ContentsAn introductionby Ben Machell If someone asked you to describe your favorite childhood toys, the chances are you would not have to think too hard about it. So many early memories become hazy and indistinct over time, but precise details of the toys we loved somehow endure: the specific smell of a stuffed bunny rabbit; the thrill of gripping the hilt of a plastic sword; the sound and feel of your small hand rummaging through a large box of LEGO bricks. Toys are the first things over which we feel any real ownership, and as children, we cared about them more ferociously than we would probably like to admit now. On one level, this is why Gabriele Galimbertis work is so affecting. Few subjects could be more inclusive than toys and childhood. All that the viewer requires to appreciate these photographs are empathy and memory.

ContentsAn introductionby Ben Machell If someone asked you to describe your favorite childhood toys, the chances are you would not have to think too hard about it. So many early memories become hazy and indistinct over time, but precise details of the toys we loved somehow endure: the specific smell of a stuffed bunny rabbit; the thrill of gripping the hilt of a plastic sword; the sound and feel of your small hand rummaging through a large box of LEGO bricks. Toys are the first things over which we feel any real ownership, and as children, we cared about them more ferociously than we would probably like to admit now. On one level, this is why Gabriele Galimbertis work is so affecting. Few subjects could be more inclusive than toys and childhood. All that the viewer requires to appreciate these photographs are empathy and memory.

In some ways, it is a very simple project, Galimberti explains. You dont necessarily need to know all about the history of photography, or have an in-depth understanding of different photographic techniques, in order to appreciate the images. My eighty-five-year-old grandmother doesnt know where some of the countries I visited areplaces like Zambia, Malawi, or Fijibut she remembers her favorite toys. Everybody does. Galimbertis journey around the world photographing children and their toys lasted thirty months and took him to fifty-eight countries. The project began, however, just a few miles from his home in Castiglion Fiorentino, Tuscany.

Commissioned to provide a portrait of a typical Tuscan child, he drove to a nearby farm to photograph four-year-old Alessia, who had been playing with an array of colorful plastic farming implements. I decided to lay out the toys on the ground in front of her, says Galimberti. Immediately, there was something about the composition I liked. As work took him around the worldfrom Alaska to Haiti, Fiji, Australia, Southeast Asia, India, Europe, Africa, and, finally, South AmericaGalimberti repeated this composition over and over. For every photograph, I would spend the entire day with the family. In some places, like China and the Middle East, the parents would push their children hard to pose for the photos, even if the kids didnt seem comfortable.

It could be a bit embarrassing. I didnt want to take pictures of crying children. Elsewhere, in places like South America, the parents seemed relaxed to the point of ambivalence. They said I could do whatever I wanted, provided their children didnt mind. Time and again, Galimberti was struck by how the toys presented to him revealed something about the economic and social reality in which the children lived. While young Tuscan farm girl Alessia played with plastic farm tools, one child from an affluent family in a booming Chinese city loved playing Monopoly.

Four-year-old Abel Sientes Armas from Nopaltepec, Mexico, lived near a major sugar cane plantation, and grew up seeing endless convoys of big trucks rumbling down his road. His favorite toys? Big trucks, arranged for Galimberti in an endless circular convoy. These toys, Galimberti began to realize, said as much about the mothers and fathers as they did about the children themselves. I learned more about being a parent than I did about being a child from this whole process, he says. Hopes and ambitions are passed down through the toys parents choose for their children. Children from families boasting musicians invariably receive toy instruments.

Ralf, from Riga in Latvia, had countless toy cars bestowed on him by his taxi-driver mother, who named him after racing driver Ralf Schumacher. She loves cars. Now he does, too. However, this dynamic only applied in countries where parents could pick and choose which toys their children could have. In areas of poverty, the difference was striking. I ended up in a small village in northern Zambia where there was nothing.

No electricity, no water, and, of course, no toy shops. But the children had found a box of sunglassesI think it fell off a truckand the glasses became their favorite toys. Actually, their only toys. They would play market, buying and selling the glasses to each other, sharing everything between them. Again, this reflected a broader pattern. The fewer toys a child had, the less possessive he or she was about them.

Galimberti describes having to spend several hours winning the trust of Western children before they would consent to let him touch their planes, cars, or dolls. In poorer countries, they dont careas much. They play in a different way, running around, sharing one ball between them all. Likewise, children who enjoy a free-roaming existence in the countryside seemed to place less value on their toys than children living in busy cities, confined and isolated. City children mostly stay inside, and mostly play alone, he says. They tend to have a lot more toys and to be a lot more possessive.

Still, there were occasions when touching coincidences would exist between children living thousands of miles apart. In the United States, a boy named Orly loved plastic dinosaurs. In Malawi, a boy named Chiwa loved a plastic dinosaur too, a green triceratops given to him by an NGO worker. They both maintained that their dinosaurs protected them at nightin Orlys case, from the threat of kidnappers; in Chiwas case, from dangerous animals and venomous insects. Galimberti says that, more than anything, this project was funa simple and heartfelt conclusion to a simple and heartfelt project. Ben Machell is a feature writer for The Times of London. Ben Machell is a feature writer for The Times of London.

