Introduction: modern gardening in an historic landscape

Gardening at the National Trust: Forever for Everyone

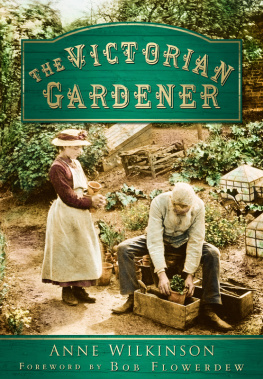

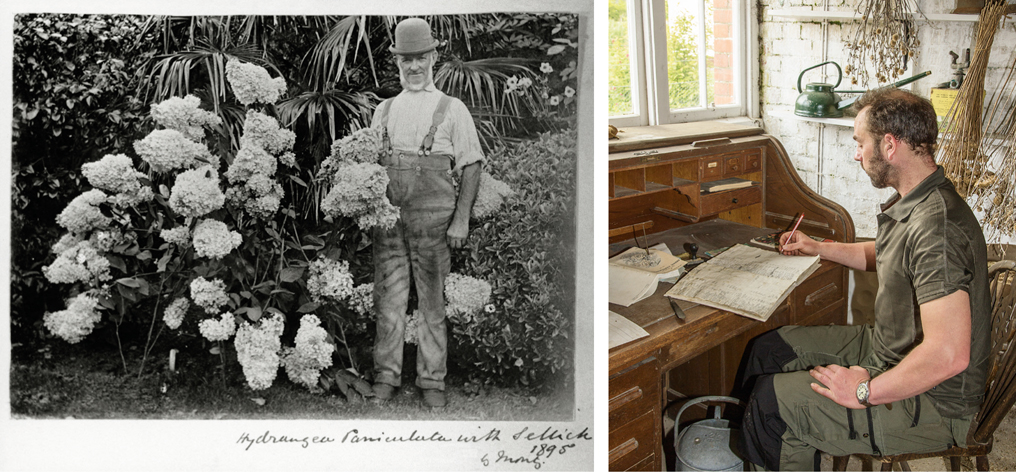

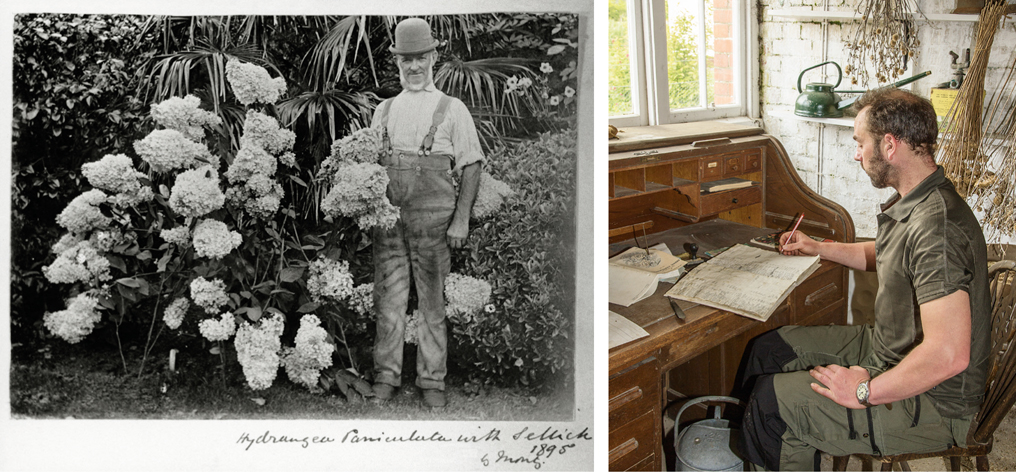

Above Left Sellick, the Head Gardener at Saltram, Devon, in 1895 stands in front of his hydrangeas.

Above Right The author at the desk in the Head Gardeners office at Polesden Lacey, Surrey.

I sit writing this in the Edwardian Head Gardeners office at Polesden Lacey, adjoining the potting and tool sheds at the back of the walled garden. It is 7.20 in the morning and I am waiting for the team of gardeners to turn up for the day. Many of the original tools used more than 100 years ago still hang on the walls and racks that surround me. Copies of old seed catalogues and planting diaries dating back to this period are filed in the drawers behind me for posterity. The shelves by my head are stacked with terracotta pots, placed in order of size, ready for the gardeners to sow into, and the original soil sieves sit out on the potting bench. Stepping into the office each morning is a sensory overload as the evocative musty smell of compost and damp crocks mingles with whatever plants are flowering in the window display of the potting shed. Today there are hyacinths and miniature narcissus perfuming the fresh, cool air. A shard of light from the early spring sunshine is thrown across the tiled floor from from the door, which has been left ajar. I feel a cool breeze on my face and I catch a sweet-smelling waft of Christmas box (Sarcococca humilis), flowering just outside the door.

