INTRODUCTION

To make a seed, plants do the deed. To sow a seed, dirts all you need.

Small Wonders

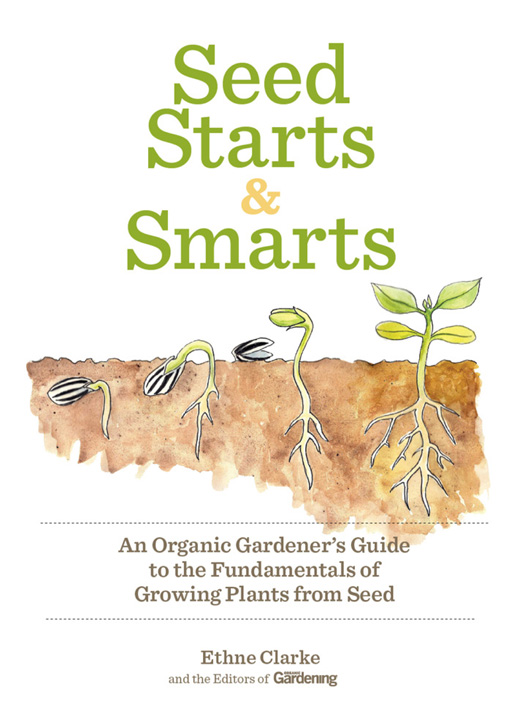

Sowing seeds is first and foremost an act of faith. Whether broadcast across the top of a prepared seedbed or tucked lovingly into a container of growing medium, seeds can seem small, inert, and inconsequential. But each one holds the promise of something much biggerjuicy tomatoes, lush foliage, brilliant blossoms. When we put a seed in contact with warm, moist soil, we see past the tiny, dry morsel to the promise it holds for a green and growing future.

Sowing seeds of plants that yield food for humans and livestock dates back to the beginnings of human history. Civilization as we know it rests on the foundation created by the earliest agricultural endeavors, when people first intentionally planted seeds and then stuck around to tend the crop and gather the resulting harvest.

Growing plants from seed can be one of the most satisfying and intriguing aspects of gardening. Almost all gardeners have grown vegetables from seed. But most kinds of plantsannuals, perennials, herbs, and even treesmay be grown from seed. Starting from seed is natures way because it worksin the wild or in the garden, seed starting is efficient, effective, and easy.

Ethne Clarke

Editor in Chief

CHAPTER 1

What Is A Seed?

Like a battery, a seed represents potential energythe promise of movement, change, and activity seemingly inert but waiting for the right conditions to activate it. Seeds come in an amazing variety of forms and sizes, from the dustlike seeds of begonias to the hefty coconut. Seeds are living links between generations of plants, carrying the vital genetic information that directs the growth and development of the next plant generation. Seeds are alive. They even breathe as we do, absorbing oxygen and giving off carbon dioxide.

From a botanical standpoint, a seed is a plant embryo with its supply of nutrients, often encased in a protective seed coat. Some of the things that gardeners think of as seeds actually are fruits, dry or fleshy, that may contain multiple seeds, but the result is the same when the right combination of warmth and moisture awakens the dormant embryos within. A few of the things that gardeners treat as seeds are not seeds at all but vegetative structures such as tubers and bulbs (see below). While vegetative structures such as onion sets may seem seedlike, they are grown in the garden more like transplants than like actual seeds.

Its not necessary to understand the botanical intricacies of how seeds are formed or to know what lies within a seeds outer coat to have a beautiful, bountiful garden. Most gardeners get along fine by just sticking seeds into soil at the right time of year, without giving much thought to pollination, dormancy, or cotyledons. But knowing what stimulates germination can inform decisions about where and when to plant each kind of seed, as well as whether to start seeds indoors or sow them directly into garden soil. Understanding how a plant is pollinated and how and when its seeds form and ripen is the foundation for preserving seeds from heirloom crops and for selecting cultivars uniquely suited to growing conditions in the garden.

