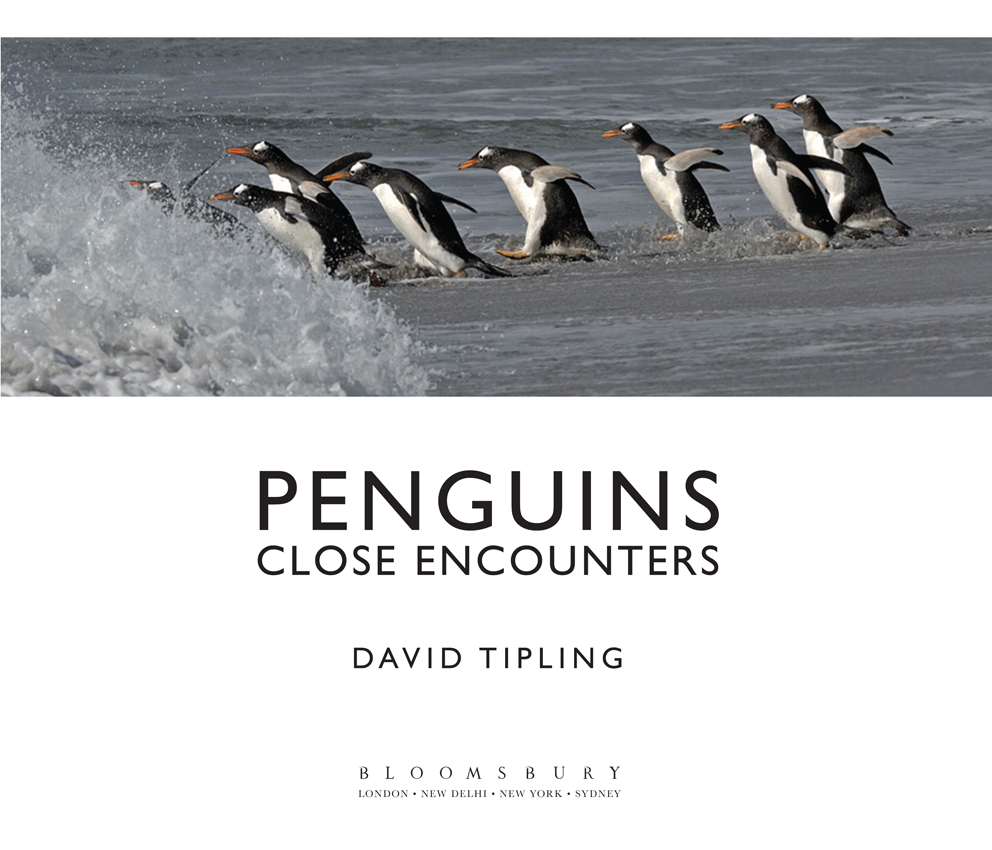

First published in 2013 by New Holland Publishers

This edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright 2013 in text: David Tipling

Copyright 2013 in photographs: David Tipling (and other photographers as credited below)

The right of David Tipling to be identified as the author and photographer of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Publisher: Nigel Redman

Designer: Lorena Susak

ISBN 978-1-4729-1082-0

This book is produced using paper that is made from wood grown in managed sustainable forests. It is natural, renewable and recyclable. The logging and manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulation of the country of origin.

All images by David Tipling except the following: Nigel McCall (page 153), Pete Morris (

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here.

Contents

Introduction

Never have I felt so alive in spirit or so vulnerable to death as the day I photographed Emperor Penguins during an Antarctic storm. It was 11 November 1998 and I had spent 10 days camping on the sea ice in the Weddell Sea, not far from the very spot where Lord Shackleton had abandoned his ship the Endurance in 1915. A storm had swept across from the west and, with icy winds in excess of 80kph (50mph), it had blown up into a raging white out. The sea ice groaned and, more worryingly still, it was beginning to crack. A few hours earlier I had sat in my tent clinging to the roof while it lurched violently in the strong gusts. Yet, as conditions improved a little, I made it back to the Emperor Penguin colony in which I had immersed myself for days. I had photographed the life of a bird that is, for me at least, the ultimate. No other warm-blooded animal on Earth endures such intense cold or has such an extraordinary breeding strategy.

