Contents

Guide

Page List

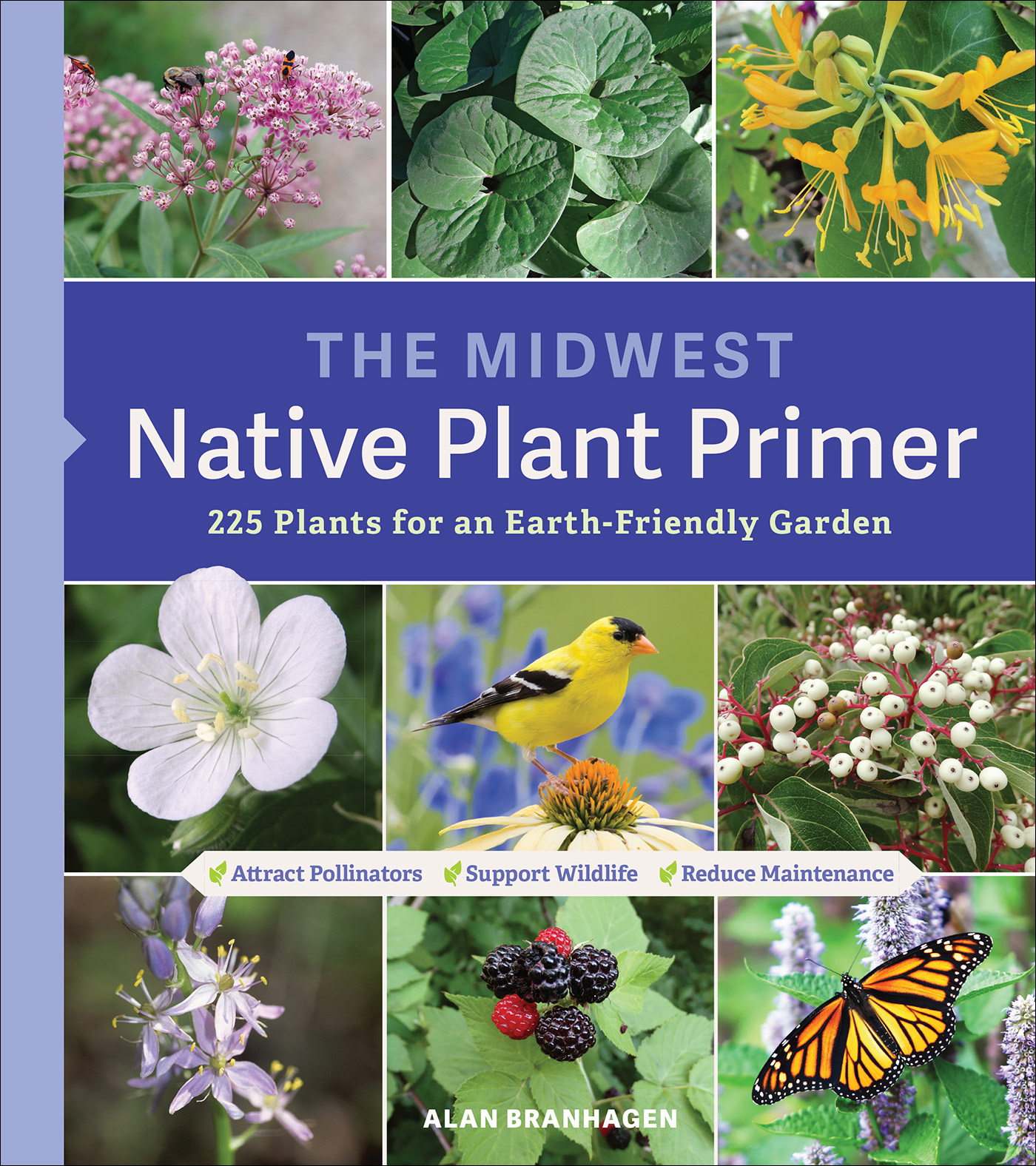

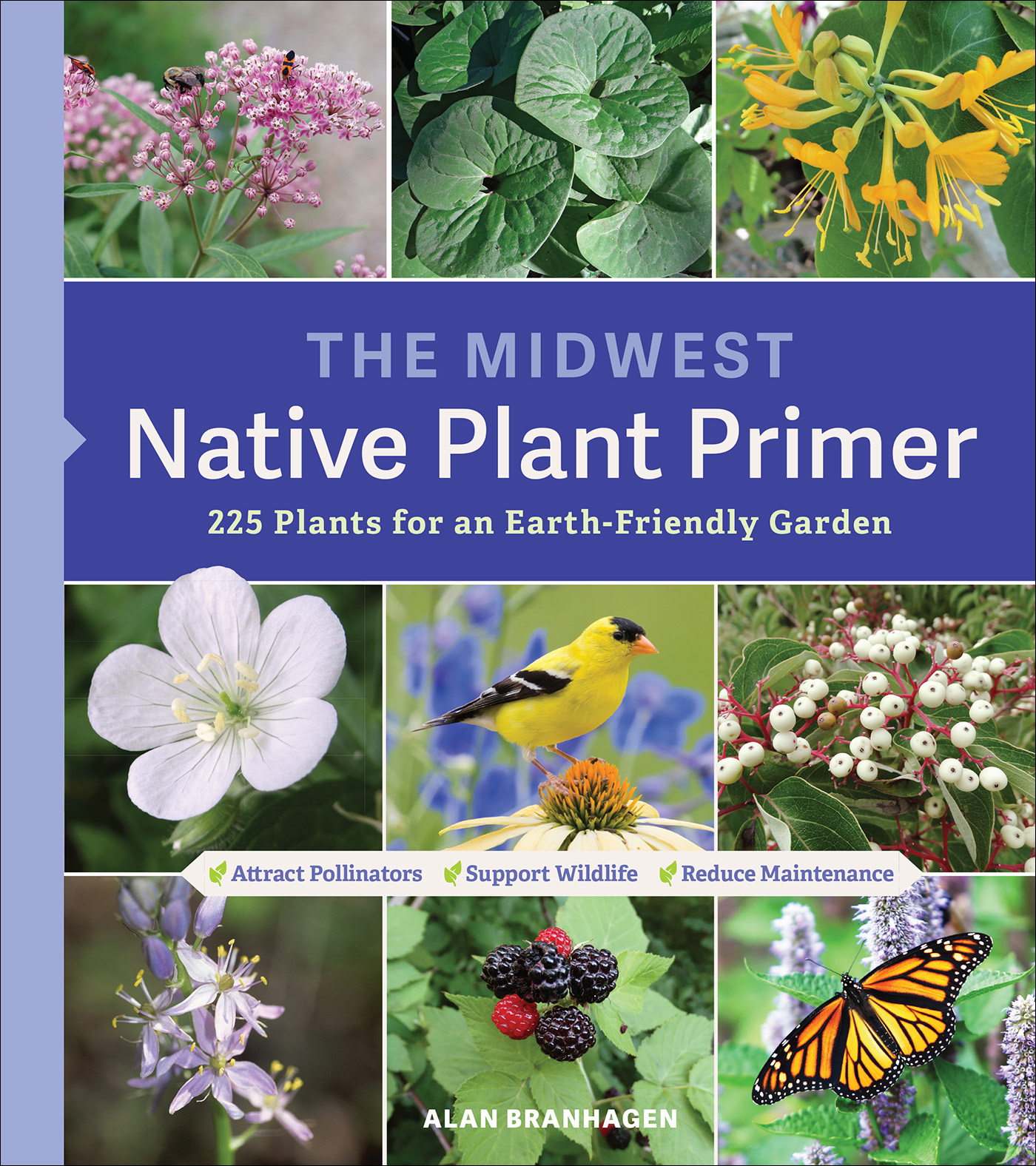

THE MIDWEST

Native Plant Primer

225 Plants for an Earth-Friendly Garden

ALAN BRANHAGEN

Timber Press

Portland, Oregon

Contents

Brilliant summer blooms of the prairie, including compass plant, pale purple coneflower, and rattlesnake master.

Introduction

IntroductionThis is a book about plants native to the heartland of North America. No place else on earth has such an extreme continental climate, yet ours is a region filled with plants of every size and in every hue. In this book, I aim to inspire readers to include native plants in their home gardens and landscapes, as well as to teach home gardeners how and where to grow these Midwest natives successfully.

