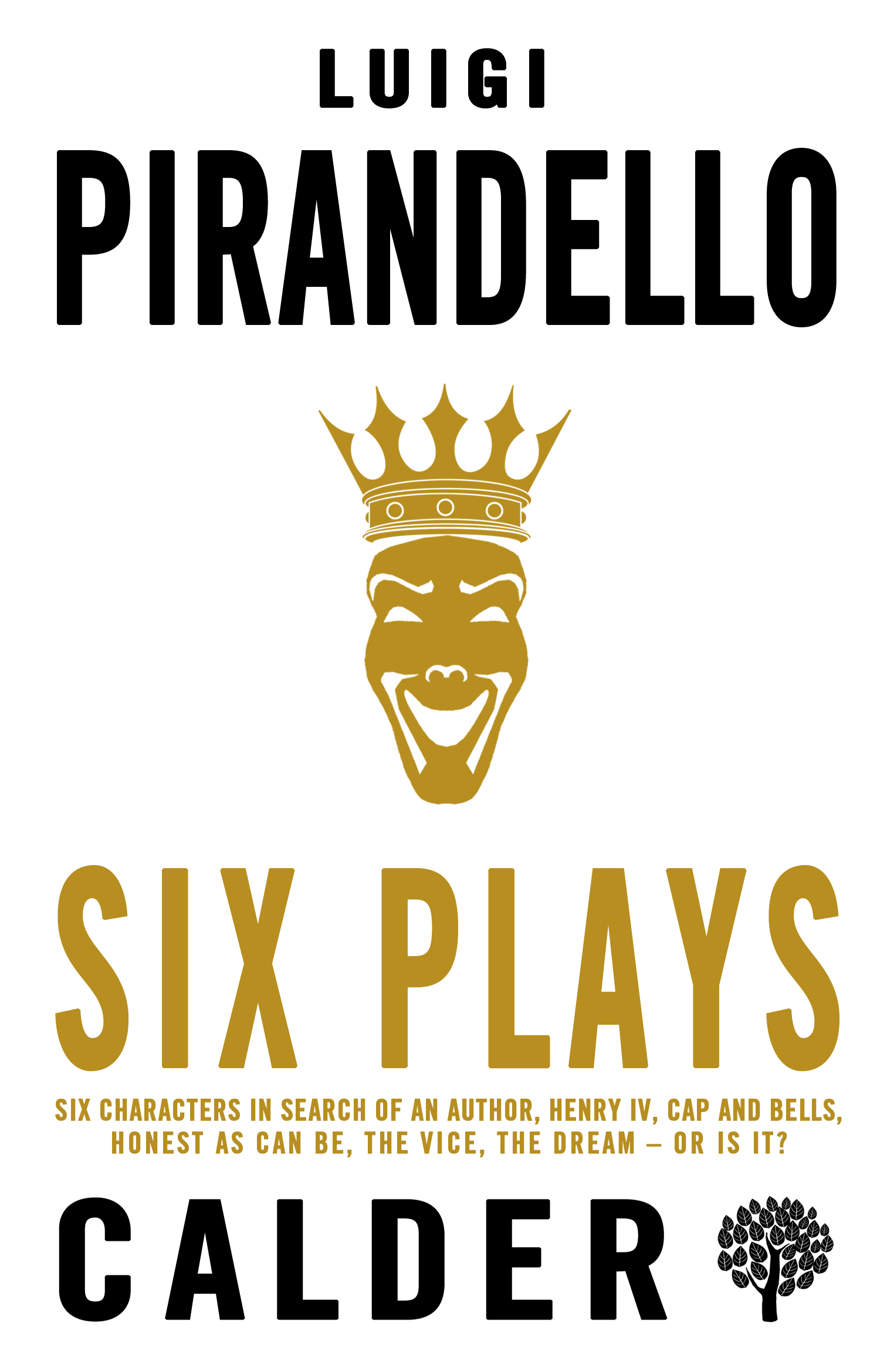

Six Plays

Luigi Pirandello

Translated by Felicity Firth,

Robert Rietti, John Wardle, Donald Watson

and Carlo Ardito

calder publications

Castle Yard

Richmond

Surrey TW10 6TF

United Kingdom

The translations of Six Characters in Search of an Author, Henry IV (revised for the present edition), Caps and Bells, Honest as Can Be, The Vice and A Dream or Is It first published in Collected Plays (Vols. 14) by John Calder (Publishers) Ltd, 19871996, and reprinted in Plays Vol. 1 by Alma Classics (2011, repr. 2015).

This edition first published by Calder Publications in 2019

Translations the relevant translators, 2019

Cover design by Will Dady

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

isbn : 978-0-7145-4849-4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Contents

Six Plays

Six Characters in Search of an Author

Sei personaggi in cerca dautore (1921)

Translated by Felicity Firth

Authors Introduction

F or a great many years now, though it seems no time at all, I have been assisted in my artistic labours by a sprightly young helpmate, whose work remains as fresh today as when she first entered my service.

