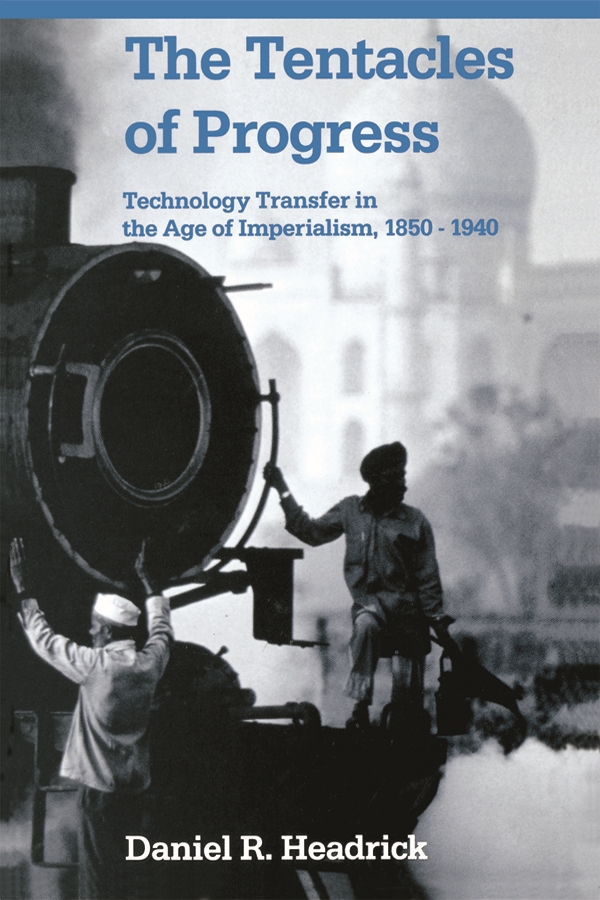

Daniel R. Headrick - The Tentacles of Progress

Here you can read online Daniel R. Headrick - The Tentacles of Progress full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: OUP Premium, genre: Business. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Tentacles of Progress

- Author:

- Publisher:OUP Premium

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Tentacles of Progress: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Tentacles of Progress" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Tentacles of Progress — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Tentacles of Progress" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Oxford University Press

Oxford New York Toronto

Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi

Petaling Jaya Singapore Hong Kong Tokyo

Nairobi Dar es Salaam Cape Town

Melbourne Auckland

and associated companies in

Beirut Berlin Ibadan Nicosia

Copyright 1988 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Headrick, Daniel R.

The tentacles of progress.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. ImperialismHistory. 2. Technology transfer

History. 3. Great BritainColoniesHistory.

4. TropicsEconomic conditions. I. Title.

JC359.H39 1988 338.926 87-5617

ISBN 0-19-505115-7

ISBN 0-19-505116-5 (pbk.)

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

Many people contributed to this book, though they may not have known it at the time. I wish to thank them all.

My thanks go first to the many archivists and librarians without whom this book would not exist, especially those at the following institutions: in Chicago, the libraries of the University of Chicago and Roosevelt University; in France, the Bibliothque Nationale, the Archives Nationales and its Section Outre-Mer, the Bibliothque dAfrique et dOutre-Mer, the Institut de Recherches Agronomiques Tropicales, and the Musum National dHistoire Naturelle; and in Britain the India Office Records and Library, the British Library, and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

I also owe a great debt to the many people who gave me their support and encouragement, and much valuable information, among them Margaret Anderson, Andr Angladette, Ralph Austen, Georges Ballard, Bertrand de Fontgalland, Alexander de Grand, Fritz Lehmann, William McCullam, William H. McNeill, Phyllis Martin, David Miller, Joel Mokyr, David Northrup, the late Derek de Solla Price, Joel Putois, Theodore W. Schultz, and Gary Wolfe.

I also wish to thank my editors at Oxford University Press, Nancy Lane, Rosalie West, and Joan Bossert.

And finally I wish to express my gratitude to the National Endowment for the Humanities, whose generous financial support gave me the time to write this book.

