I am indebted to the following, who have made a contribution to the success of this book: Gilbert Dallas, MBE BSc; John Peacock and Andy Janes of Muntons; Simpsons Malt; Bairds Malt; Brulab Ltd, County Durham; Charles McMaster, MA, Scottish brewing historian; Dr Stuart Rivers; George Howell, Head Brewer, Belhaven Brewery, Dunbar; Cooper, Dave Thorton; Dr Iain Bruinvis, Amsterdam; Colin Johnson, BAcc CA; James Mackrill, Botanix (formally English Hops) Paddock Wood, Kent; National Hop Association of England; Dr Rosemary Douglass, San Francisco; Dr Keith Alexander, Oregon, USA; Keith Robson, BA; Neil Kerr, Frank Wallace; Dave Martin of Edina Home Brew, Edinburgh; Forfar Home Brew; Robert Burton, BSc PhD MBA, Production Director; Caledonian Brewery, Edinburgh; Dr Les. Howarth; Bill Cooper; Ian McInally; Derek Blackie; Stevenson & Reeves (Hydrometers) Edinburgh; Harris Filters; Ritchie Products Ltd; Youngs Home Brew; Clive Donald of Brupaks; Kelly Filmer BSc MRSC and David Johnstone BSc. F. I. Brew, for kindly reading my first draft and his help and suggestions. However, despite such input from such a notable forum, any faux pas herein are my responsibility.

Home brewing is as old as man himself. It is thought to have originated in Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, at least 7,000 years ago. In the first great civilization, Sumeria, maltsters and brewers were held in high esteem. Their beer was made from mashed bread that was strained and left to ferment by the inoculation of wild yeast. The resultant brew was flavoured with spices and dates, and sweetened with wild honey; it was considered to have had medicinal properties. The brewers had their own guild, and had certain obligations to the temples and the Gods.

With each subsequent civilization, the craft of brewing eventually spread throughout the Middle East and Europe. The British, too, have always been home brewers, and were fermenting beverages from barley in the first century AD. The monasteries were largely responsible for the continuation of brewing in Britain, and strangers were welcomed in for the night with ale and bread, the staple diet of the day. It is recorded that the monks of St Pauls Cathedral brewed 60,000 gallons (272,000ltr) per year (thats 480,000 pints!), and that the Canons had a weekly allowance of 34 pints per day!

Many noted brewing centres today owe their origins to the early monastic establishments , and many breweries still draw their liquor from wells sunk by monks centuries ago. Eventually we brewed in the home, on the farm, in alehouses, taverns, inns and colleges, and by the nineteenth century on a gigantic commercial scale. Queen Victoria summed it all up thus: Give my people plenty of beer, good beer, cheap beer, and you will have no revolution amongst them!

As the brewing industry grew, many styles of beer evolved and Scotch ales, Burton ales, bitters, India pale ales, pale ales, porters, stouts, light ales, amber ales, brown ales, mild ales and, eventually, Pilsner-style lagers satisfied the thirst of every social class. Although the craft of home brewing waxed and waned over the years, it never died out in Britain. Until 1963, home brewers were obliged to pay tax on their brews, but how successful the Inland Revenue was in collecting it, one can only guess.

