1. Introduction

There are two primary choices in life: to accept conditions as they exist, or accept the responsibility for changing them .

Denis Waitley

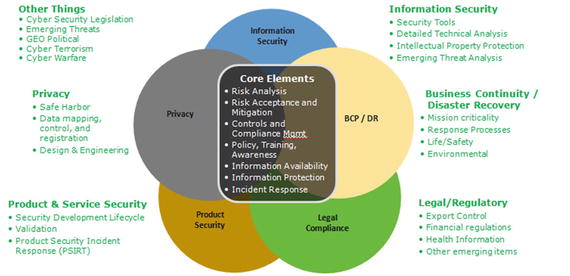

In January 2002, I was hired to run a new Intel internal program called Security and Business Continuity. The program had been created following the major security events of the previous year (9/11 and the Code Red/Nimda viruses) and it focused primarily on the availability risks at that time. I had no background in technical security, but I had been at Intel for nearly 10 years in a variety of business-related positions, mostly in finance. As I learned about information risk during the first few months, it became apparent to me that the world was starting to change rapidly and that a perfect storm of risk was beginning to brew. In June 2002, I put together a diagram (Figure ) to explain the risks to my manager, Intels CIO, and anyone who would listen to me. The diagram has been updated slightly since then to more explicitly highlight the geo-political forces that are a key part of the threat, vulnerability, and regulatory risk landscape.

Figure 1-1.

The perfect storm of information risk

Today, it is clear that my view of the world was essentially accurate. Security breaches and intrusions are reported almost daily at organizations of all sizes, legal and regulatory issues related to technology use continue to grow, and geo-politics have surged to the forefront of some of these discussions in a post-Snowden era. Cyber attacks and data breaches are now considered the biggest threats to business continuity, according to a recent survey (Business Continuity Institute 2016).

But the key question that I asked in the first edition of this book is still valid. Is information security really effective? Given the rapid evolution of new technologies and uses, does the information security group even need to exist?

Obviously, this is a somewhat rhetorical question. I cannot imagine that any sizeable organization would operate well without an information security function. But the real issue is whether the information security group should continue to exist as it does today, with its traditional mission and vision . It is clear from the prevalence of breaches and compromises that we have not kept up with the threats, and we appear to be slipping farther behind as the world grows more volatile, uncertain, and ambiguous. It is no wonder that we have fallen behind: as the world of technology expands exponentially, so do the technology-related threats and vulnerabilities, yet our ability to manage those security and privacy risks has progressed only at a linear rate. As a result, there is a widening gap between the risks and the controls. In fact, many organizations have essentially given up actively trying to prevent compromises and have defaulted to reliance on after-the-fact detection and response tools.

As information risk and security professionals, we should be asking ourselves pointed questions if we wish to remain valuable and relevant to our organizations. Why do we exist? What should our role be? How are new consumer and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies shaping what we do, and can we shape the world of these new technologies and usage models? How is the evolving threat landscape shaping us, and can we shape the threat landscape? Given the bewildering pace at which technology changes and new threats appear, how do we focus and prioritize our workload? What skills do we need?

Traditionally, information security groups in businesses and other organizations have taken a relatively narrow view of security risks, which resulted in a correspondingly narrow charter. We focused on specific types of threats, such as malware. To combat these threats, we applied technical security controls. In an attempt to protect against attacks and stop them reaching business applications and employees PCs, we fortified the network perimeter using firewalls and intrusion detection software. To prevent unauthorized entry to data centers, we installed physical access control systems. Overall, our thinking revolved around how to lock down information assets to minimize security risks, and how to reactively detect and respond to risks as they presented themselves.

Today, however, I believe that this narrow scope not only fails to reflect the full range of technology-related risk to the business; it is detrimental to the business overall. Because this limited view misses many of the risks that affect the organization, it leaves areas of risk unmitigated and therefore leaves the organization vulnerable in those areas. It also makes us vulnerable to missing the interplay between risks and controls: by implementing controls to mitigate one risk, we may actually create a different risk. And by focusing primarily on detection and response, we are not preventing harm; we are just trying to limit the damage.

As Ill explain in this book, we need to shift our primary focus to adopt a broader view of risk that reflects the pervasiveness of technology today. Organizations still need traditional security controls, but they are only part of the picture.

There are several reasons for this. All stem from the reality that technology plays an essential role in most business activities and in peoples daily lives.

Technology has become the central nervous system of a business, supporting the flow of information that drives each business process from product development to sales. In addition, as Ill discuss throughout this book, almost every company is becoming a supplier of technology in some form, as technology becomes a vital element of most products, services, and infrastructure from cars and household appliances to the power grid.

The role of technology in peoples personal lives has expanded dramatically, too, and the boundaries between business and personal use of technology are blurring. Marketers want to use social media to reach more consumers. Employees want to use their personal smartphones to access corporate e-mail.

Meanwhile, the regulatory environment is expanding rapidly, affecting the way that information systems must manage personal, financial, and other information in order to complyand introducing a whole new area of IT-related business risks.

Threats are also evolving quickly, as attackers develop more sophisticated techniques, often targeted at individuals, which can penetrate or bypass controls such as network firewalls, traditional antivirus solutions, and outdated access control mechanisms such as passwords.

In combination, these factors create a set of interdependent risks to a businesss information and technology, from its internal information systems to the products and services provided to its customers, as shown in Figure .

Figure 1-2.

Managing the interdependent set of technology-related risks

Traditional security or other control type thinkers would respond to this situation by saying no to any technology that introduces new risks. Or perhaps they would allow a new technology but try to heavily restrict it to a narrow segment of the employee population. An example of this over the past few years was the view at some companies that marketers should not engage consumers with social media on the companys web site because this meant accumulating personal information that increased the risk of noncompliance with privacy regulations. Another example was that some companies didnt allow employees to use personal devices because they were less secure than managed business PCs.