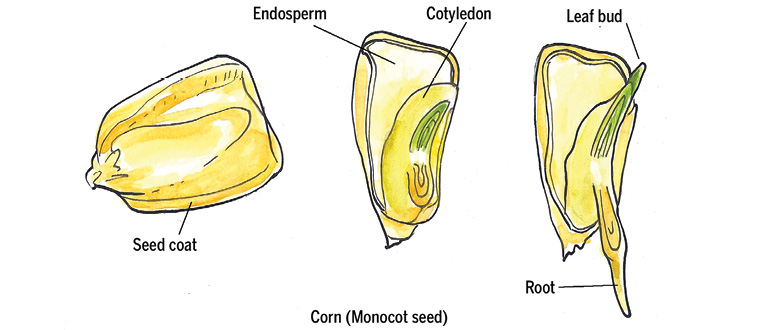

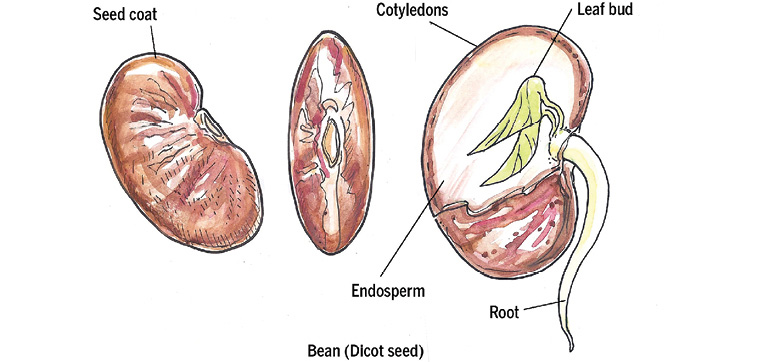

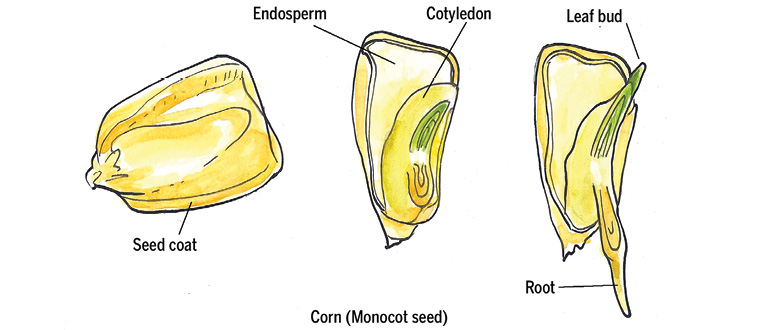

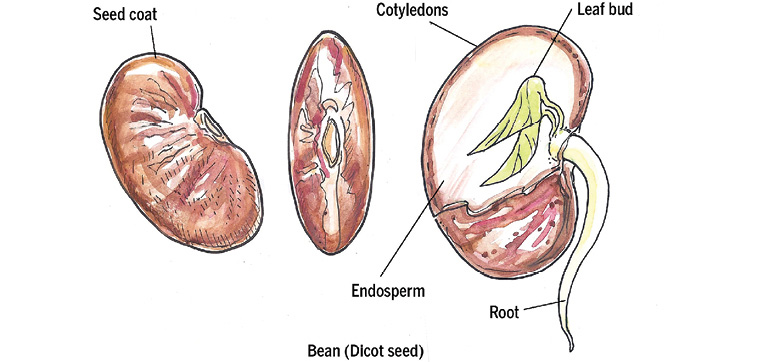

Most garden seeds contain two cotyledons, or seed leaves; these plants are referred to as dicots (short for dicotyledonous). Perhaps the best-known example of a dicot is a bean seed with its two fleshy seed leaves. Plants in the grass family, which includes all of the grains, are termed monocots (short for monocotyledonous), meaning they produce just one seed leaf upon germination. Particularly among dicots, the seed leaves often bear little resemblance to the true leaves that follow.

