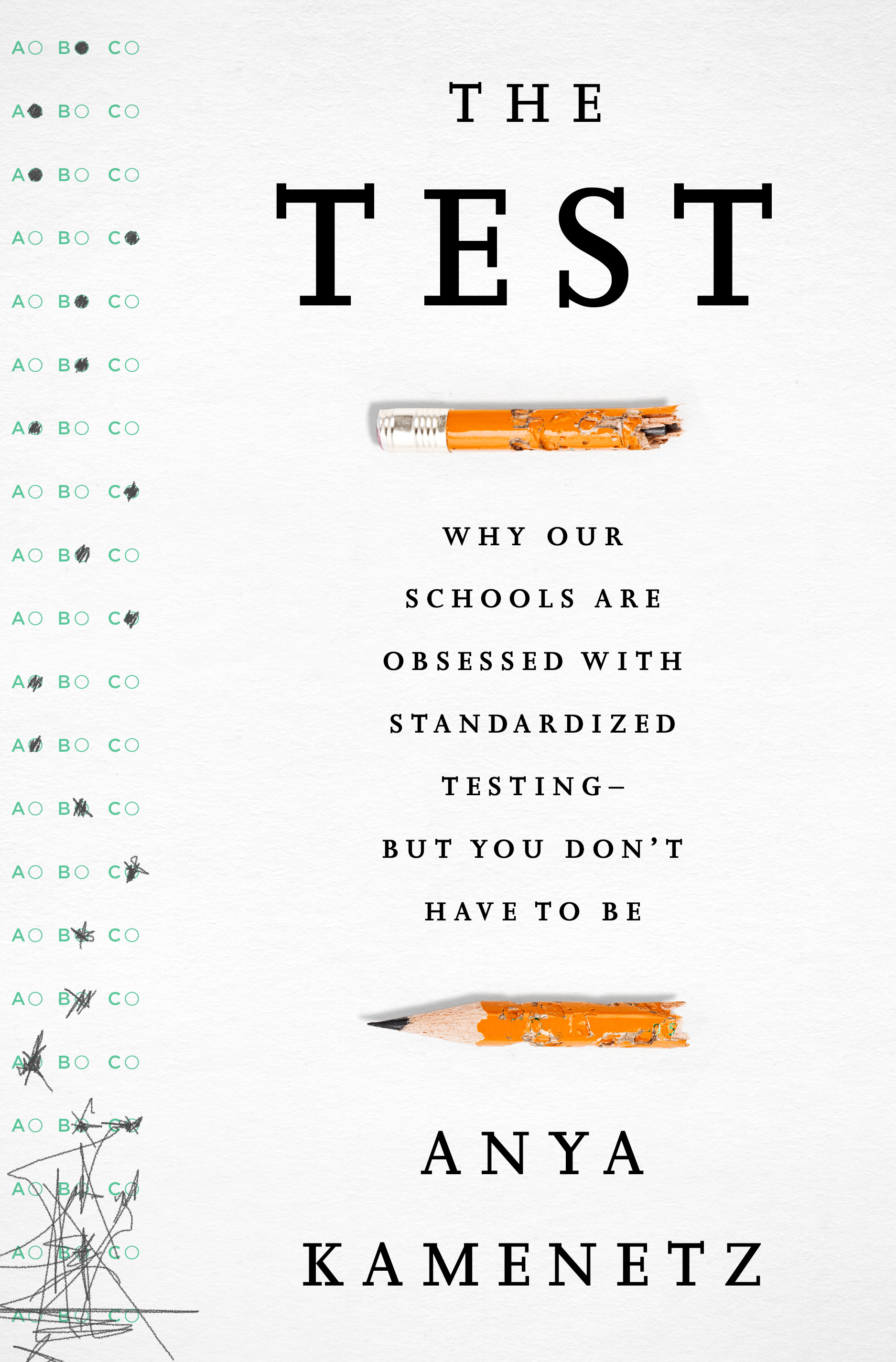

The Test

The

Test

Why Our

Schools Are

Obsessed with

Standardized

Testing

But You Dont

Have to Be

Anya Kamenetz

PublicAffairs

New York

Copyright 2015 by Anya Kamenetz.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book Design by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kamenetz, Anya, 1980

The test : why our schools are obsessed with standardized testingbut you dont have to be / Anya Kamenetz.First Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61039-442-0 (e-book)

1. EducationStandardsUnited States. 2. Educational tests and measurementsUnited States. 3. Education and stateUnited States. 4. Academic achievementUnited States. I. Title.

