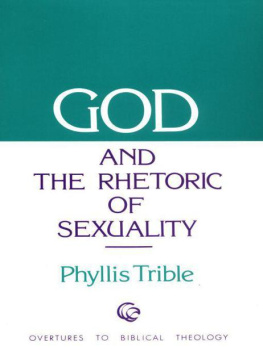

OVERTURES TO BIBLICAL THEOLOGY

The Land

by Walter Brueggemann

God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality

by Phyllis Trible

Texts of Terror

by Phyllis Trible

The Suffering of God

by Terence E. Fretheim

A Theology of the Cross

by Charles B. Cousar

Prayer in the Hebrew Bible

by Samuel E. Balentine

The Collapse of History

by Leo G. Perdue

Canon and Theology

by Rolf Rendtorff

Deuteronomy and the Death of Moses

by Dennis T. Olson

Ministry in the New Testament

by David L. Bartlett

From Creation to New Creation

by Bernhard W. Anderson

Prayer in the New Testament

by Oscar Cullmann

The Land Is Mine

by Norman C. Habel

Battered Love

by Renita C. Weems

Missing Persons and Mistaken Identities

by Phyllis A. Bird

Editors

WALTER BRUEGGEMANN, McPheeters Professor of Old Testament, Columbia Theological Seminary, Decatur, Georgia

JOHN R. DONAHUE, S. J., Professor of New Testament, Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley, California

SHARYN DOWD, Professor of New Testament, Lexington Theological Seminary, Lexington, Kentucky

CHRISTOPHER R. SEITZ, Associate Professor of Old Testament, Yale Divinity School, New Haven, Connecticut

Literary-Feminist

Readings

of

Biblical

Narratives

PHYLLIS TRIBLE

in memoriam

HELEN PRICE

MARY A. TULLY

Contents

ix

xi

xiii

Introduction:

1. Hagar:

2. Tamar:

3. An Unnamed Woman:

4. The Daughter of Jephthah:

Editor's Foreword

In her first book in this series, God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality (1978), Phyllis Trible offered a fresh way to listen to the text that permitted the text to have its own say, without excessive interpretive manipulation. By the time of this present book, Professor Trible has become established as one of the most effective practitioners of rhetorical criticism, and as perhaps the decisive voice in feminist exposition of biblical literature.

The studies offered in this book are the substance of her Beecher Lectures at Yale. That lecture series is intended to deal with the preaching enterprise in the church. Trible's perspective on exposition and proclamation is implicit and by example, without direct comment. She proposes to get the interpreter/expositor out of the way so that the unhindered text and the listening community can directly face each other.

What strikes me most about these expositions is the remarkable congruity between method and substance. That congruity has been a continuing agenda of scholarship, for we have become increasingly aware that conventional methods are essentially alien to the matter of the text and are something of an imposition on the text. The method utilized here makes very little, if any, imposition on the text. Trible presents a "state of the art" treatment of rhetorical criticism, learned from our common teacher James Muilenburg. It is hard to imagine the ground gained in the few years since he called for this methodological accent. Indeed, such a perspective was scarcely in purview in Old Testament studies when this series began. The remarkable fact about Trible's use of the method is that while she is fully conversant with literary theory, her presentation is free of every theoretical encumbrance.

But of course this book is not an exercise in method. It is the substance of the argument that makes the difference. The method, when utilized with fresh questions, lets us notice in the text the terror, violence, and pathos that more conventional methods have missed. Indeed this work makes clear how much the regnant methods, for all their claims of "objectivity," have indeed served the ideological ends of "the ruling class." What now surfaces is the history, consciousness, and cry of the victim, who in each case is shown to be a character of worth and dignity in the narrative. Heretofore, each has been regarded as simply an incidental prop for a drama about other matters. So Trible's "close reading" helps us notice. The presumed prop turns out to be a character of genuine interest, warranting our attention. And we are left to ask why our methods have reduced such characters, so that they have been lost to the story.

No doubt the feminist project of interpretation is much needed. The merit of Trible's feminist enterprise is that there is no special pleading, no stacking of the cards, no shrillness, no insistence. There is only the powerful, painful disclosure to us of what is there, so that the pain and shame have their undeniable say with us. Fittingly the method for such a reading is not pretentious or assertive. The outcome is not finally establishment of a method or pleading for a social ideology, but an insistence on the very character of the text. As our conventional methods have caused us to gloss over these victims, so this method causes us to notice the victim as an important presence. No doubt the method serves the cunning of the narrator who makes a statement that the censors of the establishment eagerly and readily fail to notice. The mark of this exposition is that it permits us to see what the text in fact speaks. And what the text in fact speaks is that hurt and terror are real and serious and cannot be excluded from the reading of any "true" story.

One other feature of Trible's work warrants attention. She is articulate, with a sure sense of what words do and how they sound and where they should be placed. The method of rhetorical criticism presumes that nothing is accidental but every word is intentional in its place. That is how it is with Trible's own words, as well as those of the text. Such sensitivity and care do honor to the preaching tradition of Beecher, which knows that words matter. And James Muilenburg would have endorsed this accomplishment as "felicitous."

WALTER BRUEGGEMANN

Abbreviations