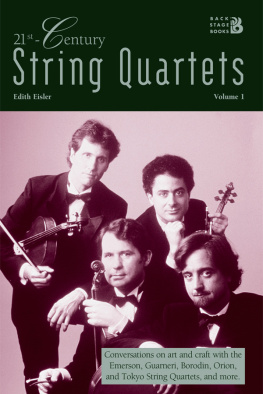

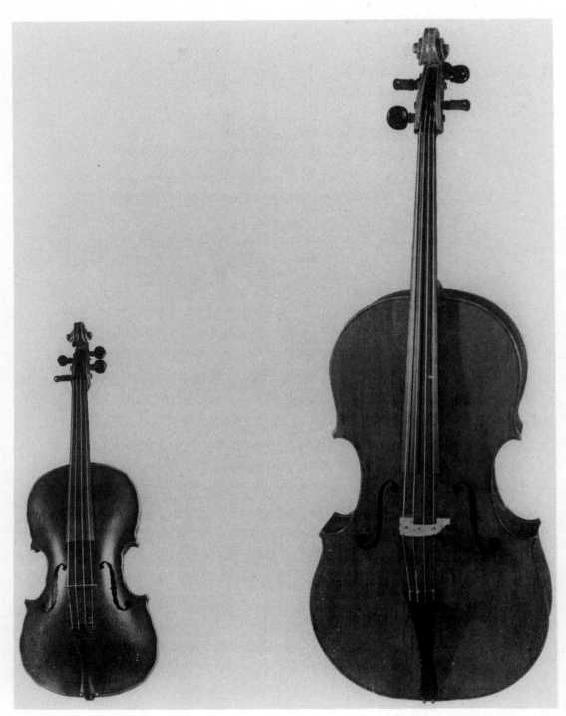

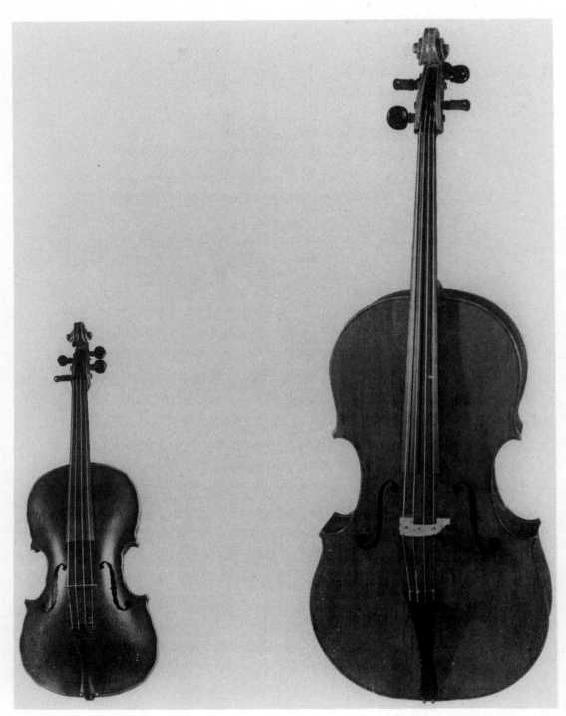

The four quartet instruments presented to Beethoven by Prince Karl Lichnowsky in i8oo. In the mid-nineteenth century the violins were said to be by Giuseppe Guarneri (1718) and Niccolo Amati (1667), the viola by Vincenzo Ruger (169o), and the cello by Andrea Guarneri (1712). More recent research suggests that these attributions were overly generous. (Reproduced by permission of the Beethoven-Archiv, Bonn.)

THE BEETHOVEN

QUARTET COMPANION

EDITED BY

ROBERT WINTER AND ROBERT MARTIN

To the memory of ourfriend and UCLA colleague Montgomery Furth.

Contents

xi

I

I

Acknowledgments

Initial steps toward the publication of this volume began with a 1984 proposal from the Sequoia String Quartet Foundation to the National Endowment for the Humanities. The proposal was funded, and a generous grant of matching funds was committed by the University of California Press. Work stretched over a period far longer than we ever imagined. We gratefully acknowledge the help of Herbert Morris and A. Donald Anderson, presidents of the Sequoia String Quartet Foundation during the relevant period; Ara Guzelimian, who wrote the grant proposal to the NEH; and Doris Kretschmer, editor at the University of California Press, who has been our partner throughout. Finally, we thank each other.