Humans have manipulated the landscapes of the Midwest for millennia. Long before the first English-speaking settlers arrived, grasslands had periodically advanced eastward and northward through periods of heat and drought, the habitat they required maintained by natural and man-made fires that burned a mosaic through entire landscapes. The earliest settlers described a forest that stretched from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. Much of the forest was portrayed as open woodland, with a parklike appearance of scrub and gnarly trees interspersed with grass. The prairies were celebrated as a sea of grass so vast, it stretched to the horizon. Plants filled every niche, segregated by their adaptations to various conditions, from wet to dry, muck to sand, sun to shade, and hot to cool microclimates. We like to think of these early descriptions as depicting a pristine place, but we know that the bison, elk, and other creatures along with Native Americans and their use of fire created that landscape.

Today the seas of prairies are a vast expanse of farmland, and the forest has been fragmented into smaller tracts. Open woodlands and savannas are now dense forests. The regions great herbivores no longer roam; wildfires no longer burn. Some imported plants like bush honeysuckles and reed canary grass have usurped indigenous plants in remnant wildlands. With the forces that shaped the original landscape now gone, the remaining natural areas must be managed almost like gardens to protect their inhabitants.

Native plants are important because they sustain all life in this landscape. Many animals, mainly insects, through millennia of adaptations and evolution, are viscerally linked to a specific plant; for example, the zebra swallowtail can survive only where its host, the pawpaw, grows. We know a healthy environment for humans includes a diversity of life around us. Aldo Leopolds famous words still hold true: To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering. By including native plants in our home landscapes, we are helping to save this diversity, which is especially important in the Midwests manipulated and fragmented natural landscape.

The typical suburban landscape includes a home with foundation plantings, a lawn, and some token trees and ornamental plantings. In many cases, the shade trees are native, but most of the smaller trees, shrubs, and groundcovers, including turf, are not. And where are our native wildflowers? We can do better.

What Is a Midwest Native Plant?

In North America, a native plant is typically defined as one that grew wild in a particular or defined area prior to settlement by Europeans. And what defines our particular region, the Midwest? Its the central hardwood forest and tallgrass prairie bioregions that comprise the core of the midwestern states and a bit into Canada. Thus, Midwest native plants are those that originally grew in the hardwood forests, prairies, and associated wetlands that so beautifully interface here in the heartland of North America.

Native plants and wildflowers are not necessarily the same. A wildflower can be any plant that flourishes in a particular area on its own, including those that have naturalized from foreign shores, usually aided by humans, to reach a new region. Queen Annes lace (Daucus carota), chicory (Cichorium intybus), and oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) are examples of widespread midwestern wildflowers that are native to Europeand so are not Midwest native plants.

Ranges of all plants are dynamic, not static, and that creates a challenge when drawing boundaries. Recently, Arkansas native plants have crossed the border north into Missouri, whether from human aid or dispersed by birds and other wild creatures. Botanists have documented an increasing number of site collections in Missouri of trumpet honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens), American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana), and cedar elm (Ulmus crassifolia). The changing range of plants is ongoing and happening everywhere.

Land use, climate, and soils determine the range of native plants through time. Prior to settlement of the Midwest, Native Americans and lightning set widespread fires that burned across the landscape. Settlers suppressed these fires, allowing many plants formerly limited by wildfire to spread. When rural populations peaked, farmers grazed, burned, and cut wood from woodlands, keeping them relatively open. Now such places are pretty much abandoned, creating dense forests where only shade-tolerant plants thrive.

And our climate too is changing, with the Midwest experiencing increases in average temperatures, thus allowing more southerly plants to spread northward. Northern plants, especially those that were relicts in more southern areas, are dying out.

Soil type remains relatively constant in any given place and is based on its parent material, pH, and moisture availability. Many plants are adapted to specific soil conditions and so have restricted ranges defined by those soils. Sandy, loess, or more acidic soils based on igneous bedrock harbor many range-restricted midwestern plants.

Native plants depicted and described in this book are widely available and widely cultivated, and they will perform well in gardens across most of the Midwest. More important, they will also support the native fauna, including birds, bees, or butterfliessometimes all three. Most Northwoods, or northern relict, species are not included, as they are often very challenging to grow outside of their cool habitats.

Bur oak is a widespread and iconic midwestern tree.

The beauty of native wildflowers on the Paint Brush Prairie, Pettis County, Missouri.

Why Cultivate Native Plants?

Introduction

Introduction