My fathers purpose in life was to see the excitement of discovery from children experimenting. He was an innovator believing that students learned best by independent hands-on experiences with everyday items. Its wonderful seeing Windell Oskay bringing this book back to stimulate the next generation of children.

At first glance, projects in this book (such as building a carbon arc furnace or a hydrogen generator) may seem intimidating, even dangerous, and that is exactly the point! The science practices and skills explored through the real experiences in this publication will build the critical thinking and careful observation skills needed to support teachers and students to develop a real understanding of science. As relevant today as when it was first published, this book will support curious people of all ages to engage in serious funthe starting points for falling in love with science all over again!

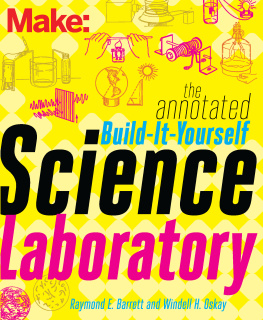

Much, much more than a DIY Lab. Its really a fairly full course in experimental science.

Forrest M. Mims III, Author and Amateur Scientist

Foreword

In this book, you will learn how to make some amazing things: a carbon arc furnace, cloud chamber, mechanical stroboscope, radiometer, optical micrometer, electromagnet, microtome, spectroscope, and so many others. You will blow glass, catch bugs, and cut the ends off of power cords. You will learn how acids and alkalis taste, what kinds of things live in a drop of water, and how your lungs draw in air. You will measure mass, density, volume, pressure, temperature, time, humidity, cosmic rays, conductivity, and optical polarization. You will isolate hydrogen, build an electric motor, grow rock candy crystals, and literally burn a record of the days weather using a CampbellStokes sunlight recorder.

While there are a lot of neat things to build, not everything is about making equipment. To look at the apparatus alone would be to miss the point; to not see the forest for the trees. At its heart, this is a science book. Every project comes with a set of questions for you to investigate, frequently challenging you, asking Can you work like a scientist? Beyond these is something yet more: one of the most extraordinary collections of science fair research project ideas ever put to paper, with over 1,600 open-ended questions for investigation, spanning the fields of chemistry, physics, biology, and geology.

All considered, this is one of the finest hands-on science project books ever written. Originally published in 1963, it has held up quite well, especially when you consider the pace of scientific and technical progress over the last half century. One reason is that it feels authentic, rather than dumbed down or bowdlerized: There are a fair number of deliciously real (i.e., potentially dangerous) projects that would never be allowed in young-adult science books today, yet were perfectly acceptable in a less litigious age. We understand many hazards better today, but as surely as night follows day, nothing in this book is any more dangerous than it was when the book was first published.

My own personal experience with this book began when I was 10 years old, in 1984, at Ainsworth Elementary School in Portland, Oregon. My fifth grade classroom made regular trips to the school library. It was at one of our regular trips that the librarian spoke to us all about the Dewey Decimal System, and how the library was organized. While I was already an avid reader, I had always simply browsed (as kids of a certain age do) among the set-out books on display whenever I visited the library. Learning about the Dewey Decimal System changed all that. The science books were in the 500s, and since I already knew that I was going to be a scientist when I grew up, the 500s were where I should be spending my time.

The science book section in a school library is apt to be inhabited by all kinds of titles, including the abstract, the esoteric, the dull, and (hopefully) the amazing. Perhaps it is little wonder that this one caught my attention, with its bold and inviting title: BUILD-IT-YOURSELF SCIENCE LABORATORY. Because, well, that was exactly what I wanted to do.

What I dont know is how many other people had this kind of experience growing up. In a sense, simply by attending school in Portland, I was (unknowingly) growing up within the authors local sphere of influence. Raymond E. Barrett was a teacher in the Portland school district for seven years before he was hired in 1959 as the education director of OMSI, the Oregon Museum of Science and Industrya post where he remained for 22 years. At OMSI, Barrett developed new hands-on, experiential approaches to teaching science. He broadened the appeal with classes, workshops, and camps. He provided leadership for science education both in the Pacific Northwest and across the nation, teaching teachers better ways to teach science.

During his years as a teacher, and later in his first few years at OMSI, Barrett began to develop a set of lesson plans for do-it-yourself science projects targeted at middle and high school students. The plans were designed to stimulate interest in the sciences, invoking Galileo, Newton, and Faraday, who (as the story goes) constructed their laboratories from the simplest possible materials. Through the plans, one could build or improvise some 200 pieces of laboratory equipment from mostly household materials, and use them in over 2,000 experiments.