He was also a fully paid-up member of the LEGO Club as a kid. Orly, 4 Brownsville, Texas  Bethsaida, 4 Port-au-Prince, Haiti

Bethsaida, 4 Port-au-Prince, Haiti  Mikkel, 3 Bergen, Norway

Mikkel, 3 Bergen, Norway  Allenah, 4 El Nido, Philippines

Allenah, 4 El Nido, Philippines  Taha, 4 Beirut, Lebanon

Taha, 4 Beirut, Lebanon  Julia, 3 Tirana, Albania

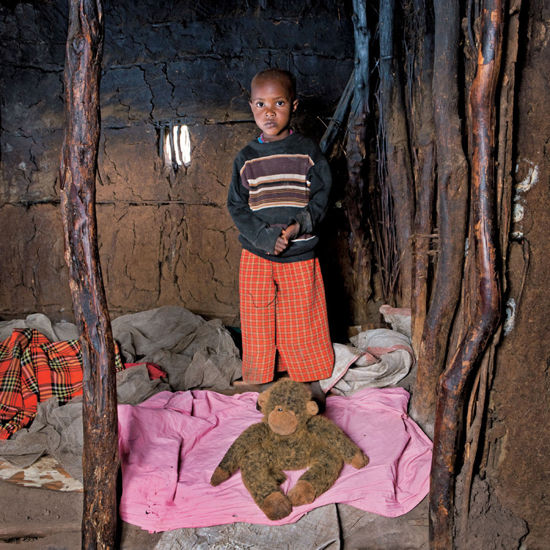

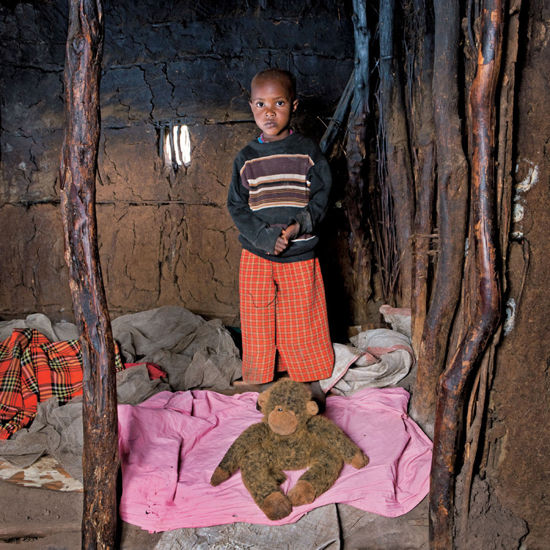

Julia, 3 Tirana, Albania  Tangawizi, 3 Keekorok, Kenya

Tangawizi, 3 Keekorok, Kenya  Cun Zi Yi, 3 Chongqing, China

Cun Zi Yi, 3 Chongqing, China  Julius, 3 Lausanne, Switzerland

Julius, 3 Lausanne, Switzerland  Arafa & Aisha, 5 Bububu, Zanzibar

Arafa & Aisha, 5 Bububu, Zanzibar  Lucas, 3

Lucas, 3

Next page

ContentsAn introductionby Ben Machell If someone asked you to describe your favorite childhood toys, the chances are you would not have to think too hard about it. So many early memories become hazy and indistinct over time, but precise details of the toys we loved somehow endure: the specific smell of a stuffed bunny rabbit; the thrill of gripping the hilt of a plastic sword; the sound and feel of your small hand rummaging through a large box of LEGO bricks. Toys are the first things over which we feel any real ownership, and as children, we cared about them more ferociously than we would probably like to admit now. On one level, this is why Gabriele Galimbertis work is so affecting. Few subjects could be more inclusive than toys and childhood. All that the viewer requires to appreciate these photographs are empathy and memory.

ContentsAn introductionby Ben Machell If someone asked you to describe your favorite childhood toys, the chances are you would not have to think too hard about it. So many early memories become hazy and indistinct over time, but precise details of the toys we loved somehow endure: the specific smell of a stuffed bunny rabbit; the thrill of gripping the hilt of a plastic sword; the sound and feel of your small hand rummaging through a large box of LEGO bricks. Toys are the first things over which we feel any real ownership, and as children, we cared about them more ferociously than we would probably like to admit now. On one level, this is why Gabriele Galimbertis work is so affecting. Few subjects could be more inclusive than toys and childhood. All that the viewer requires to appreciate these photographs are empathy and memory. Bethsaida, 4 Port-au-Prince, Haiti

Bethsaida, 4 Port-au-Prince, Haiti  Mikkel, 3 Bergen, Norway

Mikkel, 3 Bergen, Norway  Allenah, 4 El Nido, Philippines

Allenah, 4 El Nido, Philippines  Taha, 4 Beirut, Lebanon

Taha, 4 Beirut, Lebanon  Julia, 3 Tirana, Albania

Julia, 3 Tirana, Albania  Tangawizi, 3 Keekorok, Kenya

Tangawizi, 3 Keekorok, Kenya  Cun Zi Yi, 3 Chongqing, China

Cun Zi Yi, 3 Chongqing, China  Julius, 3 Lausanne, Switzerland

Julius, 3 Lausanne, Switzerland  Arafa & Aisha, 5 Bububu, Zanzibar

Arafa & Aisha, 5 Bububu, Zanzibar  Lucas, 3

Lucas, 3