Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the work of Ms Deborah Debono at the Centre for Clinical Governance Research, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, University of New South Wales who unstintingly gave her time and expertise in coordinating the efforts of the editors and authors, and ensuring the copy and proofs were of high quality. Ms Margaret Jackson proof-read the entire manuscript and we record our appreciation to her, too.

Also by Jeffrey Braithwaite

EVIDENCE BASED MANAGEMENT IN HEALTH CARE: the role of decision-support systems (with Boldy, D. and Forbes, I.W.)

WORKPLACE INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS IN THE AUSTRALIAN HOSPITAL SECTOR

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE CHANGING FACE OF HEALTH SERVICES MANAGEMENT IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC RIM (with Forbes, I.W.)

Also by Paula Hyde

ORGANIZING AND REORGANIZING: Power and change in health care organizations (with McKee, L. and Ferlie, E.)

Also by Catherine Pope

SYNTHESIZING QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE HEALTH EVIDENCE: a guide to methods (with Mays, N and Popay, J.)

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH IN HEALTH CARE (3rd Edition) (with Mays, N.)

Box

1

Converging and Diverging Concepts in Culture and Climate Research: Cultate or Climure?

Jeffrey Braithwaite, David Greenfield and Mary T. Westbrook

Introduction

Are culture and climate different aspects of organizations, or are they the same general construct? In one sense, there is an easy way to cut through the tangled thicket of this question. It depends on the definitions used to explain the concepts, and the perspectives taken in characterizing them. In this paper, we briefly trace the roots of the terms culture and climate, and discuss their manifestations and conceptualizations in contemporary theory and research. Although it is clear that much depends on how culture and climate are defined, we emphasize the commonalities and explore the links between them. We introduce some evidence drawn from an Australian study of 22 randomly sampled, stratified health care organizations. This was part of a large-scale national research project into health sector organizational behaviour. The findings provide a gateway into understanding contrasting and converging views of culture and climate, particularly in terms of statistical relationships between the two concepts. The implications of this for research, practice, and teaching are discussed.

The roots of culture and climate

Historically, culture and climate are sometimes seen as distinct organizational variables; sometimes, as arising from differing academic traditions; and sometimes, as rival theoretical concepts. Alternatively, they have been viewed as two sides of the same coin, reflecting similar manifestations of the way things are done around here representing the shared perceptions, values and meaning-making that people employ to co-construct their organizational worlds. No one, so far as we are aware, has conjoined the concepts by advancing a hybrid term such as cultate or climure.

Conceptually, although it is not as easy as it might seem to cleave the two constructs, climate emerged from an early concern for the measurement of individual attitudes, and has often been of interest to industrial or social psychologists. One question testing climate researchers historically was the relationship between data on individual attitudes obtained via questionnaire surveys and aggregations of these data. Climate has since expanded to be viewed by many as a systems-wide, organizational-environmental construct, metaphorically akin to the weather.

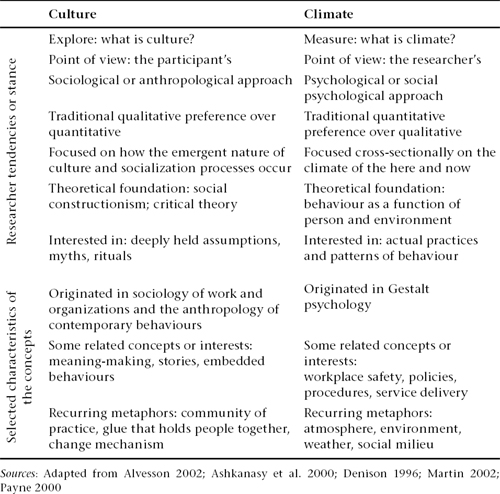

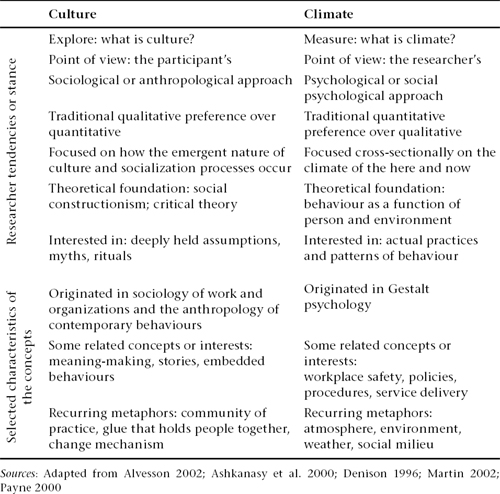

More often than not, culture is also conceived broadly, not so much as an organizational variable but as a way of understanding or expressing organizational life holistically, that is, the sum total of enacted behaviours, meanings and attitudes. A problem challenging culture researchers is the way in which many cultures manifest; is it feasible to see one meta-organizational culture, multiple sub-cultures, or many micro-cultures? Culture has traditionally been the domain of anthropologists, sociologists, or sociologically oriented scholars of organizational behaviour. Although it is not as clear-cut as the table suggests, and without claiming to be exhaustive, we can synthesize what scholars have said by looking at contrasting and converging views of culture and climate ().

