The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

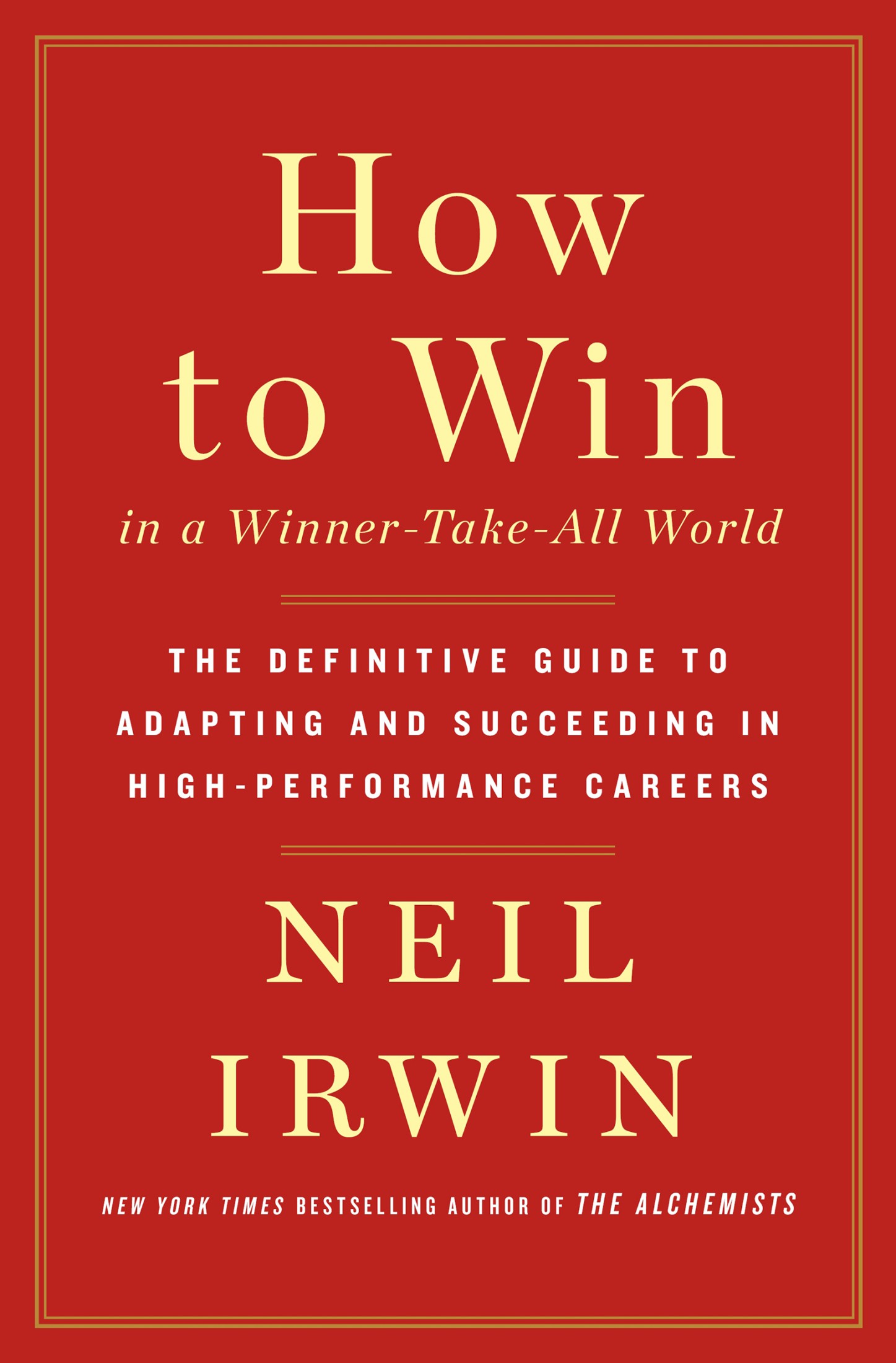

The Wind and the Current

THE NEW ECONOMICS OF

CAREER MANAGEMENT

I was twenty-two years old and fresh out of college when I started my first job at The Washington Post. My job description in those days was to report and write about local companies. But its more accurate to say that I was simply a worker at one end of a long assembly line.

After I finished writing an articlesay, four hundred words with a boring headline like CyberCash to Unload Assets for $20 Millionit would be launched on a step-by-step process that was repeated hundreds of times each day. First my editor would revise my draft to try to make it better. Then it would go to the copy desk, where another editor would make sure it complied with the papers Byzantine style rules; God forbid I ever mention a company without spelling out its full legal name and noting the town in which its headquarters was located. Then a couple more editors would give it yet another look, before passing it along to the prepress department, whose role in the process I never totally understood. After that, it was printed and the resultant paper folded, bound into tiny packages, moved to trucks, and finally dropped off with individual delivery drivers who would deposit it on hundreds of thousands of doorsteps in the Washington metropolitan area.

