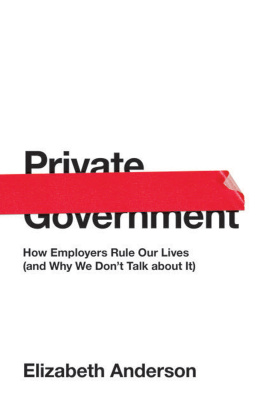

Private Government

THE UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR HUMAN VALUES SERIES

STEPHEN MACEDO, EDITOR

A list of titles in this series appears at the back of the book.

Private Government

How Employers Rule Our Lives (and Why We Dont Talk about It)

Elizabeth Anderson

Introduction by

Stephen Macedo

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket image courtesy of Shutterstock

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17651-2

Library of Congress Control Number 2017933364

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Text Pro and Helvetica Neue

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Stephen Macedo

Ann Hughes

David Bromwich

Niko Kolodny

Tyler Cowen

Elizabeth Anderson

Introduction

Stephen Macedo

The two lectures that are the centerpiece of this volume call for a radical rethinking of the relationship between private enterprise and the freedom and dignity of workers. They describein broad but vivid brushstrokesa centuries-long decline in free market progressivism. They argue that, from the time of the English Civil War, in the mid-seventeenth century, to Abraham Lincoln, two hundred years later, there were good grounds for optimism about the capacity of free markets to promote equality of status and standing. That optimism gave waywith the Industrial Revolution, and for reasons described laterto pessimism concerning rising inequality and domination in the workplace. As opportunities for self-employment declined drastically, workers had fewer alternatives to managers arbitrary and unaccountable authority. The breadth of that authority is extremely wide, leaving workers vulnerable to being fired for speech and conduct far removed from their workplaces. Todays free market thinkingamong scholars, intellectuals, and politiciansradically misconstrues the condition of most private sector workers and is blind to the degree of arbitrary and unaccountable power to which private sector workers are subject.

Just how this happened is the subject of Elizabeth Andersons important and timely Tanner Lectures on Human Values, first delivered at Princeton University in early 2014. Anderson is one of the worlds foremost political philosophers: the author of widely influential books on Values in Ethics and Economics (1993) and The Imperative of Integration (2010). Among her many articles, the pathbreaking What Is the Point of Equality? (1999) shifted the attention of social philosophers beyond a sole focus on inequalities in material distribution toward equality in social relations. Professor Andersons long-standing concerns with social equality of authority, esteem, and standing are at the center of this book.

The two lectures are followed by four pointed commentaries originally delivered, and revised for publication, by eminent scholars who draw on their expertise in history, literature, political theory, economics, and philosophy. The volume ends with Professor Andersons response to the challenges of her critics.

The remainder of this introduction offers a brief overview of each of these contributions.

In her first lecture, Elizabeth Anderson argues that free market political and economic theorynowadays associated with libertarians and the political rightoriginated as an egalitarian and progressive agenda: from the Levellers in England in the seventeenth century through the American Civil War, market society was often understood as a free society of equals. Anderson ably sketches the highlights of the free market egalitarianism of the early modern period, focusing on the Levellers, John Locke, Adam Smith, and Thomas Paine, among others. Economic liberties and free markets were opposed to social hierarchies in the economy, politics, religion, society, and the family. As she nicely summarizes:

Opposition to economic monopolies was part of a broader agenda of dismantling monopolies across all domains of social life: not just the guilds, but monopolies of church and press, monopolization of the vote by the rich, and monopolization of family power by men. Eliminate monopoly, and far more people would be able to attain personal independence and become masterless men and women.

It was only in the nineteenth century that free market thinking drifted away from its earlier egalitarian moorings. Following Paine, free market thinkers increasingly regarded the state as an abuser of power in the name of special interests. The other cause was the Industrial Revolution.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, thinkers such as the Leveller John Lilburne and the great political economist Adam Smith assumed that free men operating in free markets would be independent artisans, merchants, or participants in small-scale manufacturing enterprises. Smiths pin factorywhich illustrated the division of laborhad ten employees. Thomas Paine and the American Founders, who favored economic as well as political liberty, assumed that the bulk of the population would be self-employed. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century America free market wages were high given chronic labor shortages, and self-employment was a ready option for nearly all white men. Thus, it made sense to equate economic liberty, free markets, and independence.

Free market egalitarians of old were, moreover, far from doctrinaire libertarians in their policy proposals. Many, like Smith and Paine, advocated public education, and Paine proposed a system of universal social insurance, including old-age pensions, survivor benefits, and disability payments for families whose members could not work, as well as a universal system of stakeholder grants.

Summing up the free market egalitarianism of the seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, Anderson observes that

Smiths greatest hopethe hope shared by labor radicals from the Levellers to the Chartists, from Paine to Lincolnwas that freeing up markets would dramatically expand the ranks of the self-employed, who would exercise talent and judgment in governing their own productive activities, independent of micromanaging bosses.

The Industrial Revolution dramatically altered the assumptions upon which free market egalitarianism had rested. Economies of scale overwhelmed the economy of small proprietors, and opportunities for self-employment shrank dramatically. It dramatically widened the gulf between employers and employees in manufacturing, and, in addition, ranks within the firm multiplied.

The radical changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution for most workers, and the consequent mismatch between free market theory and reality, gave rise, says Anderson, to a symbiotic relationship between libertarianism and authoritarianism that blights our political discourse to this day.

Next page