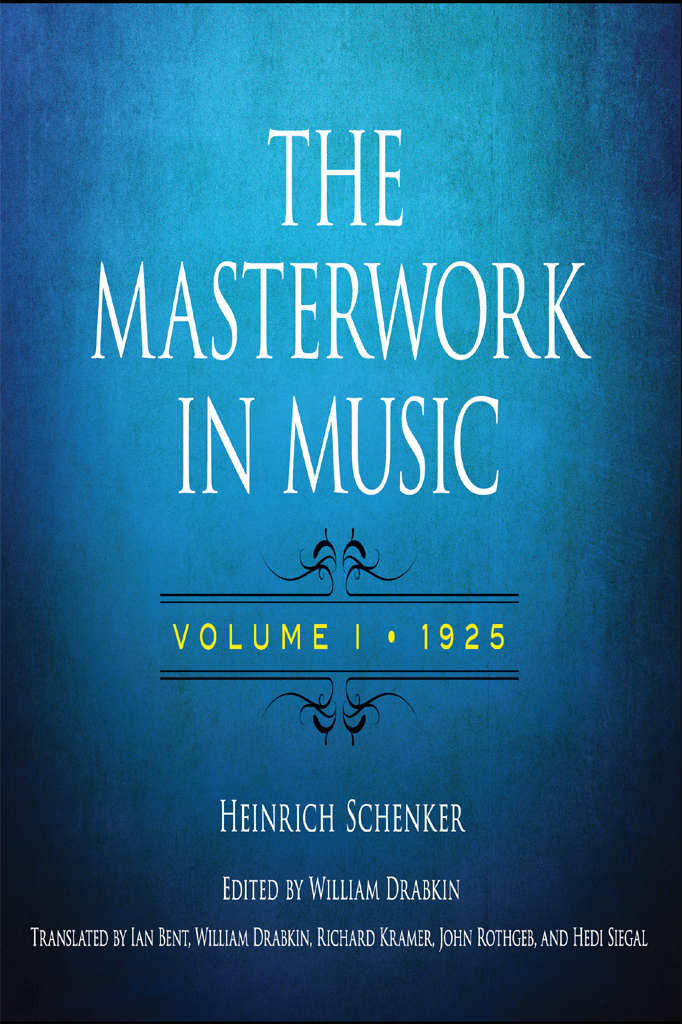

THE MASTERWORK IN MUSIC

VOLUME I 1925

H EINRICH S CHENKER

Edited by

W ILLIAM D RABKIN

Translated by

I AN B ENT , W ILLIAM D RABKIN , R ICHARD K RAMER, J OHN R OTHGEB , H EDI S IEGEL

D OVER P UBLICATIONS , I NC .

M INEOLA , N EW Y ORK

Heinrich Schenker (18681935) was one of the leading music theorists of the twentieth century. The Masterwork in Music was written in three volumes between 1925 and 1930 and is distinguished from earlier writings by its depth of vision, demonstrated both graphically and verbally. Although the concept of structural hierarchy is already present in Der Tonwille (19214), it becomes more prominent in Das Meisterwerk.

Volume I of this work is translated here by a team of distinguished theorists. It includes analyses of keyboard works by Bach, Scarlatti, Chopin, Beethoven and Handel and solo violin music by Bach, as well as more general essays on aspects of theory, analysis and performance.

Long awaited in English translation, this edition will also be invaluable to scholars for the editorial annotations and elucidations provided by Dr Drabkin and his translators.

Copyright

Copyright 2014 by Dover Publications, Inc.

Introduction copyright 2014 by William Drabkin

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2014, is an unabridged republication of the first English translation of the work, originally published by Cambridge University Press in 1994. The work was originally published in German as Das Meisterwerk in der Musik, by Drei Masken Verlag, in 1925. William Drabkin has prepared a new introduction specially for this Dover edition.

