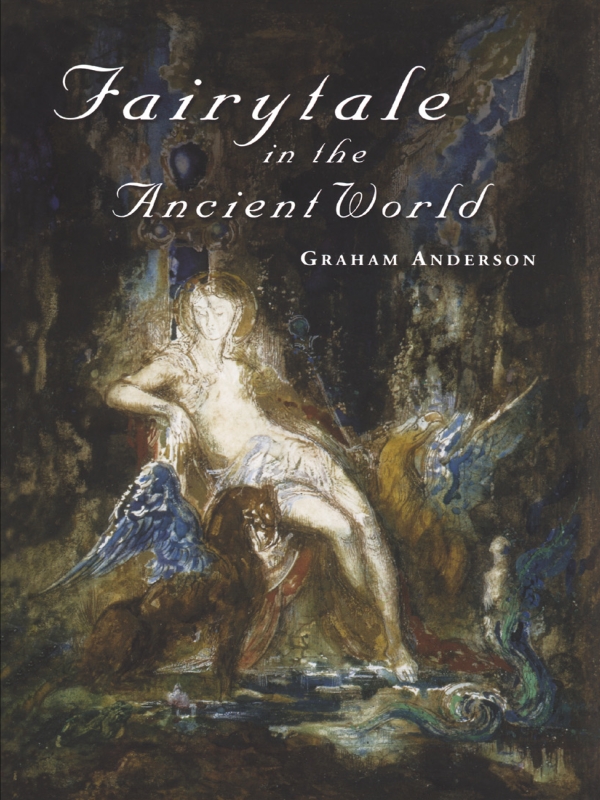

Did the familiar childrens fairytales of today exist in the Ancient World? If so, what did they look like in a world whose societies were often so alien in outlook to our own? Could fairytales have existed in a world without society balls and glass slippers, or are they an invention of storytellers not much earlier than the European Renaissance? And could they have served the same social purposes as the fairytale of today?

Graham Anderson examines texts from the classical period which resemble our Cinderellas, Snow Whites, Red Riding Hoods, Bluebeards, and others, and argues that many familiar fairytales were already well known in antiquity in some form, but are often now to be found in the least accessible corners of classical literature. Examples include a Jewish-Egyptian Cinderella, complete with ashes, whose prince is the biblical Joseph; a Snow White whose enemy is the goddess Artemis; and a Pied Piper at Troy, with King Priam in the role of the little boy who got away. He breaks new ground by putting forward many previously unsuspected candidates as classical variants of the modern fairytale, and argues that the degree of cruelty and violence exhibited in many ancient examples means that such stories must often have been destined for adults.

FAIRYTALE IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

Graham Anderson

London and New York

First published 2000

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003.

2000 Graham Anderson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Anderson, Graham.

Fairytale in the ancient world/Graham Anderson.

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

1. Mythology, Roman. 2. Mythology, Greek. 3. Fairy talesHistory and criticism. 4. Classical literatureHistory and criticism. I. Title.

BL805 .A63 2000

292.1'3dc21

00029109

ISBN 0-203-13245-9 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-203-18007-0 (Adobe eReader Format)

ISBN 0-415-23702-5 (hbk)

ISBN 0-415-23703-3 (pbk)

FOR ROGER AND AGNES CARDINAL

PREFACE

A modern collection of English fairytales begins with an attack dating from as early as 1596 against the pedants who would spend a whole day talking about the origins of Fe Fi Fo Fum. By contrast a modern Italian collector of fairytales acknowledges that there were times when he would have exchanged the whole of Proust for just one more variant of the tale he was currently collecting. These two attitudes well describe the conflict represented in searching for earlier and earlier versions of fairytales. There is horror at the triviality of it all (as there was in antiquity itself), and amazement at the mania that sooner or later takes hold of the collector. But there is a great deal more to it than that: by so much as asking whether the ancient world had a Red Riding Hood or a Rumpelstiltskin, we enter an area of cultural history which has been almost entirely forgotten or ignored.

This authors association with folktale research goes back a long way. In my first appointment I had the privilege of conversations with Sean OSullivan and Kevin Danaher, and my classical colleague Tom Williams showed me a rural hero cult in operation in County Kildare on a Sunday afternoon. It was in a classical context, working on The Golden Ass of Apuleius, that I realised that a purely literary approach left much territory unexplored, and that popular oral tales had to be taken into account. And it was in a comparative literary context, when I began to teach oral narrative and childrens literature, that once more I became conscious of the great gaps in my own knowledge of my own field of Classical Antiquity, and benefited from the immense expertise of the late Vivienne Mylne in eighteenth-century French fairytale.

I have set out to address this study to several different audiences simultaneously: to classicists, for whom, on the whole, fairytale exists only as a kind of degenerate mythology, if it exists at all; to scholars of folktale and childrens literature, for whom antiquity exists as a barrier of polite literature through which little popular material is allowed to penetrate; and to comparative literary specialists, for whom the semantics of postmodernism may often mean more than questions as simple as How old is Cinderella?. I have tried, at least some of the time, to spare those outside professional folklore circles some of the rigours of type-indexing and historic-geographic method, and have found the Opies book on fairytales a model of clarity and simplicity. But some convolution cannot be kept out of an area where evidence is so sparse and so awkwardly placed between traditionally separate disciplines. Much of the time one feels like the prince hacking away at the undergrowth that surrounds the Sleeping Beautys enchanted castle. But the delight is commensurate with the task: when the undergrowth is cleared away we have a castle full of Snow White and Cinderella, Rumpelstiltskin, and the restall in the same room. Most amazing of all: they have been lying there not for a hundred years, but in some cases for several thousand; and parts of the castle are not medieval, but built of classical columns on even earlier foundations.

It is part of the pleasure of folktale scholarship to try out versions of stories on people and watch for signs of recognition or otherwise. I have tried out materials at various times on Shirley Barlow, Tom Blagg, Ewen Bowie, Christopher Chaffin, John Court, Jim Neville, Bryan Reardon, Michael Reeve, Alex Scobie, Stephanie West, Peter Walsh and Antony Ward. I have also found classes on the traditional tale in the University of Kent a constant stimulus, particularly where mature students were able to compare the versions of tales they heard as children with those they are now encountering. Parts of the book have been delivered as lectures in the Universities of Edinburgh and St Andrews, and as a seminar in the Institute of Classical Studies in London.

I have derived much support, kindness and encouragement from Jack Zipes, and from a second anonymous Routledge reader; their suggestions have prompted an additional chapter and the relegation of some of the more complex cases to footnotes and appendices. Richard Stoneman and his staff have eased the metamorphosis of manuscript into book with an invisible magic appropriate to the subject matter. As copy-editor Mary Warren has duly performed the heroines impossible tasks.