How Seed Is Formed

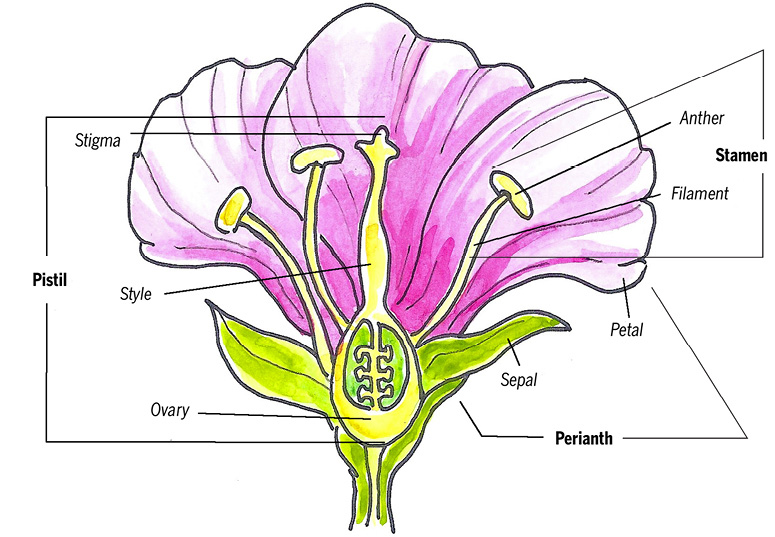

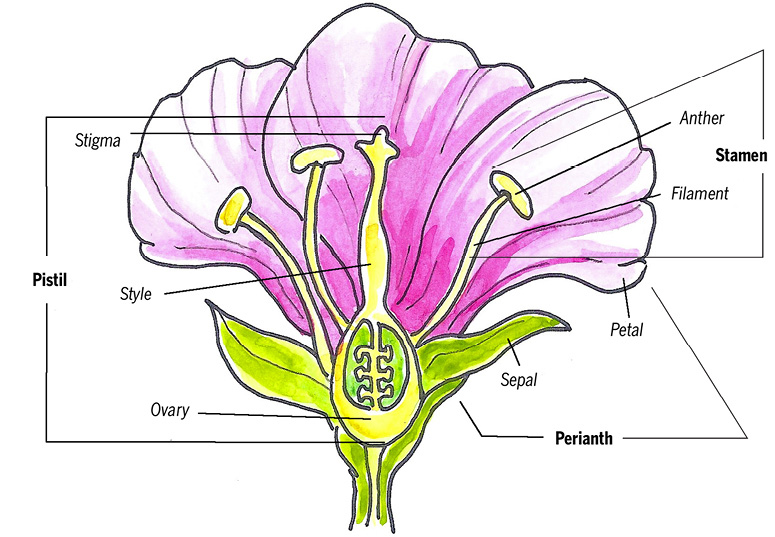

A seed is the result of plant sexual reproduction: Pollen from the male structures (collectively, the stamen) of a flower lands on the stigma, a part of the flowers female structures (known collectively as the pistil). A pollen tube grows into the style (the structure leading from stigma to ovary), and a pair of sperm cells moves through the pollen tube. One sperm cell fertilizes an ovule, creating a zygote, and the other joins with another part of the ovule to form the endosperm, tissue that surrounds and nourishes the developing embryo. The embryo sac that holds the ovule enlarges and combines with other structures to become the seed coat.

The ovary, which may contain a few or a few dozen or even hundreds of ovules, becomes the pod or fruit that holds the seeds as they mature and ripen to the point at which they are capable of germinating and growing into plants that carry the genetic characteristics of their parent plant(s). Among the thousands of species of flowering plants, this process is both remarkably similar and amazingly diverse. Seed formation happens pretty much as described here, regardless of whether the resulting seed is that of a bean or a sunflower or an oak. But the forms of the flowers involved in the reproductive process, the methods by which pollen is transferred, and the resulting qualities of those seeds and their associated structures (fruits, pods, ears, and more) vary widely betweenand even withinfamilies of plants.

Botanists use the number and arrangement of floral reproductive structures to classify plants into families and further divide them into genera and species. Gardeners who want to dabble in plant propagation should learn about the reproductive structures and methods of plants for more practical reasonsto know how to encourage production of edible plant parts and ensure the production of seed for future crops.

A perfect flower is one that has both male and female reproductive structures. Beans, peas, and tomatoes are among the popular garden crops that have perfect flowers. Flowers may be further described as complete or incomplete, based on whether or not they also have both petals and sepals (collectively, the perianth).

Vive la Diffrence!

Most garden crops have perfect flowersthose with both male and female reproductive structures. However, imperfect flowersthose with either male (staminate) or female (pistillate) reproductive structures but not bothmay be seen in the garden, too. The most common examples of imperfect flowers bloom on the vines of plants in the cucurbit familycucumbers, squash, melons, pumpkins, and gourds. These plants are described as monoecious, meaning that both male and female flowers are borne on the same plant. The male flowers make pollen that is carried by insects (or savvy gardeners) to the female flowers; for the most part, only fertilized female flowers produce fruits.