This book is dedicated to Cecil and the memory of Edith, and to Sol and Gertrude.

D.R.H.

Chicago

October 1986

A great hope arises every few years that the poorer countries of the world can develop their economies with the help of capital and technology from the industrial nations. Then, after awhile, despair sets in, and the fate of the less developed nations once again seems grim. Such recurring bouts of expectation and disillusionment go back well over a century. As early as 1853, at the start of a great wave of European investments in the tropics, Karl Marx predicted:

I know that the English millocracy intend to endow India with railways with the exclusive view of extracting at diminished expense the cotton and other raw materials for their manufactures. But when you have once introduced machinery into locomotion of a country, which possesses iron and coals, you are unable to withhold it from its fabrication. You cannot maintain a net of railways over immense country without introducing all those industrial processes necessary to meet the immediate and current wants of railway locomotion, and out of which there must grow the application of machinery to those branches of industry not immediately connected with railways. The railways system will therefore become, in India, truly the forerunner of modern industry. This is the more certain as the Hindus are allowed by British authorities themselves to possess particular aptitude for accommodating themselves to entirely new labour, and acquiring the requisite knowledge of machinery.

Almost a century later, in the year of Indian independence, the economic historian T. S. Ashton concluded his book The Industrial Revolution, 17601830 with the rueful remark:

There are today on the plains of India and China men and women, plague-ridden and hungry, living lives little better, to outward appearance, than those of the cattle that toil with them by day and share their places of sleep by night. Such Asiatic standards, and such unmechanized horrors, are the lot of those who increase their numbers without passing through an industrial revolution.

Despite a century of European rule, India had not become industrialized as Marx had expected, nor had any other non-Western country except Japan. Yet they were not untouched by the upheavals of that century. Theirs was no simple delay in some inevitable process of industrialization, but another, less welcome evolution: the transformation of traditional economies into modern underdeveloped ones.

The period with which this book is concernedfrom the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentiethstretches approximately between these two statements. It does not coincide with the usual periodization of history based on political and military events in Europe, which distinguishes sharply between the nineteenth century (i.e., 18151914) and the twentieth (1914 to the present). For Europe, 1914 was a significant turning point, marking the end of a century of peace and the beginning of a new Thirty Years War. For Asia and Africa, however, 1914 was the middle of the colonial era. This era was one of unprecedented change. Though there had been many empires in the past, never before had one civilization overwhelmed all the others and set them on an entirely new course.

The beginning of our era, in the mid-nineteenth century, is approximate. While the scramble for Africa has gained great notoriety, Western pressure on Africa and Asia was already apparent earlier in the century; witness the Opium War (183942), the explorations of Africa, the war of the Indian Rebellion (185758), and the openings of the Suez Canal (1869). What these events have in common is not only the fact of Western intrusion, but the technical innovations which gave Europeans the power to intrude. And at the other end of our era, it was World War II, not World War I, which set off the disintegration of the European colonial empires.

This era, the new imperialism, coincides with the creation of modern underdeveloped economies in Asia and Africa. While these two processes have often been linked, their relationship remains unclear. A consideration of the technologies involved can shed some light on this question.

The history of technology once consisted only of nuts-and-bolts stories of great inventors and famous engineers. Today, technologies are no longer viewed as externalities that arise fortuitously from the minds of geniuses, but as an intrinsic part of the culture and economy of every society. And the task of the social historian of technology is to study the economic and cultural context in which innovations arise and, in turn, their impact upon the societies in which they appear.

Within this contextual tradition, our approach is to reverse the question. Not only does every technology exist in a social context, all events and all social situations occur in a technological context. Given an event or situation, we may ask, What is that technological context, and what part do technological changes play in it? This approach is familiar to those who study the Great Discoveries, the Industrial Revolution, and the winning of the American West. It needs to be applied to the study of the European empires as well.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Tentacles of Progress»

Look at similar books to The Tentacles of Progress. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Tentacles of Progress and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.