Having presented the divisions this way, it should be stressed that many scholars have concluded that whatever distinctions there once were between the two concepts, these are now muddied and they essentially examine similar organizational features. Both attempt to describe organizational members experiences with, and construction of, their workplace landscapes. Perhaps those investigating climate focus more on psychometrics, and cultural investigators ethnographically explore the world of peoples lived experiences, but for many commentators it is difficult to distinguish between culture and climate, and some leading thinkers, including those in the Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate (Ashkanasy et al., 2000) have shown how hard it is to maintain these differences.

Manifestations and conceptualizations of culture and climate in contemporary theory and research

Theoretical models culture

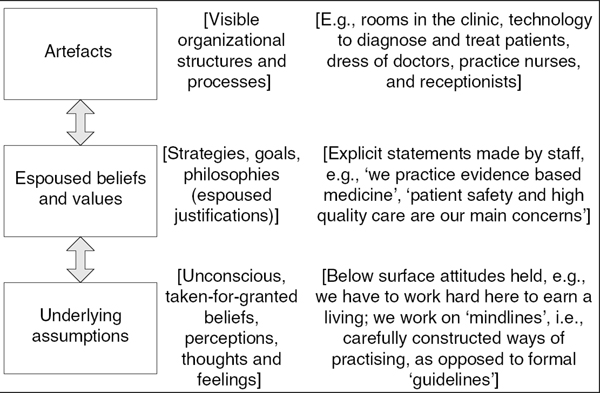

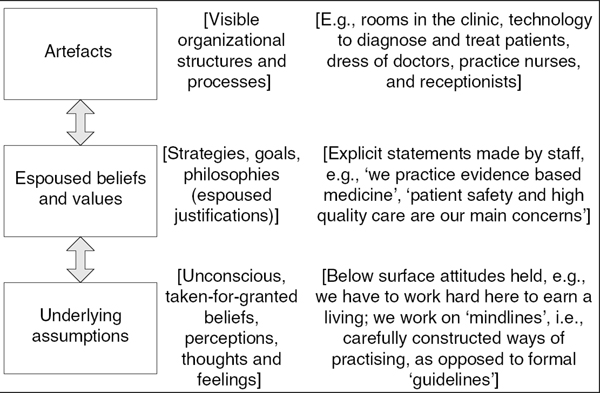

We can consider culture and climate further by examining models which, according to the predilections of the writers, have been used to capture the main explanatory variables. A tripartite model has been advocated by Schein (2004), who suggests that there are levels of visibility to which observers of a culture can attend. shows the Schein model with examples from a hypothesized general practice.

Table 1.1 Contrasting and converging views of organizational culture and climate

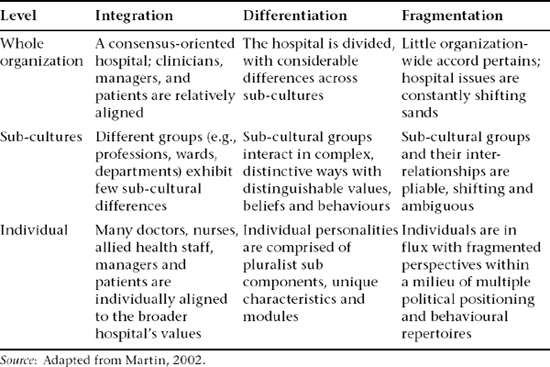

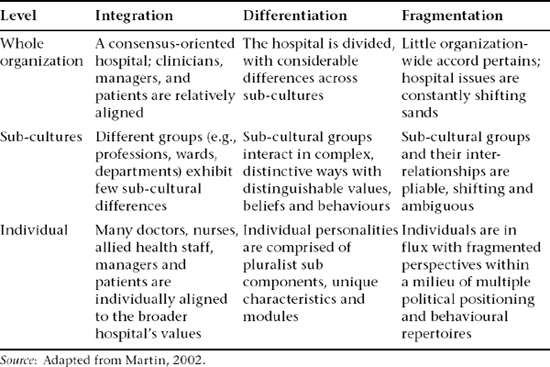

Martin (2002) sees culture differently, construing it as an expression of a wide range of complex variables. She presents three conceptual perspectives. The integrationist perspective attends to the consistencies and agreements that manifest. The differentiationist perspective looks at inconsistencies that emerge, for example in terms of subcultures. The fragmentationist perspective sees culture as ambiguous and transitory. One seductive way to understand this model is by mapping the three perspectives to an organizations levels. At the level of the whole organization, cultural features which are shared, or often promoted normatively by the occupants of the executive suite, are organizational-wide and reinforced by corporate policies and imposed or articulated values. At the meso, or intermediate organizational level, differences in terms of gender, profession, between departments or across various groups, teams and networks , adapted from Martin, shows how the perspectives map to three levels of analysis, in this case of a hypothetical teaching hospital.

Figure 1.1 Scheins levels of culture with examples drawn from a general practice

Source: Adapted from . Levels of Culture in Schein, Edgar H., Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2004:26 (Reprinted by permission of the publisher John Wiley & Sons Inc.).

Table 1.2 Martins three cultural perspectives applied to a teaching hospital