Why a book for female athletes? For the last 20 years or so Ive been advising both male and female athletes on nutrition, and have realised that female athletes have different nutritional, weight and performance concerns compared with men. While men and womens basic nutritional needs may not be significantly different, female athletes often eat differently from male athletes in ways that may prevent them meeting their nutritional needs. Like women in general, female athletes are under social pressure to be thin, and this combined with the physical and psychological demands of their sport may lead to restrictive eating. Many attempt to achieve low body fat levels by unhealthy eating practices and compulsive exercise. While leanness is desirable for performance in many sports, it often comes at a price, and a large number of female athletes develop disordered eating and serious eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa.

Much research has focused on a condition known as the female athlete triad: disordered eating, amenorrhoea (the cessation of periods) and bone loss. These are often present simultaneously in female athletes who restrict their diets and undernourish their bodies due to negative body image. Disordered eating is typically the trigger of the triad. Low calorie intakes combined with intense or excessive training can cause a womans body fat level to fall so low that the ovaries can no longer produce enough oestrogen. This hormone is needed for normal menstrual function and bone formation, and low levels of it result in menstrual dysfunction (irregular or absent periods). This, combined with under-nutrition, results in a loss of bone density, and increased risk of stress fractures and osteoporosis.

Many athletes may not have the extreme symptoms of the triad, but rather may have sub-clinical stages of one or more of the conditions. For example, an athlete may show signs of restrictive eating, but not meet the clinical criteria for an eating disorder. Or she may experience menstrual disturbances, such as a change in menstrual cycle length, but not yet have developed amenorrhea. Likewise, she may be losing bone, but may not yet have dropped below her age-matched normal range for bone density.

In writing this book, I wanted to provide female athletes with the very latest information about the female athlete triad, and help them to make decisions and find support. In addition, I think that its important to recognise that female athletes come in all shapes and sizes, even within the same sport, and that very low body fat is not necessarily desirable it may have a negative impact on a female athletes health. will help you understand the consequences of achieving an optimal weight and body composition for your sport, and enable you to put into practice a healthy weight loss strategy.

If you are pregnant, or considering having a baby in the future, then you will find plenty of practical information on conception, nutrition and exercise during . It addresses the unique nutritional concerns of female athletes, and presents the consensus of medical opinion on safe exercising during pregnancy.

To help you put the nutritional advice in this book into practice, I have devised more than that are easy to prepare, and good for you too. Each provides a nutritional breakdown so you know exactly what you are eating!

I hope that you will find this book informative and helpful, and that it will inspire you to make positive changes to the way you eat and train.

Yours in health,

Anita Bean

Planning what you eat before, during and after exercise is important. A healthy diet will increase your energy and endurance, reduce fatigue and maximise your fitness gains. After exercise, you need to give your body enough of the nutrients it needs for repair and recovery.

To help you make the right food choices, this chapter explains the basis of a good training diet, what each nutrient does, how much you need and how you can achieve your ideal intake.

In your body, energy is produced from carbohydrate, fat, protein and alcohol. Carbohydrates are the bodys preferred fuel, although protein, fat and alcohol can also be converted into energy. Each nutrient provides different amounts of energy. For example, 1 g of the nutrients listed below provides the amount of energy indicated:

carbohydrate | 4 kcal (17 kJ) |

fat | 9 kcal (38 kJ) |

protein | 4 kcal (17 kJ) |

alcohol | 7 kcal (29 kJ). |

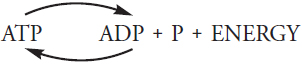

Each body cell has a small store of readily available energy in the form of a compound called adenosine triphosphate (ATP): the energy currency of your body. ATP consists of an adenosine backbone with three phosphate groups attached. When one of these phosphate groups splits off, then energy is produced (see ). Around one-quarter of this energy fuels work (such as muscular movement); the rest is given off as heat. ATP is continually being made and broken down to keep up with your bodys requirements for energy.

Normally, you have enough ATP in your muscle cells to fuel a few seconds of exercise; after this your body breaks down glucose (from your blood or from stored glycogen in your muscles) and/or fat to make more ATP and therefore more energy. You may be wondering if the source of the calories is important. If you are only considering weight loss or gain, the answer is no, it is the total intake of calories that is important. However, if you are talking about nutrition and health, it definitely does matter where your food calories come from. Generally, carbohydrates and proteins are healthier sources of calories than fats or alcohol.

Fig 1.1 The relationship between ATP and ADP

Calories are the units used to describe the amount of energy in food. In scientific terms, one calorie is defined as the amount of energy (heat) required to increase the temperature of 1 gram of water by 1C. A kilocalorie (kcal) is equal to 1000 calories.

Whats the difference between calories, kilocalories and kilojoules?

Youll see all these terms on food labels, which can be a bit confusing! One kilocalorie (kcal) is 1000 calories, and this is strictly what we mean when speaking about calories in the everyday sense. The scientifically defined calorie is a very small energy unit, which would be inconvenient to use on food labels. An average serving of any food typically provides thousands of these calories. For example, a food label would declare a portion of food contains 100 kcal rather than 100,000 calories. However, in everyday language we would probably say 100 calories.

Youll also see food energy measured in joules or kilojoules (kJ) on food labels, which is the SI (standard international) unit for energy, named after Sir Prescott Joule. One joule is the energy required to exert a force of one Newton for a distance of one metre. Again, a joule is not a large amount of energy, so kilojoules (1 kJ = 1000 J) are more often used. One kcal is equivalent to 4.2 kJ.

How can I work out how many calories I need?

Next page