On the face of it, very little has changed in the world of gardening over the last few centuries. I can imagine that a past head gardener would have walked into this very office 100 years ago, sat down in the same chair and written up a list of jobs for the day almost identical to the one I wrote earlier. They would have looked out of the window at a scene very similar to the one I see today. He too would have seen the frame yard where vegetables are being forced on under glass for taking up to the house for guests to enjoy. The main difference today is that the guests are not part of the aristocracy, but National Trust visitors and members who have come to enjoy and be inspired by the gardens.

Of course there have been many changes in the world of gardening, such as the mechanisation of equipment and the development of disease-resistant plants and varieties with better fruiting or flowering qualities. Accepted standards on the best techniques of how to plant and prune have also changed substantially, as have methods of propagation and the feeding of plants. National Trust gardeners have always been at the forefront of the latest gardening practices, and the gardens they look after have thrived from it.

However, despite these technical advances, there is a gradual change which in some cases is almost bringing us full circle, back to the heyday of the great British gardens and landscapes. Driven by a desire for long-term sustainability, gardeners are rediscovering the rustic skills of their forefathers and reviving many lost gardening techniques. Petrol-driven strimmers are being traded in for scythes, and rotavators swapped for spades. Modern gardeners now prefer to use homemade comfrey or nettle tea rather than artificial fertilisers and to adapt green methods for managing pests and diseases rather than reaching for a chemical treatment. Wildflower meadows are once again flourishing and a richer biodiversity of the planet is something to be enjoyed and celebrated rather than looked on with suspicion. Fuel-guzzling garden mowers are being switched off while we enjoy longer grass instead of perfectly manicured lawns. Suddenly gardeners are once again in love with nature and no longer at war with it.

Awareness of the environment and the importance of the conservation of places of historic significance is the key driver to these changes. A long-term vision of a sustainable future is the core principle to a greener world. Minimal intervention and working with nature as opposed to working against it is now very much the principle underpinning the work of contemporary gardeners.

The biggest growth area in modern gardening is without doubt the revival in growing your own food. Not since the Dig for Victory war campaigns has there been such a wish to reconnect with the soil and produce homegrown food like our ancestors would have done on the allotments or in their gardens. In twenty-first-century gardens the desire to reconnect with other like-minded gardeners is evident as more community kitchen gardens appear on National Trust land than ever before.

Sustainability and supporting a rich biodiversity

The symbol of the National Trust is the oak leaf, probably the most majestic and magnificent plant species in the country. Its mighty trunk supports weighty boughs that stretch out in all directions, almost defying the laws of gravity. Whether it is standing alone in open landscape or in a mixed woodland, it stands head and shoulders above other trees and plants. It epitomises strength, standing upright and proud, ready to face any adversity. Chances are it will still be standing there still in hundreds of years. Over the centuries it will see the landscape around it evolve and will adapt to it. From its lofty heights it will witness gardening styles and fashions change around its mighty girth. It will support a rich biodiversity teeming with wildlife, supporting a rich community, whether it is birds nesting in the trees, insects living among the bark or toadstools living on the roots. And when it finally dies, it will have produced thousands of acorns which will have grown into trees for future generations to enjoy.

The National Trust is a conservation charity looking after one of the greatest collections of historic gardens and cultivated plant collections in the world. The oak tree is an apt symbol for the National Trust, which also supports a rich and diverse society, teeming with a wide range of people from all walks of life more than 4 million garden-visiting members, 1,000 modern and historic gardens, more professional gardeners than any other conservation charity in the country and thousands of garden volunteers.

Learning from our past

The gardens cared for by the National Trust stretch back more than 400 years. The charity was originally formed in 1895 and was the vision of three environmental pioneers, Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, with the intention of preserving the green spaces that were being encroached upon by the late-Victorian urban sprawl. The National Trust is now custodian to some of the most important landscapes and historic gardens in the country. Gardens such as Hidcote, Sissinghurst, Stourhead, and Bodnant are some of the most beautiful gardens not just in the UK but worldwide, with some of the most impressive plant collections and demonstrations of horticultural excellence.

The thousands of historic gardens cared for by the Trust reflect fashions, styles and social changes throughout the last few centuries. They support a diverse range of plants, as well as the wildlife that depend on them. These historic gardens are an important slice of social history, for their creators include Capability Brown, Gertrude Jekyll, Humphrey Repton, Vita Sackville-West and Graham Stuart Thomas a list which reads like a Whos Who of the worlds most influential gardeners. They probably never imagined the enduring influence they have had on gardening in the twenty-first century.

Next page