Introduction

The seventeen Beethoven string quartets are to chamber music what the plays of Shakespeare are to drama and what the self-portraits of Rembrandt are to portraiture. Our relationship with these masterworks can benefit from a companion-a vade mecum ("go with me"), as such books used to be known-for the nonspecialist, offering perspective and guidance. Such a companion should enhance the experience of listening to the quartets in live performance or on recordings. It should also enrich our understanding of the context and significance of the quartets as cultural objects.

These dual purposes-enhancing the listening experience and enriching our understanding of the cultural context-are reflected in the approach we have taken to assembling this companion. To serve the first, we asked Michael Steinberg, formerly critic of the Boston Globe and more recently Artistic Advisor of the San Francisco Symphony and the Minnesota Orchestra, to write individual essays on each of the quartets. These essays, grouped into three chapters that make up the second part of this book, succeed admirably, we believe, in providing movementby-movement guideposts for the listener. Steinberg has also contributed a glossary of musical terms that is helpful not only for his essay but for those of the other contributors as well.

The motivating concern connected with the second purpose of our companion was with the society and culture of Beethoven's time and, to some extent, the context in which the quartets are performed today. We asked for contributions from writers whom we trusted to be both original and accessible, without concern for comprehensiveness or consistency among essays. We favored interdisciplinary perspectives that reflect the diversity of approaches characteristic of the last twenty years. There is no particular order in which these essays should be read; we hope each reader will find something of interest to begin with and that the threads of connection will lead to the other essays.

Joseph Kerman's essay, "Beethoven Quartet Audiences: Actual, Potential, Ideal," examines in detail one aspect of the reception history of the quartets: to what changing audiences did Beethoven address these works? This apparently simple question opens complex and fascinating issues. For example, Kerman develops a connection between the arthistorical notion of "absorption," developed by Michael Fried in connection with certain eighteenth-century painters ("the supreme fiction of the beholder's nonexistence"), and the fact that in certain of Beethoven's late quartets "the sense of audience superfluity is almost palpable."

Robert Winter's essay, "Performing the Beethoven Quartets in Their First Century," brings together information on how and under what circumstances the quartets were performed before the era of sound recordings. We learn of the extent of French influence on those who first performed the quartets and of their mix of partly modern, partly oldfashioned instruments. Through the eyes of three popular nineteenthcentury German and American music periodicals, Winter examines the often surprising manner in which the nineteenth century viewed and consumed the quartets. For example, until well after mid-century, string quartet ensembles consisted most frequently of either family groupings or of the principal players from permanent orchestras who came together for a handful of concerts each year.

Maynard Solomon opens his essay by pointing out that nineteenthcentury musicians and critics viewed Beethoven as the originator of the romantic movement in music; indeed he was lifted to mystical status as a romantic paradigm. Beginning with the work of the German scholar Arnold Schmitz in the 192os and culminating in the influential work of Charles Rosen in the 197os and i98os, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction, transforming Beethoven into the archetypal classicist. The question, Solomon argues, is not simply how Beethoven should be viewed by historians of culture but how his music is to be heard: the issue "has an important bearing on whether we perceive and perform works such as the quartets primarily as outgrowths of eighteenth-century traditions and performance practices or as auguries of fresh traditions in the process of formation."

Leon Botstein-social historian, conductor, and college president has contributed a wide-ranging essay that places the quartets in the context of Viennese society, philosophy, theater, and literature. Connections to other essays in this volume emerge at every turn; there is discussion of the context of the earliest performances (Winter), of the special relationship of audience to chamber music performance (Kerman), of the reception of the quartets and views as to their "place" within the musical scene (Solomon); there is even discussion, in connection with the twentieth-century Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, of expression and meaning in the quartets that intersects with Robert Martin's discussion of performance and interpretation.

Drawing on his experience as cellist of the Sequoia String Quartet, Robert Martin looks at the quartets from the perspective of the performer, asking what sorts of interpretive decisions are made and on what basis. Martin takes advantage of the circumstance that in chamber music, rather more than in solo or orchestral playing, players are led to verbalize their reasons for musical decisions in order to persuade their colleagues. Martin asks about the relationship between performers, composer, and score; he examines a literalist, a "buried treasure," and a textual interpretation of this relationship before settling on what he calls a collaborative view.