The Life and Times of Chaucer

John Gardner

Contents

ONE

Chaucers Ancestry and Some Remarks on Fourteenth-Century English History

TWO

Chaucers Youth and Early EducationLife and the Specter of Death on the Ringing Isle (c. 1340-1357)

THREE

Chaucer as Young Courtier, Soldier, and, in Some Sense, Lover (1357-1360)

FOUR

Chaucers Further Education, a Summary of Some Fourteenth-Century Ideas of Great Importance to Chaucer, and the Poets Marriage to Philippa RoetSpeculations and Scurrilous Gossip (1360-1367)

FIVE

Significant Moments and Influences: Pedro the Cruel, Two Deaths, that Shameless Woman and Wanton Harlot Alice Perrers, and Italian Artistic Humanism (1367-1373)

SIX

Chaucers Adventures as Celebrated Poet, Civil Servant, and Diplomat in the Declining Years of King Edward III (1374-1377), with Some Remarks on Chaucers Honesty and Comments on his Art

SEVEN

Life During the Minority of Richard IIThe Peasants Revolt and Its Aftermath (1377-c. 1385), with More Scurrilous Gossip

EIGHT

The Rise of Gloucester and Chaucers Fortunes as a Royalist in Evil Times (c. 1385-1389)

NINE

The Deaths of Gloucester, John of Gaunt, and the Hero of this Book

APPENDIX

The Pronunciation of Chaucers Middle English

I HAVE BEEN HELPED BY INNUMERABLE PEOPLE ON THIS BOOK, including all of my Chaucer students over the past twenty years and various university friends and colleagues, especially Donald Howard and Russell Peck, who read versions of this manuscript and helped me avoid many errors. Southern Illinois University at Carbondale has given me grants and time off, year after year, for work on this project, and helped provide research and secretarial assistance, especially Sandra McKimmey, whose long hours helping me on this and other books are beyond the appreciation of words. I also owe thanks to Alan Cohn, Humanities Librarian at Southern Illinois, who has helped me locate and get hold of books and articles I could not have gotten without him; and to E. L. Epstein, who has for ten years patiently listened to my ideas and has sometimes published some of them for me in his magazine Language and Style. And I thank the Houghton Mifflin Company for permission to quote from F. N. Robinsons second edition of The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. (I have sometimes simplified Robinsons punctuation and spelling, and Ive added aids to pronunciation and the interpretation of hard words.) Above all, in a way, I owe thanks to my former teacher John C. McGalliard, in whose Chaucer class, long ago, all this started.

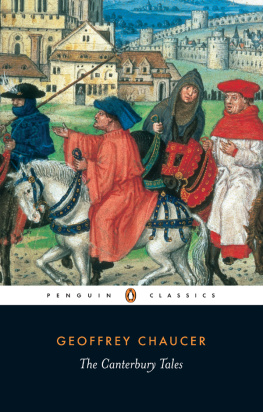

NO POET IN THE WHOLE English literary tradition, not even Shakespeare, is more appealing, either as a man or as an artist, than Geoffrey Chaucer, or more worthy of biography; and no biography, it seems at first glance, should be easier to write. Despite the complexity of the philosophical systems and social mores that shaped his thought, Chaucers general way of looking at things seems clear as an English April day; and since he worked for the government, which kept elaborate records, we have numerous facts to pin his life to. Yet telling his story proves more difficult than one might think. In his poetry, Chaucer does not talk about himself, except jokingly and trivially. He nowhere tells us in explicit fashion what he thought about particular acquaintances, or even how he felt when his wife died. And the official facts of Chaucers life, numerous as they are, are frequently lures toward befuddlement, not so much because the poet and his times are mysteriousthough they are, and especially so for Americans, to whom the English gentrys titles are as confusing as the names in War and Peaceas because, like the missing parts of old frescoes, the vital connectionsthat is, Chaucers private feelings and the emotional pressures that gave shape to his ageare for the most part lost utterly, vanished from the world like smoke. However one may pore over the hints and clues in the official records of the fourteenth century, the traditional conjectures about Chaucers life nearly all remain conjectures and the facts mere facts.

That should hardly surprise us. We can barely understand ourselves, these days; barely piece together our own biographies, though for those we have something like complete information. Since nothing remains of that once wise and gentle, much loved old man (as all his contemporaries were quick to agree)or nothing but some dry and confusing records, some beautiful, ironic, and ambiguous poetry, two or three pictures, and some bones whose measurements inform us that, if theyre really Chaucers, he was five foot six (about average at the time)we have no choice but to make up Chaucers life as if his story were a novel, by the play of fancy on the lost worlds dust and scrapings. So Chaucer himself made up the classical age, dressed up young Troilus in crusaders armor and decorated legendary Theseus Athens with battlemented towers, wide jousting grounds, and sunny English gardens. This does not mean, of course, that a biographer has license to be cavalier about historical detail, or exclude possible interpretations of the facts out of preference for others that make livelier fiction. But while I try in this book to be careful about facts, my purpose is not academic history, but rather something between that and poetic celebration of things unchangeable. Human history, it seems to me, never repeats itself and can never be recaptured; but human emotions endure like granite, for instance the lust of old men for young girls, or the imprisoned wifes restlessness, or the anger of the scorned homosexualChaucers subjects. The age-old human emotions live on and on, generation after generation, and the best poets feel them or spy them out in others and cunningly transfix them; and wondering about that, wondering about when and where the poet perhaps experienced the emotion he describessince no one will ever know the answer for sureis as much the business of the novelist as that of the historian. For all the history I include in this book, I am no historian but a novelist and poet, a literary disciple come centuries late. I include mere moments of historical background, dull lightning flashes that reveal in frozen gesture events whose developmentin comparison to the story of any single human lifewere as lumbering and awesome as the shifting of continents on Earths vast skin. I make no pretense of explaining or even connecting such movements. I mean only to convey my own impression of how they affect, subtly yet profoundly, ones subjective image of the hero of this book.

What kind of man was Geoffrey Chaucer? One begins on the answer with easy confidence, but almost immediately one finds oneself faltering, hunting through the poetry in increasing dismay, and beginning to equivocate, to bluff.

What Bach and Beethoven are to music, Chaucer and Shakespeare are to English poetry. For all the calm of his familiar portrait, Shakespeare was a towering Romantic genius, a man who, like Beethoven, seemed to know everything about human emotion and to flinch from none of it, building plays not out of dramatic theory but by the impetus inherent in conflicting passions, a poet willing to take any aesthetic risk. Chaucer, on the other hand, was a sort of medieval, well-tempered Bach (Bach himself was, at least on occasion, an inkpot thrower), an artist-philosopher more tranquil and abstract, more conservative and formal than any poet of the Renaissance. Though a difficult poet, he presented himself as a nave and merry storyteller, an avoider of the dark spots in human experience, a sedulous and tactful entertainer of princes. Though a devastating mimic when he turned his acquaintances into characters in poems, he remained, even at his most satiric, a devoted servant and celebrator of the orderly, God-filled universe revealed in the

Next page