LUCIFERS LEGACY

LUCIFERS LEGACY

The Meaning of Asymmetry

FRANK CLOSE

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Copyright

Copyright 2000, 2013 by Frank Close

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2013, is a revised republication of the work originally published in 2000 by Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Close, F. E.

Lucifers legacy : the meaning of asymmetry / Frank Close.

pages cm

Originally published: Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 2000.

Includes index.

eISBN 13: 978-0-486-78214-0 Symmetry (Physics) I. Title.

QC174.17.S9C56 2013

530dc23

2013014078

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

49167601 2013

www.doverpublications.com

For Katie and Lizzie: the Real Legacy

Acknowledgments

A t the end of a film, the credits roll for several minutes. Someone must have kept a checklist of every person that chanced upon the set so that they can be listed alongside the codenames of theatre, such as BestBoy, Grip, and other characters that seem to have spilled over from Lewis Carroll. I regret that I have not been so efficient. Anecdotes have come from people who have asked some perceptive question or made a comment after talks that I have given and of whom I have no record. In addition, many discussions with speakers at the British Association for the Advancement of Science, or with colleagues at the European Centre for Particle Physics CERN in Geneva, and in the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory are too numerous to mention other than collectively.

However, among these there are a few that I would like to acknowledge specifically. Talks on symmetry by Denys Wilkinson, Ian Stewart, and Chris Llewellyn Smith stimulated my interest in this area; I enjoyed meeting with Henning Genz and sharing ideas on how to popularise the Higgs mechanism and I am also indebted to Peter Higgs for copies of his original manuscripts and anecdotes. Peter Kalmus insights in his talk on the Forces of Nature also deserve mention as do the help I received from Lewis Wolpert, Chris McManus, Steve Laval, Dahlia Zaidel, Charles Stirling, Peter Watson, and Ken Zetie on the bizarre role of mirror asymmetries in atoms, chemistry, and living organisms. Neil Calder, Mick Draper, and Rolf Landua at CERN and Bryson Gore at the Royal Institution have helped in providing some of the conceptual illustrations and Tim Radford and David Newnham at The Guardian have helped my thoughts on antimatter to mature. Good editors are essential and I am indebted to Carole Sunderland, and also to Susan Harrison and Beth Knight, at Oxford University Press, for their role in bringing Lucifers Legacy to life.

Contents

Chapter 1

Lucifer

Headless body found in topless bar

(USA newspaper headline)

T he world is an asymmetrical place full of asymmetrical beings. If the Creation had been perfect, and its symmetry had remained unblemished, nothing that we now know would ever have been. There would have been no you to read this book, nor me to have written it; there would have been no Paris in the spring, and no Tuileries Gardens. So I would not have come across the headless bodythe chance event that started me wondering on the accident, or design, that has created life out of arid equations.

Lest you make this for a seamy pot-boiler, or even Hercule Poirotstyle murder mystery, I should make clear at the outset that the body in question was made of stone, its head lying in the gravel at the base of a plinth which bore the legend Lucifer. Had it been other than in the Tuileries I would probably have passed by without giving a second glance, but the gardens are beautiful, laid out with mathematical precision. I paused and looked again at headless Lucifer. Its disfigured presence in the midst of an otherwise all pervading perfection was as profound as the unresolved chord that ends Bachs St Matthew Passion and seemed like a metaphor for existence.

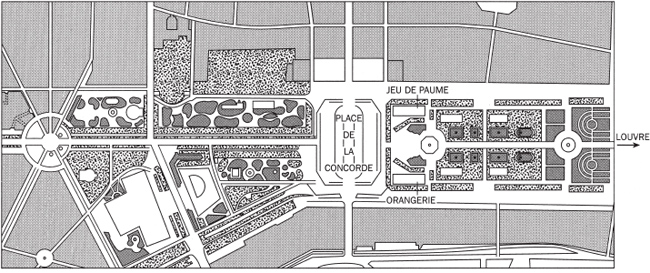

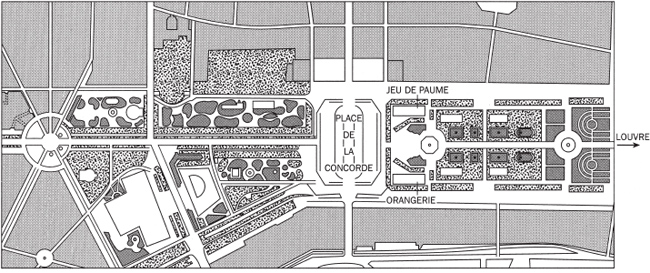

The spring day had started slowly as I had come to Paris by train from London. The carriages had meandered through southern England, as if to give the passengers time to appreciate the picture postcard views of Kent, before speeding through the featureless landscapes of northern France, impatient for the graceful architecture of Paris, among which is one of the most remarkable perspectives in Europe. From the midpoint of the Arc de Triomphe the line of sight along the Champs Elyses leads first to the obelisk at the centre of the Place de la Concorde and then runs the length of the Tuileries Gardens to the open arms of the Louvre. Where this line passes through the Tuileries it has been used like a mirror such that with draughtsmanlike precision the two halves of the gardens are perfect reflections of one another ().

To experience the symmetry to the full, first stand at the western end in the Place de la Concorde looking in the direction of the Louvre at the far end of the Tuileries. Within the park and a hundred metres to your right is the Orangerie, a hothouse erected by Napoleon III and now used for art shows; its mirror image, the same distance on your left, is the Muse du Jeu de Paume, Napoleons tennis court. Identical mirrored paths connect the two buildings to your position at the parks entrance. On your immediate left you will see a high stone wall, curved with its concave side towards you; to the right of you is another wall, its arc a perfect mirror of its partner. The pair are a miniature imitation of the curved collonades that caress your arrival before the entrance of St Peters in Rome. Whereas statues of angels decorate Michaelangelos creation, the entrance to the Tuileries holds sinister statues of philosophers, gods, and dead Frenchmen in its embrace; to your left and to your right the guardians stand in perfect symmetry. The effect though is similar. The pair of symmetric concave curves are like a mothers arms taking her child; they welcome and encourage you to enter within.

The central avenue leads proudly from the far side of the curve, diametrically opposite you. This gravel carriageway defines the axis of the imaginary mirror, identical trees and flower-beds bordering it to left and right. Were you to rest briefly on one of the benches alongside the path and survey the beauty of the gardens, you would find the view obscured by a corresponding bench across the way. To every statue on one side there is a statue on the other, to every tree a tree, to every flower garden on the north side there is another planted at the same distance to the south. A water fountain sprays from the mouth of a nymph who is gazing soulfully at its clone, forever separated by twice the distance to the centre line of the park.

Fig. 1.1 Map of the Tuileries Gardens

And so it went on until I saw the headless devil twenty metres down a side path. I knew that behind me, as yet unseen, would be a mirror image of this path that would lead to a correspondingly positioned plinth and fiendish statue. I half expected that this too would be broken, so preserving the symmetry of the park, but when I turned and looked I saw that its diabolic twin grinned from its plinth as it had done since its creation. In the entire gardens the designer symmetry was perfect with the sole exception of headless Lucifer.

The symmetry of the Tuileries Gardens and its interruption by the disfigured devil are metaphors for our grander perceptions of the natural world. Symmetry is fascinating and appealing; scientists seek it in their data and incorporate it in their theories, ironically even when there is no immediate evidence for it. Perhaps the most arcane example of this concerns the nature of matter and the fabric of existence embodied in the current cosmophysical description of Creation.

Next page