long before you encounter various contradictions. Take his birth date, 23 February 1685. Not only does John Mainwaring, his first biographer, get the day wrong, giving it as the 24th; there was also a mix-up over old and new calendars which meant that for a long time the year was thought to be 1684. This is the year that you will see on Handels tombstone and monument in Westminster Abbey, and thus the series of grand Commemoration Concerts to celebrate the centenary of his birth took place in 1784, a whole year too early.