International Standard Book Number

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-79935-3

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

78002301 2014

www.doverpublications.com

DAS MEISTERWERK IN DER MUSIK

A BRIEF PUBLISHING HISTORY

The path leading to the three volumes of The Masterwork in Music began in 1910, when Schenker proposed to his then publisher, J. G. Cotta of Stuttgart, a Handbibliothek (library of handbooks) devoted to individual works, as a validation of his evolving theory of music and, at the same time, an accessible account of popular concert pieces. Years later, this plan was to be realisedwith a new publisher, Universal Editionas a series of pamphlets on a variety of musical topics. Der Tonwille, which ran to ten issues from 1921 to 1924, was intended to make concise accounts of individual workstheir structure, textual issues, remarks on performance, and surveys of the literatureavailable to music students and concert-goers. But the earliest issues already created friction between author and publisher; Emil Hertzka, the director of UE, refused to allow the companys name to appear on the cover of Tonwille, and he later sought to suppress Schenkers inflammatory polemics, much of which was in direct conflict with UEs modernist agenda. Schenkers difficulties with Hertzka, whom he was to brand a censor and later a terrorist, arose even as the first issue of Tonwille was going to press; they persisted throughout the early 1920s and were settled only by the intervention of legal counsel on both sides.

Even as Hertzka was seeking ways of resolving their differences, Schenker was in search of a new publisher to continue the Tonwille series. His former pupil Otto Vrieslander, based in Munich, had recently published a book on C. P. E. Bach and an edition of his songs with two of the citys publishing houses, R. Piper and Drei Masken Verlag respectively. Vrieslander put Schenker in touch with Alfred Einstein, the music editor at DMV, and by November 1924 the two men were in correspondence over the continuation of the Tonwille project under a new name and in a new format. Instead of a succession of 32-page booklets, of which Universal were prepared to publish at most four per year, Einstein offered Schenker a single, annual publication comprising up to 15 bogen (large sheets, folded into gatherings of 16 pages). DMVs own Mozart-Jahrbuch was to serve as a model, and Schenker signed a contract that committed him to putting together a yearbook of analytical essays by 1 July, with publication coming towards the end of the year.

Masterwork I

Full of enthusiasm, but not a little concerned about the magnitude of the task that lay ahead, Schenker worked at a feverish pace to get the first yearbook ready before the summer holiday. His diary records that his wife Jeanette finished the final handwritten draft of the text on 12 June and that it was posted two days later. (It also records that Schenker was already at work on an essay for Master-work II the counter-example on Regers Bach Variationsin the days before their departure for Galtr in the Tyrol on the 26th.)

In spite of this new momentum, the publication of Masterwork I was held up for many months. DMV were still searching for a suitable printing house in the autumn (they eventually settled on the Viennese firm of Waldheim-Eberle), and further delaysand expensewere incurred in the manufacturing and use of the special typographical symbols that were now current in Schenkers analytical writing. Correcting the proofs also proved to be time-consuming and costly.

Although it was to prove impossible to publish the first book by the end of the year, the publishers agreed to backdate the volume. Thus Masterwork I bears the date of 1925, even though it was still at the bindery in early June 1926. As he noted in his diary (11 June 1926), Schenker received his first complimentary copies on the very day that he and Jeanette dropped off the manuscript of Masterwork II to the Vienna office of DMV.

Masterwork II

Receipt of the manuscript of the new yearbook was duly acknowledged by the Munich office of DMV on June 21st. Rather than greeting the new work with enthusiasm, however, the publishers presented Schenker with a bill of 350 marks for correction costs for Masterwork I and warned him that they would not proceed with production of a second volume until they had some way of gauging the sales of the first. To this news, Schenker responded with outrage, and the threat of legal action for breach of contract, pointing out that (1) he had punctually fulfilled his obligations to produceby superhuman efforta complete manuscript by the agreed deadline; (2) he had planned his yearbooks with a view to their appearance in a series, not as one-off publications; and (3) had the submission of a second Masterwork not been welcome, he would at the very least have expected the publishers to have informed him of this much sooner, not a year after he had commenced work on it. After receiving a further, more conciliatory letter from DMV the following month, Schenker agreed to defer a decision until the autumn. But even by late November, an offer to begin production of the second yearbook still had not been received.

At this point, the Vienna-based musicologist Otto Erich Deutsch offered to represent Schenkers interests in the matter. Deutsch knew Einstein at DMV, but his association with Schenker dated back from before the war, and the two had collaborated amicably on a facsimile edition of the Moonlight Sonata autograph and sketches in 192021. Schenker and Deutsch met frequently to discuss matters relating to musical sources. Deutsch had in the meantime become the private librarian of Anthony van Hoboken, a wealthy Dutch collector of first editions of music and books on music, who began studying piano and theory with Schenker in 1925.