First published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc,

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright 2014 text by Chris and Helen Pellant Copyright 2014 photographs by Chris and Helen Pellant

The right of Chris and Helen Pellant to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN (print) 978-1-47290-993-0

ISBN (epub) 978-1-47291-122-3

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Publisher: Nigel Redman

Project editor: Alice Ward

Design: Susan McIntyre

Printed in China by C&C Offset Printing Co Ltd.

This book is produced using paper that is made from wood grown in managed sustainable forests. It is natural, renewable and recyclable. The logging and manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulation of the country of origin.

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here .

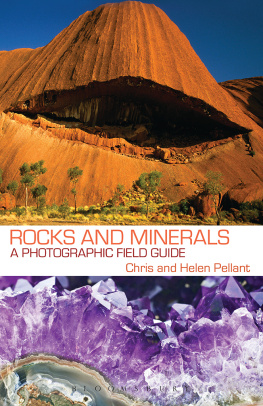

front cover: Part of Uluru (Auscape/UIG Gettyimages), Amethyst (Shutterstock)

back cover: Gypsum, Fluorite and Pyrite, Agate, Larvikite (Chris and Helen Pellant), Sandstone formation (Shutterstock)

CONTENTS

A hot spring at Rotorua, North Island, New Zealand, deposits minerals around its opening.

Citrine, an orange-brown variety of quartz, showing hexagonal pyramidal shapes and vitreous lustre. Specimen from Brazil.

Weathered pinnacles of basalt at The Storr, Skye, Scotland.

INTRODUCTION

Rocks and minerals are the basis for the structure of the Earths crust. Minerals are composed of atoms of single elements or a number of different elements. They can have perfect crystalline form and amazingly rich colours; some are prized as gemstones; many are the source of economically useful metals and other raw materials. New minerals are still being discovered, especially in industrial slag and even on shipwrecks. Rocks are made of minerals. Many, especially crystalline igneous rocks and marble, are frequently used decoratively, and certain rocks such as limestone, coal and ironstone have great economic uses. However, the Earth has been scarred by the extraction and use of these raw materials; watercourses and soils have been polluted and the atmosphere changed.

Our own interest in rocks and minerals began many years ago and is related to our delight in, and study of, the natural world. Minerals have always held a fascination and our collection has grown over the years. Many of the illustrations in the book are of our own specimens.

Making a collection of rock and mineral specimens may require fieldwork. Good locations can be researched using local geology field guides, geological maps and the internet. It is essential to obtain permission to gain access to private land and always to take great care when near cliffs or quarry faces. When breaking rocks, a geological hammer should always be used and eye protection worn. Specimens should be carefully cleaned and curated, with a card label giving location, date and other details. Fine or rare specimens can be bought from dealers.

This book is designed to help the reader identify and understand some of the more common rocks and minerals. The introductory sections outline basic formation and methods of classification and identification; the main sections, with illustrations, outline each of the rocks and minerals. The items selected and illustrated are those which may be found or obtained with relative ease.

Zigzag folding of alternating sandstone and shale at Millook Haven, Cornwall, England.

Granite exposure, Guernsey, Channel Islands, showing characteristic jointed structure emphasised by weathering.

ROCKS

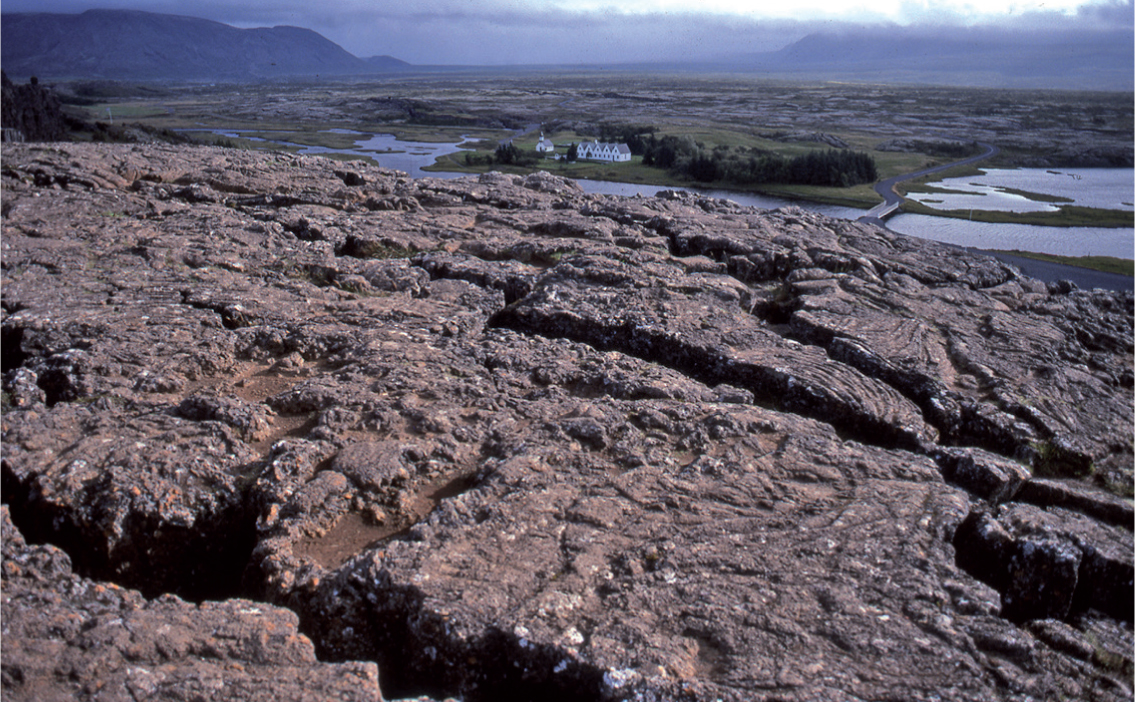

Rocks are the basic materials of which our planet and many others in the solar system are composed. They are aggregates of minerals, commonly a few, sometimes only one or two. Dark crystalline basalt and loose sand both fit this definition. The characteristic features of any rock, and hence the means by which it can be identified and named, are a direct result of how it formed. Rocks are thus divided into three broad groups, the igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks. Igneous rocks result from the cooling and consolidation of magma or lava; metamorphic rocks are those which have been changed from their original state by heat and/or pressure; sedimentary rocks are usually deposited in strata (layers) and may result from the weathering and erosion of pre-existing rocks.

Rocks form in a cycle. The first to develop, the primary rocks, are the igneous rocks. Magma (molten rock underground) and lava (molten rock on the surface) come from some depth in the crust or upper mantle of the Earth. Once magma or lava has cooled, and igneous rocks have formed, weathering and erosion can break them down into their constituent minerals, some of which may be further altered. The feldspar in granite, for example, can be converted into clay by weathering processes. The grains resulting from weathering and erosion can be transported by running water, ice or wind and deposited as sediments in the sea, a lake or elsewhere on the land surface. In time these become sedimentary, secondary, rocks. Through depth of burial and the movement of the Earths crust resulting from plate tectonic events, rocks are changed by heat and pressure to become metamorphic rocks. These in turn, if they are buried deep enough, may melt and create new magma to start the cycle again.

We are reliant on rocks, and the minerals they contain, for much of what we need. They provide our raw materials, from metals to fuel and chemicals, and our land is fertilised for crop production with chemicals derived from rocks. However, the Earths crust has been unsustainably plundered and the rock cycle is being changed as the climate is altered by excessive use of fossil fuels.

IGNEOUS ROCKS