Other Books by William Safire

LANGUAGE

On Language

In Love with Norma Loquendi

Quoth the Maven

Coming to Terms

Fumblerules

Language Maven Strikes Again

You Could Look It Up

Take My Word for It

I Stand Corrected

Whats the Good Word?

Watching My Language

Spread the Word

Let a Simile Be Your Umbrella

No Uncertain Terms

The Right Word in the Right Place at the Right Time

Safires New Political Dictionary

POLITICS

The First Dissident

Safires Washington

Before the Fall

Plunging into Politics

The Relations Explosion

FICTION

Full Disclosure

Sleeper Spy

Freedom

Scandalmonger

ANTHOLOGIES

Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History

ANTHOLOGIES

(with Leonard Safir)

Good Advice

Good Advice on Writing

Leadership

Words of Wisdom

Copyright 1990 by The Cobbett Corporation

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 2005

Previously published as Fumblerules

Book design by Margaret M. Wagner

Production manager: Amanda Morrison

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

ISBN 978-0-393-32723-6

ISBN 978-0-393-35136-1 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

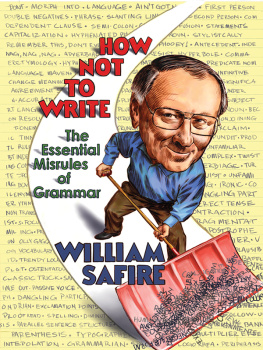

How

Not

to

Write

W hat kind of word is intro for the beginning of a book laying down rules of grammar and usage? Its a clipped word, slang, a breezy informality entirely inappropriate to the job at hand.

Intro , lets face it, is a mistake in this highly literate context. Introduction with its Latin meaning of to lead withinwould be not only correct, but also more apt, considering the double meaning of lead . Better still would be prolegomenon , pronounced pro-le-GOM-en-on, which smacks of pedantry but would at least stop readers who automatically skip introductions.

But the sassy intro at the head of this non-sassy preface illustrates the essence of a fumblerule: a mistake that calls attention to the rule. The message: See how wrong this looks? Do as I say, not as I do.

We smile at the fumblerules mistake and tell ourselves were pretty smart not to do that dumb thing. With that boost to our grammatical self-esteem, we are prepared to swallow a little pedagogy. Not that any of us need it; were all native speakers and dont need grammarians to tell us how to use our own language; still, were made ready, by this device, to buy a bit of explanation.

Schoolteachers have been compiling lists of fumblerules for generations, posting them on bulletin boards and mailing them around. I ran a New York Times Magazine column listing some a few years ago and received scores more in the mail. Culled, winnowed, beefed up and edited, here are the best: a ferocious farrago of instructive error, each with an accompanying explanation, designed to straighten you out without weighing you down.

The most graphic fumblerule of all can be found tacked on office and school walls throughout the English-speaking world: Plan Ahead, it says, with the last letters squeezed together, and the final d almost crowded off the page. Thats the idea behind How Not to Write . Now lets apply it to the way we write and speak.

W hat happens when you use a word that is not a verb, or write a phrase that does not contain a verb, as if it were a complete sentence? You see lying dangerously on the page a shard of prose called a sentence fragment .

Fragmentation occurs when an end mark of punctuation (period, question mark, exclamation point) follows an incomplete sentence.

As grammarians say, if you aint got a verb, you aint got a sentence. (Permissive grammarians.) To be a sentence, a run of words must be a complete thought, with a subject and a predicatein other words, it must be about something or somebody taking action or being something.

Take the parenthetical words two sentences back, Permissive grammarians; the phrase should not be followed by a period because the thought is not complete. If I wanted to add an afterthought, I should have written, (Permissive grammarians say that, to show their familiarity with dialect.) The verb say makes it a sentence.

Not all sentence fragments are to be avoided. Why not? Because of their rhetorical effect. (The last two non-sentences are fragments that make my point. Is this a good pedagogical technique? Not always.)

A one-word sentence is possible only if the word is a verb in the imperative mood, with the subject clearly implied. Consider the Army sergeant who wishes to convey this message: Because of the screaming sound you all hear of an incoming smart bomb, it behooves us all to evacuate this area. Instead, he will holler: Run! Although military purists will argue that he should shout Cover!, his grammar is correct.

Enough of this page. (Fragment.) Turn! (Complete sentence.)

A run-on, as every banker knows, is any incorrect joining of sentences.

One wrong method is fusion, the simple jamming together of two complete, stand-alone thoughts, as in our fumblerule. William Faulkner and James Joyce did that a lot and got away with it you are not them I am not them either.

A trickier wrong method is the comma splice, which joins two separate sentences with a comma that is just not up to the job. Dont do that, try something else. (Aha! That was a comma splice; see how awkwardly it slaps together the two thoughts?)

Here are three right ways to connect sentences:

1. Separate the main clauses with a semicolon, a form of punctuation that makes a full stop but continues to dribble. Note the artistic, stylish double sentence in the above paragraph, after the Aha!the use of the semicolon avoids the choppiness of two short sentences, but seems to bring the second thought closer to the first, as if the two ideas were inseparable. (Never use a dash when a semicolon is called for, as I just did after the second Aha!)

2. Use a conjunction, or as Kissingerians used to say, employ linkage. And, or and but coordinate separate thoughts evenhandedly, while as, because, if, when, though gently subordinate the clause that follows.

3. I lied; there are only two ways to connect sentences, and I used them both in this sentence.

Happily, a third choice is available to you: Do not connect two independent thoughts at all. Nowhere is it written that sentences require more than one complete thought.

Instead of linking, decouple. Use a period. Be choppy. Sometimes thats a strong way to write. Just dont do it too often or for too long. It makes the reader think you think hes a dope.

Next page