Careers in those days were equally linear. If a writer did a good job, he or she might be promoted to become an editor overseeing a few people, and then an editor overseeing a lot of people. Many of my colleagues had done the exact same job for years, even decades. Those who were ambitious knew exactly how to channel that ambition.

Even if you werent able to snag a job at The Washington Post or my current employer, The New York Times, it wasnt a big deal, because dozens of newspapers in other big cities offered career opportunities and compensation that were nearly as good. The technology of print newspapers created local monopolies that allowed at least one big paper in each city of any size to be highly profitable and offer many good jobs. In career terms, there just wasnt that big a gap between, say, The Philadelphia Inquirer or The Baltimore Sun and the Times or the Post.

What I didnt know at the time was that the economics of our industry were about to change, with radical implications for people like me trying to make a career in it. If you visit the Post or the Times today, you will find not a single giant assembly line in which reporters feed articles into the newspaper, but rather teams of people with a myriad of skills creating not just newspapers but a range of productsaddictive podcasts, apps optimized for mobile devices, and immersive virtual reality experiences, to name only a few.

As youd imagine, this has upended what it takes to have a successful career in the media industry. When the underpinnings of a business are in flux, and the best work is done by teams of people with dramatically different skillsa team might include software engineers, graphic artists, data scientists, and video editors, along with writersit is no longer so obvious what people should do to ensure they will remain employed, let alone get ahead.

The gap between the top handful of publications and the next tier has widened, both in terms of the number of jobs available and how well they pay. In digital media, the handful of organizations with the very best products and technology reach readers around the planet, while the old local print monopolies are no more. Consequently, if you want to sustain an upper-middle-class life as an investigative reporter or foreign correspondent, opportunities are fantastic at places such as the Times or Post or Wall Street Journalthe top handful of organizations with global reachand brutal if you are in a second-tier organization.

And long gone is the old pattern in which people who got hired at a leading media outlet could expect to remain employed there for decades doing mostly the same job. Those who do stay with an employer for a long time tend to do so by adjusting to changing strategies and ways of working; those who fail to adjust are likely to find themselves laid off.

Ive had to pay close attention to these changes in my industry for existential reasons. But the more Ive spoken with people in other industries, the more Ive been struck that people who seek a well-paying, professional-track career in nearly every sector are grappling with the same challenges: reinvention of business models due to digital technology; the rise of a handful of successful superstar firms; and rapidly changing understandings around loyalty and the level of mutual commitment to the employee-employer relationship.

In manufacturing and retail, banking and law, health care and education, and certainly all corners of the software business and the rest of the tech universe, what it means to do a job well and have a successful career is changing faster than most peoples understanding of how to navigate it. This has made the workplace seem scarier, particularly to midcareer people who suddenly find that their parents advice (show up early, work hard, learn your craft) is no longer enough.

But, as importantly, it has conferred an advantagea significant advantageon those strategic enough to shift their approach.

THE SURVIVORS CODE

Most of the people I worked with when I joined the Post are long gone from the industry, many having fallen victim to waves of buyouts and layoffs that took place as the internet upended the economics of our business.

But some have had tremendously successful careers beyond the imagination of the average reporter only a couple of decades ago. You may have heard of a few of them. Mike Allen and Jim VandeHei were White House correspondents, attending press conferences and speeches and dutifully reporting what they heard, when I was a young business writer. But in 2007 they surprised all of us by starting Politico and then a decade later Axios; both ventures have been leaders in reinventing the media industry for the digital age. Michael Barbaro, a young fellow writer on the Post business desk back when I was starting out, is now managing editor and host of The Daily, a wildly popular podcast from The New York Times; he has helped pioneer a new form of storytelling that has helped millions of people understand the world better. Kara Swisher had left the department a couple of years before I arrived; she would go on to be not just the leading tech journalist of our time, at The Wall Street Journal and then as founder of Recode, but an innovator in building a media business model reliant on live events.

Beyond those notable names are hundreds of people behind the scenes whose careers have thrived in the digital era, doing jobs that would be unrecognizable to their younger selves. Copy editors used to do comparatively rote work fixing typos and applying style rules; they had a reputation for being crusty introverts. Those who have thriving careers now are, in effect, digital strategists. They try to figure out how to package each article in ways that will maximize its chance of finding an audience. They select visuals, predict what web address is most likely to appeal to algorithmic search engines, craft social media copy, and collaborate with writers, graphic artists, and others to come up with the most engaging possible headline.