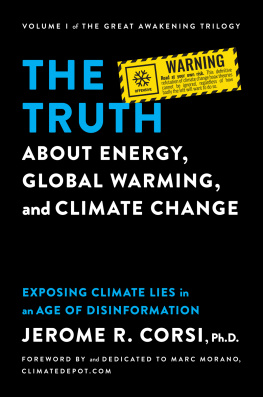

This book is dedicated to Richard Lindzen, Fred Singer,

Steve McIntyre, Anthony Watts, Bob Carter, Henrik Svensmark,

Nir Shaviv, Syun-ichi Akasofu and all those who have valiantly

fought to uphold the principles and disciplines of true scientific

inquiry through a time when so many lost sight of them.

Contents

Chapter 1: How it all began

Cooling and warming: 19721987

Chapter 2: The road TO Rio

Enter the IPCC and Dr Hansen: 19881992

Chapter 3: The road to Kyoto

Enter Vice-President Gore and IPCC 2

Chapter 4: The hottest year ever

Enter the Hockey Stick and IPCC 3: 19982003

Chapter 5: The political temperature rises

A far greater threat than terrorism: 20042005

Chapter 6: Hysteria reaches its height

Gore and the EU unite to save the planet: 20062007

Chapter 7: The temperature drops

IPCC 4, The modellers lose the plot: 2007

Chapter 8: A tale of two planets

Fiction versus truth: 2008

Chapter 9: Countdown to Copenhagen

Colliding with reality: 2009

To capture the public imagination we have to offer up some scary scenarios, make simplified dramatic statements and little mention of any doubts one might have. Each of us has to strike the right balance between being effective and being honest.

Dr Stephen Schneider, Discover, October 1989

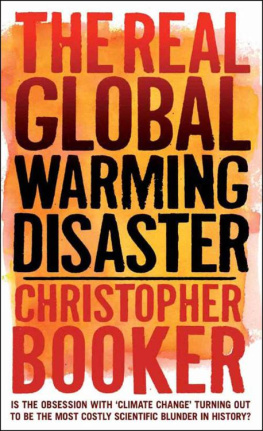

As the first decade of the twenty-first century nears its end, there is ever more evidence to suggest that, thanks to global warming, the world may be heading towards an unprecedented catastrophe. But it is not the one which has been so widely and noisily predicted by the likes of Nobel Peace Prize winner Al Gore.

The real disaster to be brought about by global warming, it now seems highly possible, is not the technicolor apocalypse promised by Gore and his many allies melting ice sheets, rising sea levels, hurricanes, droughts, mass-extinctions. It will be the result of all those measures being proposed by the worlds politicians in the hope that they can avert a nightmare scenario which, as many experts now believe, was never going to materialise anyway.

This book tells the story of what has been, scientifically and politically, one of the strangest episodes of our time. Indeed, as a case study in collective human psychology, it is turning out to have been one of the most extraordinary chapters in the history of our species. In the closing decades of the twentieth century a number of scientists became convinced that the earths atmosphere had suddenly begun to heat up to an extent never known before, and that this was caused by the activities of man. The emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuels was now trapping the suns heat to such an extent that the balance of nature had become dangerously disturbed.

Having created elaborate computer models which seemed to confirm their dire predictions, in a remarkably short time these scientists vociferously urged on by environmental activists and the media convinced key political figures, most notably the then-Senator Al Gore, that this rise in temperature was easily the most urgent challenge confronting the human race. Only by taking the most drastic action might it be possible for disaster to be averted.

The chief driver in promoting this cause was an organisation set up by the United Nations in 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contrary to general supposition, the IPCC was essentially not a scientific but a political body. Although its findings would commonly be described by politicians and the media as representing a consensus of the views of the worlds top climate scientists, the vast majority of its contributors were not climate experts and a great many were not scientists at all.

The IPCCs brief was not to weigh the evidence for whether or not man-made global warming was taking place. It was to take human-induced climate change as a given, to assess its likely impact and to advise on what should be done about it. Working to an agenda tightly controlled from the top, the IPCCs role was thus not to question the new orthodoxy but to promote it, and to inspire the political response to a threat the nature of which was assumed from the outset. By 1997 this had led to the signing by 180 countries of the treaty known as the Kyoto Protocol, many of them to reduce CO2 emissions way below their existing levels.

By the early years of the twenty-first century governments were adopting an ever more ambitious series of policies, intended not just to meet those Kyoto targets but to go far beyond them. The bill for these measures, if all were put into effect, would be astronomic, making them by far the most expensive set of proposals ever put forward by any group of politicians in history. This would eventually necessitate such a dramatic change in the way of life of billions of people that it was hard to imagine how modern industrial civilisation could survive in any recognisable form.

As the first decade of the new century neared its end, however, just when governments had begun to implement these measures, the scenario began dramatically to change. Although CO2 levels in the atmosphere were still steadily rising, it became obvious that the earths temperatures were no longer following suit, as the IPCCs consensus dictated they should. Far from continuing to hurtle inexorably upwards, the temperature curve had flattened out and was even dropping, in a way none of those officially approved computer models had predicted.

At much the same time, it emerged that the supposed scientific consensus was nothing like so unanimous as the politicians and the media had been led to believe. By no means all the worlds scientists were agreed even that the temperature rise towards the end of the twentieth century was unprecedented. An increasing number doubted that it had been caused by the rise in carbon dioxide levels.

With growing force, ever more climatologists and other experts were now showing that the evidence for a human link to such warming as had occurred had been not just seriously exaggerated but even deliberately manipulated, to produce findings which the data simply did not justify. They were also coming up with alternative theories as to what was shaping the worlds climate which fitted the observed data much more plausibly.

Then in the autumn of 2008 the global economy was suddenly plunged into its deepest recession for more than 70 years. With the time approaching for agreement on a successor to the Kyoto Protocol, political attitudes towards global warming began to polarise.

On one hand, the majority of Western politicians, led by the new US President Barack Obama, were still locked into their belief that the IPCCs orthodoxy was correct, and that all those astronomically costly measures were still urgently necessary. Others began to argue that the immense economic sacrifices these would involve made them no longer affordable. Developing countries such as China and India continued to insist that, if they were expected to cut back on their carbon emissions, the bill for this must be picked up by those developed countries which in their view had created the problem in the first place, and whose economies were now in crisis.

The political consensus was beginning to crack apart just as the scientific consensus had done. Had the story of the panic over global warming reached a critical turning point? If the momentum towards committing mankind to all those steps designed to fight climate change now seemed unstoppable, might it turn out to have been the most reckless and costly political gamble in history?