Contents

Guide

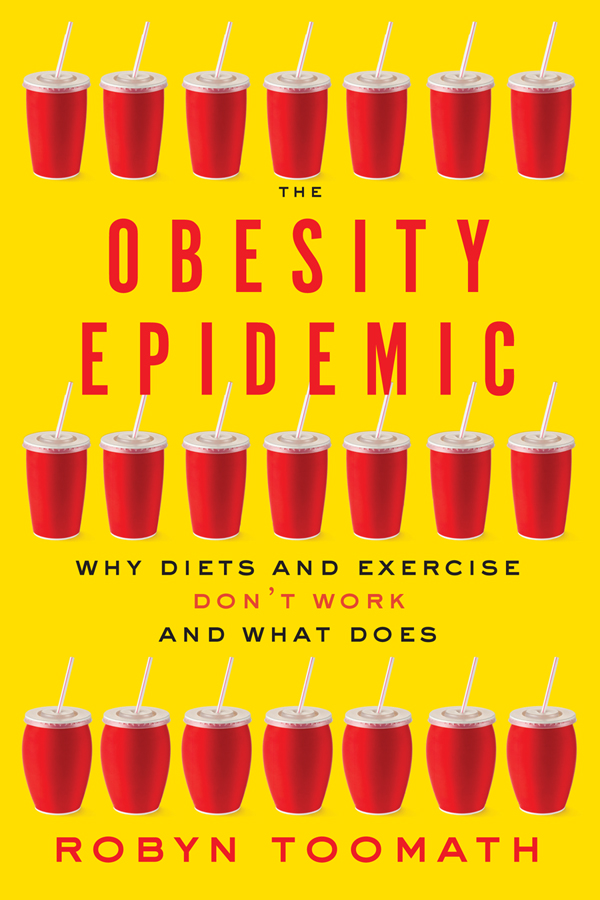

ROBYN TOOMATH works as a physician at Auckland City Hospital in New Zealand, where she is the clinical director of General Medicine. Early in her career as an endocrinologist she observed that her type 2 diabetes patients were both getting younger and increasing rapidly in numbers. Realizing that rising obesity was to blame, in 2001 she co-founded the advocacy group FOE (Fight the Obesity Epidemic) to raise awareness of this issue. As spokesperson for the organization Toomath has been constant in her call for a governmental response and public health measures to improve the obesogenic environment. She believes that making weight an issue of personal responsibility is not only ineffective but harmful to overweight individuals and has allowed industry to get off the hook. The Obesity Epidemic is the culmination of her work in this area, an effort to describe the real drivers of obesity in an in-depth and nuanced way. Toomath has also been the president of the New Zealand Society for the Study of Diabetes. She lives on Waiheke Island with her hens, Chrissie and Maisie.

The Obesity Epidemic

Why Diets and Exercise

Dont Workand What Does

Robyn Toomath

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS | BALTIMORE

2016, 2017 Robyn Toomath

All rights reserved. Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

First published in 2016 by Auckland University Press as Fat Science: Why Diets and Exercise Dont Workand What Does

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016949856

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 13: 978-1-4214-2249-7

ISBN 10: 1-4214-2249-2

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410 -- 6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

To Robin White

Contents

Do some diets work better than others? How many people who start on diets stick with them? If you lose weight, does it stay off? If not, why not?

Is exercising a good way to lose weight? How much of what sort do we have to do? Why dont more of us do more of it?

How good are diet pills? Or is surgery the answer?

Are my genes making me fat? Can we change our inheritance?

Obesity has taken off over the last 30 years. Is it the fault of television? Space food? More cars? Women working? Living in the city?

For several decades subsidies were introduced to increase food production, then to stop farmers from going broke. What do we do with the excess food? We eat it.

Arent the food industry good guys reallyjust trying to make a buck like everybody else? And now they want to help with obesity efforts too. Can we trust them?

Why are the rich thinner than the poor? Does poverty cause obesity or the other way around? The answer is both. Stigmatization links the two.

Is it really the role of government to interfere with the free market and what we eat? There is a trick to preserving choice but tipping the balance in favor of health.

Introduction

For more than 15 years I ran a private practice in Wellington whose patients included some of the citys most highly motivated and well-resourced individualslawyers, diplomats, doctors, and bankers. I am an endocrinologist and many of the patients referred to me were suffering from type 2 diabetes. Excess weight was the problem.

My patients were people used to having a high degree of control over their lives and were prepared to pay whatever money and put in whatever effort was required to manage their medical problems. Tell me what weight you want me to be, Doc, and Ill get there was a typical response. Others had spent half their lives on diets and were less optimistic about losing weight, but most were willing to give it another go. They promised to join a gym, get a dog to take walking or play more tennis, and to eat well.

At the end of the initial consultation the patient and I were both filled with purpose and optimism.

Three months later, most patients reported a drop in weight, an improvement in blood sugar levels, and an overall feeling of increased health and energy. We celebrated the changes and looked forward to more.

Sometimes things kept going well. But more often my patients weight started to creep up again. By 12 months most had started to regain weight and some just stopped showing up at the clinic, ashamed of their failure. By two years almost all had returned to their original weight.

What happened next? A few were persuaded to have gastric bypass surgery. Others resigned themselves to the inevitable, and our focus shifted to managing the diabetes, high blood pressure, and raised cholesterol with medication.

Over the same period, I ran a diabetes clinic for teenagers. As time went on the numbers of teenagers with type 2 diabetes increased. As with adults, the key for them was to lose excess weight. They were growing children with high energy requirements so losing weight should have been easy. If you keep their energy intake to a certain level, children should become slim.

Well, maybe. One of my teenage patients was a 14-year-old girl who weighed more than 300 pounds at the time her diabetes was diagnosed. She was intelligent, engaged, and desperately keen to be slim. She wanted to avoid insulin injections, but this paled into insignificance alongside worries about self-esteem and peer pressure. We set up dietician appointments, talked about her physical activity (which was actually very highshe played a lot of sports), and moaned about her big-eating older brothers.

I scheduled follow-up appointments and she attended most of them. Astonishingly, at every appointment she was heavier than at the lasther weight increasing in parallel with her growth in height. She completed school, and by the time she finished a law degree she was on insulin therapy, anti-hypertensive drugs, and cholesterol-lowering drugs. By then we were planning gastric bypass surgery.

Television programs such as The Biggest Loser and thousands of magazine articles tell us that we can lose weight by following this new diet or adopting that exciting exercise regime. When patients came to see me in the clinic I gave them much the same advice.

But my years of experience, treating the same individuals, gradually changed my attitude. I realized that asking people to lose a significant amount of weight and keep it off was about as useful as asking them to change their eye color. No other therapeutic strategy employed in medicine has such poor results so why was I continuing to prescribe it? Not only was the treatment I was recommending ineffective but it was my patient who was invariably left with the sense of failure. Inducing a sense of guilt or hopelessness doesnt fit with my understanding of the Hippocratic Oath. So, years ago, I made the decision to stop asking patients to lose weight.

This book is for the people (and their spouses, their children, their parents, and their doctors too) who try to lose weight but fail. Its for the overweight people who think its all their fault. If we really want to tackle the problems that come with obesity we first need to understand why most of us cant change our body size. In their responsibility with regard to the obesity epidemic extends no further than providing choice. And it suits governments, who like to avoid putting in place regulations that restrict the free market. But, as we will learn, the drivers of obesity lie outside the control of individuals.