In that vile hurricane I stood very close to the Emperors at least 200 chicks huddled together in a crche surrounded by their braying parents. I worked quickly to create more images, but somehow photography seemed secondary in this incredible moment. Somewhere out there was the rest of the expedition team with whom Id travelled to this remarkable place, but they were all invisible to me in the endless blast of snow. I was alone with these birds, and it felt special, as if I were living another life, cut off from the world I had left far behind. Even as I stood there amid all that snow and surrounded by all these sheltering birds, I realized that I was witness to a spectacle and party to a moment coming but once or twice in any lifetime.

It was also hard to believe that just ten days before this wonderful intimacy with the Emperors among such savage beauty, I had had my first ever sighting of a penguin. In truth it could not have been a more different experience, nor a more remote kind of encounter. It came from the seat of the aircraft in which we flew to the Emperor colony. At 3,700m (12,000ft) elevation, a group of what may have been Chinstrap or Adlie Penguins looked like mere atoms of darkness scattered across a vast iceberg afloat in the Southern Ocean. I was peering out of the cockpit window and below me a land of incredible beauty was slowly unfolding. We were on a six-hour flight from Punta Arenas in Chile to Patriot Hills, a summer camp at the base of the Ellsworth Mountains situated at 80S and just 966km (600 miles) from the South Pole. From here I would be flying another 1,100km (700 miles) to the Dawson-Lambton Glacier.

Our wheeled Hercules touched down on the blue ice runway at Patriot Hills and was described by our pilot as real seat-of-the-pants flying. If Im honest, by the time we came to a halt I was in need of a change of underwear! The aircraft slewed and snaked across the ice. Then as I walked down the ramp of the Hercules the cold was brutal. For the next three weeks I was going to be camping on that ice. I remember thinking at the time: itll be like living in a chest freezer. When I washed my hair in a bowl of steaming water it froze immediately afterwards into hard icy spikes. When katabatic winds roared down at us from the South Pole bringing hurricane-force gales, any flesh exposed even for a few seconds would be frostbitten.

Patriot Hills was home as the storms swept across us, but when a break in the weather came a few days later we set off finally for the Dawson-Lambton Glacier. As we flew over the frozen Weddell Sea, the view below was exhilarating. Massive tabular icebergs sat within a white plane of pack ice and towered over row upon row of enormous deep-blue pressure ridges, whose crystalline edges sparkled in the brilliant sunlight. Yet the strongest memories from that day in early November 1998 are of my first real penguin encounter.

We had landed on the sea ice and set up camp and had then walked in the early hours of the morning around 1.5km (1 mile) along the edge of a towering ice-cliff to an Emperor Penguin colony. An extract from my diary recounts the experience:

Still out of sight but just a few steps away the sounds of adults trumpeting and chicks peeping quickened our stride. Then ahead of us were thousands of Emperors clustered together in seven sub-colonies within an amphitheatre of sculpted ice, the low light washing a warm glow over the birds. I soon got to work making many pictures. By 8am I felt exhausted and retired to camp for bread and fried eggs. I slept until 4pm and after a quick snack went back to the penguins, where after a short search I found a tiny chick being brooded on its parents feet. I sat for many hours in this corner of the colony, often adults and chicks approached touching my boots with their beaks.

That first encounter with penguins had me hooked. Since then I have peered into sea caves at fluffy Little Penguin chicks in New Zealand, strolled with Gentoo Penguins along the sandy beaches in the Falklands and stood and marvelled at King Penguin colonies that stretch for as far as the eye can see.

I realize that I am not alone in having such deep feelings for these birds. My passion is shared by people all over the world. Testament to this is the huge success of films like March of the Penguins (2005) and Happy Feet (2006). The first of these is the second highest grossing documentary at the box office. It was created at the Emperor Penguin colony at Dumont dUr ville, in the Antarctic region known as Adlie Land, and follows the birds complete breeding cycle. The anthropomorphic qualities of this remarkable species, with its waddling upright gait and arm-like flippers, easily translated into a human story about love, family values and survival.

Next page