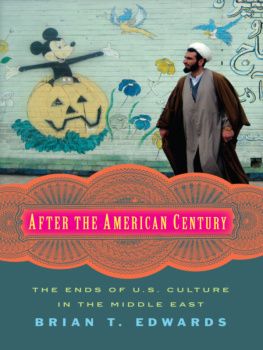

AFTER THE AMERICAN CENTURY

BRIAN T. EDWARDS

AFTER THE

AMERICAN CENTURY

The Ends of U.S. Culture in the Middle East

Columbia University Press / New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54032-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Edwards, Brian T., 1968

After the American century : the ends of U.S. culture in the Middle East / Brian T. Edwards.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-17400-8 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-54055-1 (e-book)

1. United StatesRelationsMiddle East. 2. Middle EastRelationsUnited States. 3. Popular cultureUnited States. 4. Popular cultureMiddle East. 5. OrientalismUnited States. 6. Ethnic attitudesMiddle East. 7. Culture diffusionMiddle East. 8. GlobalizationSocial aspectsMiddle East. 9. Middle EastCivilization21st century. I. Title.

DS63.2.U5E38 2016

303.48256073dc23

2015020790

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

COVER IMAGE: Mural in Isfahan, Iran, advertising a local fruit-and-vegetable market. (Photograph by Brian Edwards)

COVER DESIGN: Archie Ferguson

References to Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For Kate Baldwin

and for our children

Oliver, Pia, Theo, and Charlotte

Neitherhad asked her why, but she thinks now that if they had she might have told them she was weeping for her century, though whether the one past or the one present she doesnt know.

William Gibson, Pattern Recognition

CONTENTS

W HEN I FIRST started this project in 2005, I expected that Beirut would be one of the principal sites of my research and get its own chapter. I have since traveled to Lebanons capital seven times. For about a year, I engaged a research assistant in Beirut, whom I asked to track when and how American cultural artifacts appeared in Lebanese media, including book and film reviews, popular culture, and online postings. I didnt quite know what I was looking for, though we gathered a great deal of interesting material. The amount was quickly overwhelming. And then Beirut was under attack by Israel again, and such a project seemed incidental if not impracticable.

On one of those trips to Beirut, I happened across a little caf called Caf Younes. The branch in Hamra is well known to those who live in or travel to the city, around the corner from the famous Commodore hotel, where Western journalists were based during the Lebanese civil war of the 1990s. It remains a place I visit on each trip.

At first glance, this location gave off a certain air of authenticity. Seventy years earlier, in 1935, Amin Younes had returned to Lebanon from Brazil to open a coffee shop in downtown Beirut (the branch in Hamra opened in 1960 and was the second). When I visited, a man named Abou Anwar was celebrating a half-century as roaster. He had worked for Younes since 1955, when he was sixteen years old.

To be sure, multiple traditions and styles of coffee preparation were in evidence here, a palimpsest left behind by the numerous imperial powers with an interest in Beirut. At Younes, you could have Turkish coffee made to order or excellent espresso or caf crme from the traditions learned during the French Mandate period. American-style filtered coffee, too, was on the menu.

My first visit to Caf Younes came five years after a big Starbucks had opened on Hamra Street, just a few blocks away. In news coverage about the massive expansion of Starbucks in those years, journalists worried that the great caf culture of the Arab Middle East would be lost orworseAmericanized by the huge Seattle chain. Language similar to that which greeted the arrival of McDonalds in Moscow and Beijing during the previous decade was reemerging.

I myself wondered how a Starbucks around the corner would affect Caf Younes. How could this place compete with the trademark frappuccinos, to say nothing of the spacious seating area, plush chairs, and sidewalk terrace, none of which Younes had here?

Posted on the wall were news clippings from the local press. There I found my answer. Amin Younes, the founders thirty-something grandson, had been asked precisely the same question that was on my mind. He answered in a way that surprised me: the arrival of Starbucks had the potential to improve his business. Starbucks was changing how his own customers thought about coffee drinks and in turn provided him with the opportunity to expand his menu. As Younes told a journalist, When Star-bucks opened, we had fewer than 10 varieties of coffee drinks on offer. Weeks later, we had expanded the selection to more than 20, and sales were higher.

Though I decided not to pursue research in Beirut for this book, Youness comment stuck with me. In the face of a challenge that others (myself included) assumed would wipe out his business, Youness response represented not only business acumenthe recognition that Starbucks was helping him expand his own menubut also a form of creativity. Younes took the American menu and, rather than replicating it, made it into one his own customers would cherish, responding to their own now altered sense of what a caf might serve. There were the typical espresso drinks, but now he added drinks with Middle Eastern flavors and spices, such as a cardamom-flavored espresso, lattes laced with rose water, and smoothies that incorporated green bananas and mango.

On my most recent visit to Beirut in February 2015, I visited not only the small location in which I had first sat in 2005 but also the new, large-scale addition next door, complete with souvenirs, books, customized mugs, and T-shirts. Though there were now comfortable seating and a sidewalk terrace, the place was no replica of Starbucks but had retained its own personality. Caf Younes had done well.

A few months earlier, in May 2014, as I was completing the manuscript of this book, the Middle East and North African Studies Program at Northwestern hosted the Tangier filmmaker Moumen Smihi. Smihis visit was in connection with a film retrospective organized in Santa Cruz that we had brought to Evanston. Though I was working on this book when he came, I assumed Smihi was working in a different paradigm than the younger Moroccan filmmakers I discuss in . After all, Smihiborn in 1945 and a former student of Roland Bartheswas more influenced by structuralist theory, I assumed, than by digital culture.

After one of his talks, I asked Smihi what he thought about what anthropologist Kevin Dwyer has called the paradox of Moroccan cinema, wherein the movie houses are closing even as a dynamic series of films is emerging from Morocco. The curator of the retrospective had gone to considerable expense to procure and screen 35-millimeter prints of Smihis lush films, which were otherwise out of circulation.

Smihi responded to my question in a way that surprised me: Actually, he said, this crisis of [movie] theaters in Morocco is my chance. By chance, he meant the French sense of the word, my good luck. He went on to say, Its the distributors who decide how many [in the] audience they must have, and then [the distributors dont] take films below a certain number. He paused. I reflected on how little known Smihi himself was in the United States precisely because of this dynamic. But then, again, he surprised me.