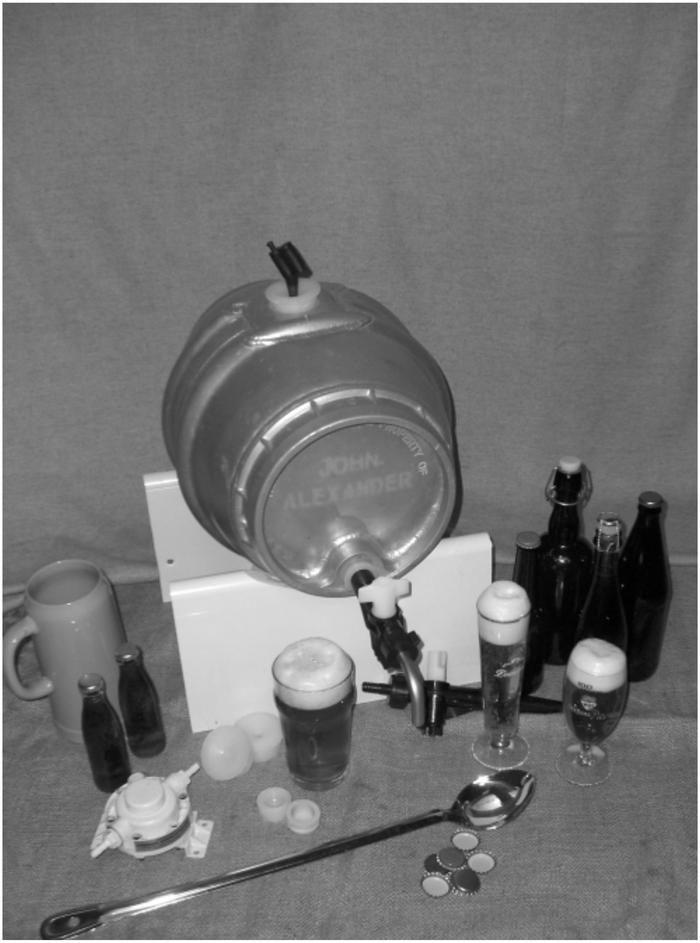

Today, the craft of home brewing is ever gaining in popularity, with a professional back-up that underpins the aspirations of the budding artisan brewer. The home brew industry has spared no effort in its desire to ensure that high quality ingredients and equipment are obtainable . The local home brew shop, too, is the bedrock of the craft, and what they dont stock, they will get for you.

There is also great interest in researching and brewing the beers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Today, craft brewers can produce any style of beer with fairly modest equipment, and yet turn out a product with the highest degree of excellence!

Traditional beer styles vary throughout the country with local and regional variations , and it is this great diversity that makes British beers so appealing.

TRADITIONAL BRITISH BEER STYLES

Burton Ale

This ale is the English equivalent of Scotch ale, and in nineteenth-century London it was offered as an alternative to Scotch ale, although many pubs sold both beers. The characteristics of Burton ale are its high gravity, OG 10701110, a very red colour, full dry-hopped flavour and an enticing aroma. Old Burton ( barley wine) was a much stronger brew, with an OG of up to 1145!

Bitter

The term historically evolved as a colloquialism in order to distinguish between highly hopped mature bitter beers and the mildness of less hopped beer. The quality of palate in todays bitters is more associated with hop character and aroma than actual bitterness, and such spicy floral fruitiness gives them their pleasing charm. Their typical profile is a straw to amber colour of 1525 EBC; an ABV of 3.54.4 per cent; and bitterness, 2035 IBUs.

Best Bitters

When brewed to full gravity, this is one of Englands finest beers. The colour may be straw to amber, the palate malty, well balanced with hop bitterness and, perhaps, a touch fruity, with a slight bitter edge. ABV 4.55.5 per cent; IBUs 2855; EBC 1530.

Light Ales

These ales are refreshing, low gravity, bottled bitter beers. They were sometimes sold as family or dinner ales, are usually pale amber in colour, with a dry hoppy finish, lively condition and good head retention. Sadly, light is rarely brewed today. Colour is 820 EBC, ABV 2.93.4, IBUs 1015.

Pale Ales

Traditionally in England, pale ales were the bottled equivalent of draught bitter. The character varies on locality due to the water, brewing tradition and local taste. The colour may be straw to rich amber, and the flavour medium malt with good hop character and aroma. Top fermenting practices might influence some estery notes in the finish. The condition should be lively with a fast-rising bead, producing good head formation and retention. Colour is 1030 EBC, ABV 4.55.5 per cent; bitterness 2040 IBUs.

India Pale Ale (IPA)

This is the illustrious colonial beer of the nineteenth century. Due to the Trent Navigation Act, Burton brewers successfully exported porter and ales to Russia and the Baltic. The strength of such beers, plus the cold northern sea routes, meant that they arrived in sound condition . After Napoleons Berlin Degree in 1806 designed to disrupt British commerce , the German and Baltic ports were no longer an option and British brewers were forced to look elsewhere.

The answer came from an unlikely source: India. To produce ale that would survive the long, hot, tortuous sea journey half way round the world, crossing the equator twice and arrive in good condition was no mean task. But as luck would have it, George Hodgsons stock pale ale was ideal: it was brewed high in alcohol and was very highly hopped, providing plenty of antiseptics. Crates of bottles and casks were stored well below the waterline, acting as ballast; this also kept the beer cool and sound as it matured during the voyage.

Here is a description of this ale, entitled That Tender Froth, from the Cornhill Magazine, March 1891:

The drinking of a glass of Basss pale ale, iced in India, in the hot weather; how it diffuses itself through you! It would produce a soul under the ribs of death. The clean, hoppy perfume. What bouquet of wine ever equalled it? And as you hold the glass lovingly up before you, what ruby or purple of what wine ever equalled that amber tint? The beaded bubbles winking at the brim of a glass of champagne, what are they compared to that tender froth?