The 80/20 Principle

The 80/20 PrincipleThe 80/20 principle states that there is an inbuilt imbalance between inputs and results in any system. Typically, the majority of the inputs have little impact on the results while a minority have a major impact. In other words, the bulk of the results are actually derived from only a small proportion of the inputs.

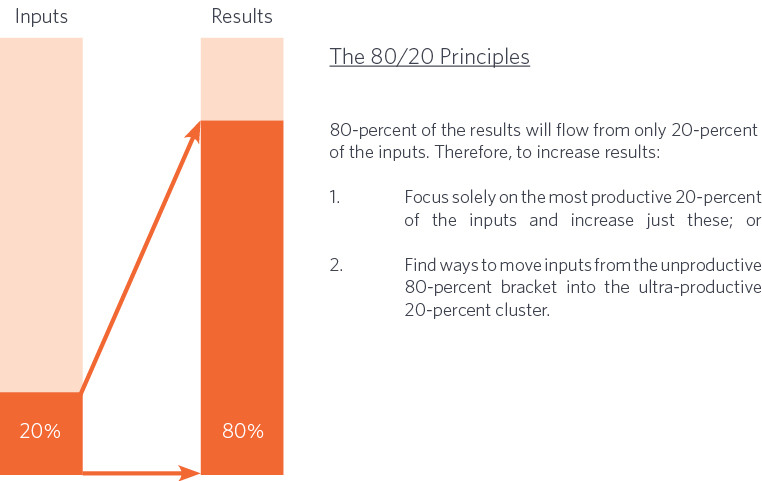

A mathematical benchmark which consistently shows up is that 80-percent of results directly flow from just 20-percent of the efforts. Therefore, the key to being more productive is to:

- Determine which 20-percent of the total effort is most productive, and to focus on increasing those inputs in order to achieve even greater results.

- Find ways to make the 80-percent that is currently unproductive become more productive.

The basic underlying premise of the 80/20 principle was first identified by an Italian economist, Vilfredo Pareto, in 1897. Pareto was studying patterns of wealth and income in 19th century England, and he noticed that there was a consistent mathematical relationship in evidence. Specifically, Pareto noticed 20-percent of the population had accumulated 80-percent of the wealth, and that the same relationship was repeated consistently in numerous other areas. (The 80/20 principle is sometimes referred to as the Pareto Principle in his honor.)

The 80/20 principle was publicized by George K. Zipf, a Harvard professor and by Joseph M. Juran, the prime mover behind Japans quality revolution which started around 1950. The 80/20 principle has also attracted a number of titles, including the rule of the vital few, the principle of least effort and the principle of mathematical imbalance.

The concept that greater results can flow from some inputs more than others is both counter-intuitive and counter-democratic. Nevertheless, it can provide valuable insights into improving a persons personal productivity by identifying which areas should be emphasized in order to maximize results. On a corporate level, the 80/20 principle can successfully identify which resources are most productive, and which can be eliminated with minimal effect on overall results.

Some examples of the 80/20 principle include:

- 80-percent of the worlds energy is consumed by 15-percent of the population.

- 80-percent of the worlds wealth is possessed by 25-percent of the worlds population.

- In health care, 20-percent of the population will require 80-percent of the total medical expenditure.

- For most non-fiction books, 80-percent of the new ideas are contained in 20-percent of the text.

- 20-percent of the new movies released each year generate 80-percent of the industrys total box office revenues.

- 20-percent of the companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange generate 80-percent of the growth (or decline) in overall market value each year.

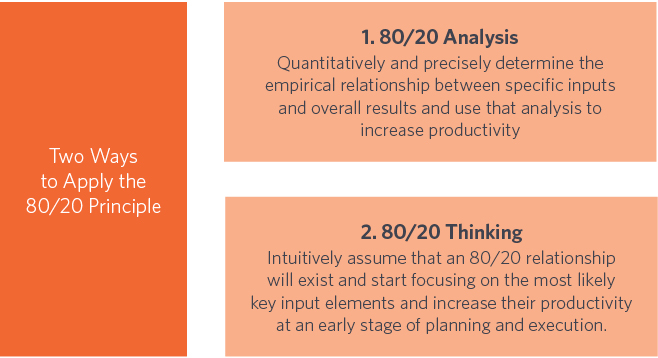

There are two ways to apply the 80/20 principle:

- 80/20 Analysis

This is the traditional approach to the 80/20 concept. It requires that the possible existence of an 80/20 style relationship be assumed, and data be quantitatively gathered to determine what the exact imbalance is. (It may be shown to be 75/25 rather than 80/20, and so on).

Under this approach, resources can then be focused on the key smaller proportion of the inputs to maximize results. Alternatively, as already mentioned, attention can be turned to increasing results from the under performing major proportion of inputs.

- 80/20 Thinking

An alternative approach suggests that rather than wait for a precise 80/20 pattern to become measurable, why not approach each situation as if an 80/20 relationship will later become apparent, and look for the key 20-percent input to focus on while ignoring the majority of factors which will later be seen to be of only marginal value.

80/20 Thinking proposes taking a proactive approach - try and identify which small number of inputs will exert disproportionately greater influence on the results through some creative thinking. It necessarily involves making some preliminary attempts that may later prove to be incorrect.

The long-term advantages of both 80/20 Analysis and 80/20 Thinking are:

- Exceptional productivity will be focused on rather than trying to raise the average results of all inputs.

- An intuitive approach to look below the details of everyday life to patterns of productivity underneath the surface can be encouraged and enhanced.

- Productive short-cuts will be sought rather than doing things the long way.

- In your personal life, you can simplify matters, accomplish more and work less by focusing on the achievement of a limited number of highly valuable personal goals rather than a large number of marginal goals.

- A company can determine which 80-percent of work can be outsourced cost effectively while resources are more intensely focused on key productive activities.

- An inclination to focus on excellence in a few key factors will be encouraged instead of trying to achieve average results in a broader number of factors.

The reasonable man adapts himself to the world. The unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.

--George Bernard Shaw

God plays dice with the universe. But theyre loaded dice. And the main objective is to find out by what rules they were loaded and how we can use them for our own ends.

--Joseph Ford

Business Applications of the 80/20 Principle

The top ten business applications of the 80/20 principle are:

- Strategy

- Quality

- Cost reduction and service improvement

- Marketing

- Selling

- Information technology

- Decision making and analysis

- Inventory management

- Project management

- Negotiation

1. Strategy

Most companies generate 80-percent of overall profits from 20-percent of activities and 20-percent of total revenues. Usually, the hard part lies in working out which 20-percent is the most productive.

To take advantage of this, break down your company operations:

- By product or product group

- By customer or customer group

- By any other split which is directly relevant to your operations

- By competitive segment

Of the four options, breaking operations down by competitive segment is usually most valuable. A competitive segment is a part of your operations where either you face a different competitor or differing competitive dynamics are in use. For each competitive segment in which you compete:

- Analyze your competitor - where are they strongest, and where do you secure sales away from them?

- Evaluate whether or not the segment is an attractive market to be in.

- Consider how your company is positioned in the sector, and where the greatest potential profits will be generated.

Most companies fail to actively analyze and plan on the basis of specific competitive segments. This, however, fails to take advantage of the key benefits of studying competitive segments:

- To identify which few activities carried out by your entire company generate the bulk of your profits.

The 80/20 Principle

The 80/20 Principle

Business Applications of the 80/20 Principle

Business Applications of the 80/20 Principle