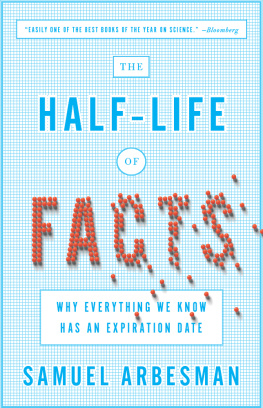

Praise for The Half-Life of Facts

An engaging bookIts a vivid account of the surprising ways in which new facts are accumulated, and how old knowledge is overturned.

Universe Today

Arbesmans enthusiasm and humor maintains our interest in subjects many readers may not have encountered before.[The Half-Life of Facts] does what popular science should doboth engages and entertains.

Kirkus Reviews

A fascinating and necessary look at the pace of human knowledge.

Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

What does it mean to live in a world drowning in facts? Consider The Half-Life of Facts the new go-to book on the evolution of science and technology.

Tyler Cowen, professor of economics, George Mason University, author of An Economist Gets Lunch

The Half-Life of Facts is fun and fascinating, filled with wide-ranging stories and subtle insights about how facts are born, dance their dance, and die. In todays world where knowledge often changes faster than we do, Sam Arbesmans new book is essential reading.

Steven Strogatz, professor of mathematics, Cornell University, author of The Joy of X

The Half-Life of Facts teaches you that it is possible, in fact, to drink from a fire hose. Samuel Arbesman, an extremely creative scientist and storyteller, explores the paradox that knowledge is tentative in particularly consistent ways. This book unravels the mystery of how we come to know the truthand how long we can be certain about it.

Nicholas A. Christakis, MD, PhD, coauthor of Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives

The Half-Life of Facts is a rollicking intellectual journey. Sam Arbesman shares his extensive knowledge with infectious enthusiasm and entertaining prose.

Michael Mauboussin, chief investment strategist, Legg Mason Capital Management, author of Think Twice

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Samuel Arbesman is an applied mathematician and network scientist. He is a Senior Scholar at the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation and a fellow at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. In addition, he writes for popular audiences as a contributing writer at Wired, and his essays about math and science have appeared in places such as The New York Times, The Atlantic, and the Ideas section of The Boston Globe.

THE

HALF-LIFE

OF

FACTS

Why Everything

We Know

Has an

Expiration Date

SAMUEL ARBESMAN

CURRENT

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Current,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 2012

This paperback edition with a new afterword published 2013

Copyright Samuel Arbesman, 2012, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this product may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Arbesman, Samuel.

The half-life of facts : why everything we know has an expiration date / Samuel Arbesman.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-1-101-59529-9

1. Evolution. 2. SciencePhilosophy. 3. Probabilities. I. Title.

Q175.32.E85A74 2012

501dc23

2012019142

Designed by Spring Hoteling

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

TO DEBRA

CHAPTER 1

The Half-life of Facts

WHEN my grandfather was in dental school in the late 1930s, he was taught state-of-the-art medical knowledge. He learned all about anatomy, many aspects of biochemistry, and cell biology. He was also taught the number of chromosomes in a human cell. The problem was, he learned that it was forty-eight. Biologists had first visualized the nuclei of human cells in 1912 and counted these forty-eight chromosomes, and it was duly entered into the textbooks. In 1953, a well-known cytologistsomeone who studies the interior of cellseven said that the diploid chromosome number of 48 in man can now be considered as an established fact.

But in 1956, Joe Hin Tjio and Albert Levan, two researchers working at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and the Cancer Chromosome Laboratory in Sweden, decided to try a recently created technique for looking at cells. After counting over and over, they nearly always got only forty-six chromosomes. Previous researchers, who Tjio and Levan spoke with after receiving their results, turned out to have been having similar problems. These other scientists had even stopped some of their work prematurely, because they could only find forty-six out of the forty-eight chromosomes that they knew had to be there. But Tjio and Levan didnt make the same assumption. Instead, they made the bold suggestion that everyone else had been using the wrong number: There are only forty-six chromosomes in a human cell.

Facts change all the time. Smoking has gone from doctor recommended to deadly. Meat used to be good for you, then bad to eat, then good again; now its a matter of opinion. The age at which women are told to get mammograms has increased. We used to think that the Earth was the center of the universe, and our planet has since been demoted. I have no idea any longer whether red wine is good for me. And to take another familial example, my father, a dermatologist, told me about a multiple-choice exam he took in medical school that included the same question two years in a row. The answer choices remained exactly the same, but one year the answer was one choice and the next year it was a different one.

Other types of facts, ones about our surroundings, also change. The average Internet connection is far faster now than it was ten years ago. The language of science has gone from Latin to German to English and is certain to change again. Humanity has progressed from a population of less than two billion to more than seven billion people in the past hundred years alone. We have gone from being earthbound to having had humans walk on the moon, and we have sent our artifacts to the boundaries of our solar system. Chess, checkers, and even