Edmund L. Epstein

introduction

James Joyce always said that

there was only room for one novel in a

man's heart (he hadn't even begun

Ulysses then) and that when one writes

more than one, it is always the same

book under different disguises

Italo Svevo; quoted in P. N. Fur

bank, ITALO SVEVO: THE MAN AND

THE WRITER (University of California

Press, 1966, P. 121)

JOYCE TACITLY ACKNOWLEDGED this was true by his preparations for writing Finnegans Wake. In his notebooks he headed various pages with the titles of his published works and under these heads wrote commentaries on himself, which he included in the Wake. Joyce, therefore, saw all of his lifework as a piece, and we can find a pattern in his creative career only by doing the same.

The pattern that emerges from such an examination is not really difficult to describe. It is a family pattern, the children growing up and maturing, frequently against the strong opposition of their elders, to the point where youth becomes mature, and maturity becomes age. It is my intention to follow the workings of this process through A Portrait to its climax in Ulysses, always referring to Finnegans Wake for corroboration and perspective.

This topic, the growth to maturity of youth, is of peculiar interest to our time, in which youth has so loudly declared its intention to take over its own destiny. This is not the first time in history that youth has knocked at the door; Joyce's work would suggest that every youth welcomes life and goes to encounter, for the millionth time, in his new secondhand clothes, the reality of experience. In the writings of Joyce we see worked out, in detail, patterns and developments which are familiar to us, both in history books and on TV news broadcasts. Even the smallest details are therethe impatience and violence of youth, the young assassins, the "davys" throwing "bombshoobs" at the flaunting big white "harses" of the father-enemy, the boys and girls sending an unmistakable message of defiance to "the old folkers," either in the form of a "Nightletter" signed by "the babes that mean too" or by obscene words chalked on walls and shouted on stages. However, the other half of the message also is applicable to the modern age the triumphant youthful assassin of the authoritarian Russian General turns into a father figure, as revealed by the careful examination of the brains trusters, as the dawn

prepares to rise; youthful anarchists grow corners and become squares just like their parents. And so the world wags on.

Special acknowledgment is made for permission to quote from the following works. From Ulysses by James Joyce. Copyright 1914, 1918 and renewed 1942, 1946 by Nora Joseph Joyce. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc. Grateful appreciation is also extended to The Bodley Head, Ltd.

From Stephen Hero by James Joyce. Copyright 1943, 1963 by New Directions Publishing Corporation, New York. Acknowledgment is also made to Jonathan Cape Ltd., as publishers, and to The Society of Authors.

From Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. Copyright 1939 by James Joyce, copyright renewed 1967 by George Joyce and Lucia Joyce. Reprinted by permission of The Viking Press, Inc. Appreciation is also extended to The Society of Authors as the literary representative of the Estate of James Joyce.

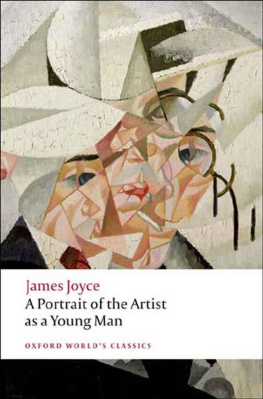

From A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce. Copyright 1916 by B. W. Huebsch, Inc., renewed 1944 by Nora Joyce. Reprinted by permission of The Viking Press, Inc. Special acknowledgment is also made to Jonathan Cape Ltd., as publishers, and to the Executors of the James Joyce Estate.

I gratefully acknowledge the care, the kindness, the patience and the many sorts of assistance I received from Professor William York Tindall during the writing of this work. I also acknowledge the assistance of Professor F. W. Dupee and Dean Kevin Sullivan, both of whom kept me on the track in different ways, and of Professor Chester Anderson, who contributed many stimulating criticisms.

I also acknowledge the assistance of my colleagues at Southern Illinois University, especially Alan M. Cohn,

-ix-

who has participated actively in the creation of this work, Charles Parish, Ted Boyle, Harry T. Moore, Clark Rodewald, John Gardner, and John Howell. Like all Joyceans, I owe a debt of gratitude to all previous workers in the field. I especially wish to acknowledge my appreciation to Father William T. Noon, S. J., for many helpful discussions in the past. Any errors, however, are mine.

I wish to acknowledge the assistance of my father, Alfred Epstein, and my mother, who were always sure that I would finish this work. Finally, I wish to acknowledge this debt, among many other debts, to my wife, Tegwen, without whom it is literally true that this book would never have been written.

E. L. Epstein

Carbondale, Illinois

March r, 1971

-x-

the ordeal of stephen dedalus

[This page intentionally left blank.] |

|

1

the conflict

of the generations

We have to had them whether we'll like

it or not. They'll have to have us now then

we're here on theirspot. Scant hope theirs

or ours to escape life's high carnage of

semperidentity by subsisting peasemeal

upon variables

FINNEGANS WAKE (P. 582, ll. 13-16)

TREATMENT of the conflict of the generations, a universal theme, is also one of the characteristic themes of modern literature. Huxley, Virginia Woolf, Lawrence, Hardy, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Dickens, Thackeray, Jane Austen, Henry James, Meredith, Conrad, George Douglas Brown, Synge, Yeatsall of those and many more wrestle with the problem of the conflict of the generations, in realistic or symbolic form. Joyce, however, is unique among the masters of modern literature in his treatment of the father-son conflict. As I hope to show, he is both milder in actual detail and more extreme in principle than any other modern writer.