Her name is Imagination.

There is something malicious and subversive about her, as her preference for dressing in black might suggest; indeed, her style is generally felt to be bizarre. What people are less ready to believe is that in everything she does there is a seriousness of purpose and an unvarying method. She delves into her pocket and brings out a jesters jingling cap, rams it onto her flaming coxcomb of a head and is gone. She is off to somewhere different every day. Her great delight is to search out the worlds unhappiest people and to bring them home for me to turn into stories and novels and plays; men, women and children who have got themselves into every conceivable kind of fix, whose plans have miscarried and whose hopes have been betrayed; people, in fact, who are often very disturbing to deal with.

Well, some years ago, this assistant, this Imagination of mine, had the regrettable inspiration, or it could have been the ill-fated whim, to bring to my door an entire family; where or how she got hold of them I have no idea, but she reckoned that their story would furnish me with a subject for a magnificent novel.

I found myself confronted by a man of about fifty, wearing a dark jacket and light trousers, grim-visaged, with a look of irritability and humiliation in his eyes. With him was a poor woman in widows weeds holding two children by the hand, a four-year-old girl on one side and a boy of not much more than ten on the other. Next came a rather loud and immodest young woman, also in black, which in her case contrived to look vulgarly dressy and suggestive. She was a-quiver with a brittle, biting anger, clearly directed against the mortified old man and against a youth of about twenty who stood detached from the others, wrapped up in himself, apparently contemptuous of the whole party. So here they were, the Six Characters, just as they appear on the stage at the beginning of the play. And they set about telling me the whole sad series of events, partly in turns, but often speaking all together, cutting in on each other, shouting each other down. They yelled their explanations at me, flung their unruly passions in my face, just as they do in the play with the luckless Producer.

Can any author ever explain how or why a character came to be born in his imagination? The mystery of artistic creation is the mystery of birth itself. A woman in love may desire to become a mother, but this desire by itself, however intense, will not make her one. One fine day she finds she is to be a mother, but she has no precise indication of when this came about. In the same way an artist, as he lives, takes into himself numerous germs of life, and he, too, is completely unable to say how or why at a given moment one of these vital germs gets lodged in his imagination to become in just the same way a living creature, though on a higher plane of life, above the vicissitudes of everyday existence.

I can only say that, having in no way searched them out, I found myself confronted by six living, palpable, audibly breathing human beings: the same six characters you now see upon the stage. They stood before me waiting, each one nursing his own particular torment, bound together by the mode of their birth and the intertwining of their fortunes, waiting for me to usher them into the world of art and make of their persons, their passions and their adventures a novel or drama, or at least a short story.

They had been born alive and they were asking to live.

Now I have to explain that for me as a writer it has never been enough to portray a man or a woman, however individual or exceptional, just for the sake of portraying them; happy or sad, I cannot just tell a story for the sake of telling it or describe a landscape simply as a creative exercise.

There are writers, quite a lot of writers, who like doing this. It satisfies them, and they ask no more. They are by nature what one might properly term historical writers.

But others go further. They feel a deep-seated inward urge to concern themselves only with persons, happenings or scenes which are permeated with what one might call a particular sense of life and so with some sort of universal significance. These, properly, are philosophical writers.

I have the misfortune to belong to this second category.

I detest the kind of symbolic art where all spontaneous movement is suppressed and where the representation is reduced to mechanistic allegory; it is self-defeating and misleading; once a work is given an allegorical slant you are as good as saying that it is only to be taken as a fairy tale; in itself it contains no factual or imaginative truth; it is simply there to demonstrate some sort of moral truth. This kind of allegorical symbolism will never answer the innermost need of the philosophical writer, apart from certain occasions where a fine irony is intended, as in Ariosto for instance. Allegorical symbolism springs from conceptual thought; it is concept, recreated as image, or striving to recreate itself as image. The philosophical writer, on the other hand, is looking for value and meaning in the image itself, while allowing the image to retain its independent validity and artistic wholeness.

Now, however hard I tried, I simply could not find this kind of meaning in the six characters. Consequently I decided there was no point in bringing them to life.

I kept thinking: I have given my readers enough trouble with all my hundreds of stories; why heap more trouble upon them with the sad story of this unhappy lot?

And so thinking I put them out of my mind. Or rather, I made every effort to do so.

But one does not give birth to a character for nothing.

Creatures of my mind, those six were already living a life which was their own and mine no longer, a life I was no longer in a position to refuse them.

And so it was that, while I went on grimly determined to expunge them from my consciousness, they, who by now had almost completely broken free of their narrative context, fictional characters magically transported outside the pages of a book, were carrying on with their own lives. They would pick on certain moments of my day to appear before me in the solitude of my study, and one by one, or two at a time, they would try to entice me, suggesting various scenes I might write or describe and how to get the best out of them, or pointing out unusual aspects of their story which people might find particularly novel or interesting, and so it went on.