LB3060.83.K36 2015

371.26dc23

2014035859

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Luria Stone, who will set her own goals in life and who teaches me every day.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Part II:

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

The Problem

I m writing a book about school testing.

Thank goodness. Its about time.

Thats the conversation Ive been having again and again recently. As an education writer for the past twelve years and as a parent talking to other parents, Ive seen how high-stakes standardized tests are stunting childrens spirits, adding stress to family life, demoralizing teachers, undermining schools, paralyzing the education debate, and gutting our countrys future competitiveness.

The way much of school is organized around these tests makes little sense for young humans developmentally. Nor does it square with what the world needs.

My husband edited together a two-minute time-lapse video of our daughter learning, over several months, to walk: standing up on wobbly legs, waving her hands with a Woop! crashing back down on her rear end, toddling a few steps into our outstretched arms, and, finally, crossing a room. Its pretty irresistible, if I do say so myself.

Parenting my daughter in the first years of her life has been a master class on human development. She is so driven to explore her environment and to express herself, to communicate with, please, and sometimes resist the people around her. She doesnt just walkshe walks toward something. She doesnt just speakshe speaks to someone. Mental, physical, emotional, and social milestones are all intertwined.

In the first year or four, children are hardly ever bored, unless theyre hemmed in by Nos. They stay in the proverbial state of flow, right on the edge of their abilities. Provided they get the emotional refueling they need to feel secure, they are always reaching for the next milestone, stumbling, teetering, and getting up again.

All the experts are constantly reminding parents that infants develop on their own timetables. The overall trajectory of growth and progress is more important than any particular snapshot in time. Furthermore, early learning is as much about creative expression and social engagement as it is about parroting any memorized patterns, like letters or numbers. Good preschools are little Paris salonsfull of art, music, movement, rivalries, friendships, love, and, above all, imagination. They are also highly concerned with the practical matters of life, such as the use of forks, buttons, faucets. Folding laundry and washing dishes can be just as absorbing for toddlers as reading books and singing songs.

Yet just a few years later, when kids enter school, we start to limit our consideration of learning and development to a single hand-eye-brain circuit, forgetting the rest of the body, mind, and soul. Its math and reading skills, history and science facts that kids are tested and graded on. Emotional, social, moral, spiritual, creative, and physical development all become marginal, extracurricular, or remedial pursuits. And we suddenly expect children to start developing skills on a predetermined timetable, one that is now basically legislated on a federal level. This is what is called rigor and high expectations. But its woefully out of date.

Still, as a parent, I have to admit that if you give my daughter a testany testI want her to score off the charts. Tests seductively promise to reveal the essential, hidden nature of identity and destiny. Everyone wants to see good numbers.

This is a book about reconciling that dilemma. If you cant manage what you dont measure, as the business maxim goes, how do we measure the right things so we can manage the right things? How do we preserve space for individual exploration while also asking our children to hit a high score? Is there any way to channel the collective thirst for metrics and data into efforts that actually make our schools and our communities healthier and our children more successful?

The modern era of high-stakes standardized testing kicked into gear at the turn of the twenty-first century, with federal No Child Left Behind legislation mandating annual math and reading tests for public school children beginning in third grade. It has not been a golden age. Standardized testing has risen from troubling beginnings to become a $2 billion industry controlled by a handful of companies and backed by some of the worlds wealthiest men and women.

The near-universally despised bubble tests are now being used to decide the fates of not only individual students but also their teachers, schools, districts, and entire state education systemseven though these tests have little validity when applied this way.

Attaching high stakes to the outcomes of individual tests is an error that economists call Goodharts law and psychologists call Campbells Law. This has been stated most simply as: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

If you give people a single number to hit, they will work toward that number to the detriment of all other dimensions of success. The more you turn up the pressure to hit that number, the worse the distortion and corruption gets.

A recent example of Goodharts law is the 2008 case of thousands of pounds of Chinese infant formula and milk powder adulterated with toxic melamine. Why would you add something like this to food in the first place? Melamine is a nitrogen-based industrial compound. Dairy products are tested for their protein content to ensure good nutritional quality. But most tests of the level of protein in food actually just check for the element nitrogen, as protein is the only wholesome source of nitrogen in food. So adding melamine powder to a food raises its apparent nutritional value. The food inspectors asked for a simple numberHow much nitrogen is in this?in place of a more complicated valueIs this a healthy food? And they got what they asked for.