About the Author

Award-winning author Opal Dunn has many years of experience in teaching children aged up to 8 years, and has trained teachers all over the world. She has also authored picture books for nursery and young primary children, organised Bunko (mini-libraries) for bilingual and plurilingual children, and has written information books and articles for parents.

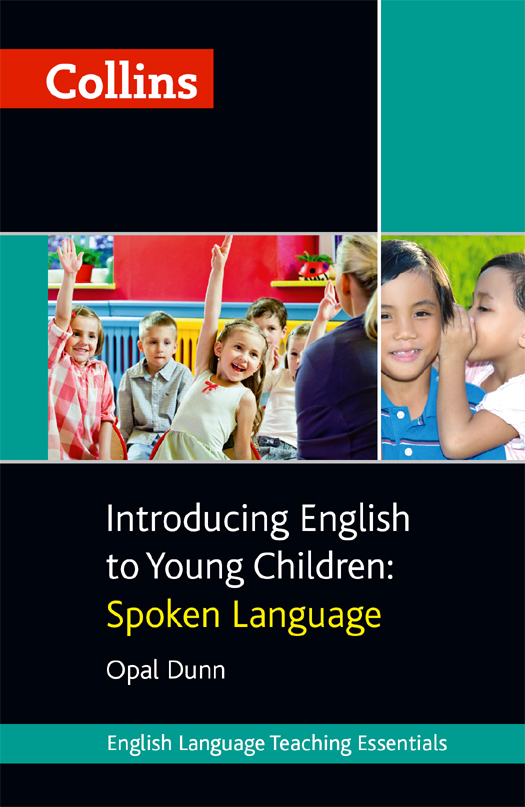

About this book

Together with its sequel, Introducing English to Young Children Reading and Writing, this book is an overview of what I have observed and experienced during many years of teaching, training teachers, organising bunko (mini-home-libraries) and helping parents of young children. My experience has been in the Far East, Europe, North Africa, South America and also England, where many young children are coming to school with no English. Every English learning situation is different; every child, and his or her home situation, is unique. What I have written aims to help teachers and carers understand better how each childs holistic development is embedded in and entwined with learning language.

Introducing English cannot be thought of only in terms of linguistic attainments. Educationalists including Froebel, ) and Whitehead, explain that children acquire and find out about language through doing, experimenting and imitating. Children are born natural language acquirers and users; most can acquire English if supportive adults provide them with sufficient language-based doing activities activities that are right for their developmental level and in which they feel confident to use their personal language-learning strategies. For very young and young children, English is another way of talking about and communicating their needs and interests to sympathetic listeners. It is important for young learners that English should be like learning to talk with their mother a living and useful skill rather than being an abstract, taught subject.

More than half the worlds young children speak two or more languages outside school and many millions are now learning English in schools. Some teachers tend to underestimate very young and young childrens innate drive and potential to pick up English as another language. Each child is an individual and in order for children to acquire English in school situations and make and enjoy the progress of which they appear capable, adults have to tune into their thinking, language, expectations and society, seeing things through their eyes.

Learning English should be a fun experience for everyone; the child, the teacher and the family all need to feel good about it if the child is to develop the positive lifelong attitudes that are known to be formed before the age of 8 or 9 years. Since many school activities include culture, young children naturally pick up the English language together with the accompanying culture that the adult mediates. The teacher is probably the young childs most important window on the English speaking wider-world a big responsibility.

These two books are written for teachers and carers working with children of preschool age to 8 years. Oral English needs to be well developed before young beginners are taught to read and write English. Introducing English to Young Children: Spoken English discusses holistic development and oral acquisition suggesting useful oral activities, mini-projects, picture books and games. Introducing English to Young Children: Reading and Writing introduces reading, handwriting and creative writing skills with suggestions for linked meaningful activities, and more advanced verbal play, games, picture books and projects.

An earlier version of this book was awarded the English Speaking Union Duke of Edinburgh award in 1985 as part of the English Language Teaching Series published by Macmillian Publishers Ltd.

The child is truly a miraculous being, and this should be felt by the educator.

( 1967)

Terminology used in this book

EFL English as a foreign language

ESL English as a second language (United States)

L1/HL first or home language (sometimes called mother tongue MT)

SL school language (which may be different from L1)

bilingual two languages in the home

plurilingual three or more languages in the home

L2 where English is the second new language

L3 where English is the third new language

L4 where English is the fourth new language

VYL very young learner (nursery school age)

YL young learn er (primary school age up to 8 or 9 years)

List of figures

We become interested in what we are good at, to quote Bruner ( 1978). This simple truth about attitudes also applies to learning English. How often adults say, I like English. I was good at it, or conversely when excusing their poor English add, I was never any good at it at school.

At no other time in life does the human being display such enthusiasm for learning, for living, for finding out ( 1979). Very young and young children normally have an inner drive to learn. They are natural language acquirers; they are self-motivated to pick up language without conscious learning, unlike many adolescents and adults. They have their own language learning skills and strategies, which develop as their brain develops and they grow physically (their skull making an effective sound box and their vocal chords and mouth forming the shapes necessary to make sounds). In the womb they hear and are listening to voices. From their first cries, children respond to their mothers soothing words in what is to become their mother tongue.

Young children seem to be tuned in to listen to language, absorb it and then use it through social interaction with supportive others to find out about the world. Their energy to ask, enquire and make sense of their world is remarkable. Parents often feel exhausted by their childs continual drive to find out: Why? Whats this? What for? How?

Learning is both social and conceptual for a young child. In making sense of every new experience, young children have to make sense of what the other person is saying and doing, confirming the known, whilst stretching and adjusting their own internal categories and theories to take in the new. They become skilled in understanding other peoples language and abstracting meaning from it. Young children are quick to decode facial language and can rapidly sense when an adult is not pleased with them.

Language and learning are social and interdependent. Thinking cannot take place without language. (1978) explained that Language is the tool of thought. External speech is the process of turning thoughts into words.

We know from observing very young children that even very little language enables participation in a social world and the sharing of meaning: Gone. Stopit. Myturn. Through natural, tuned-in supportive dialogue with an adult or more skilled older person, grammar and vocabulary is absorbed and conceptual progress may take place without any planned instruction or conscious teaching by the older person.