William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2018

Copyright Richard Jones, 2018

Richard Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

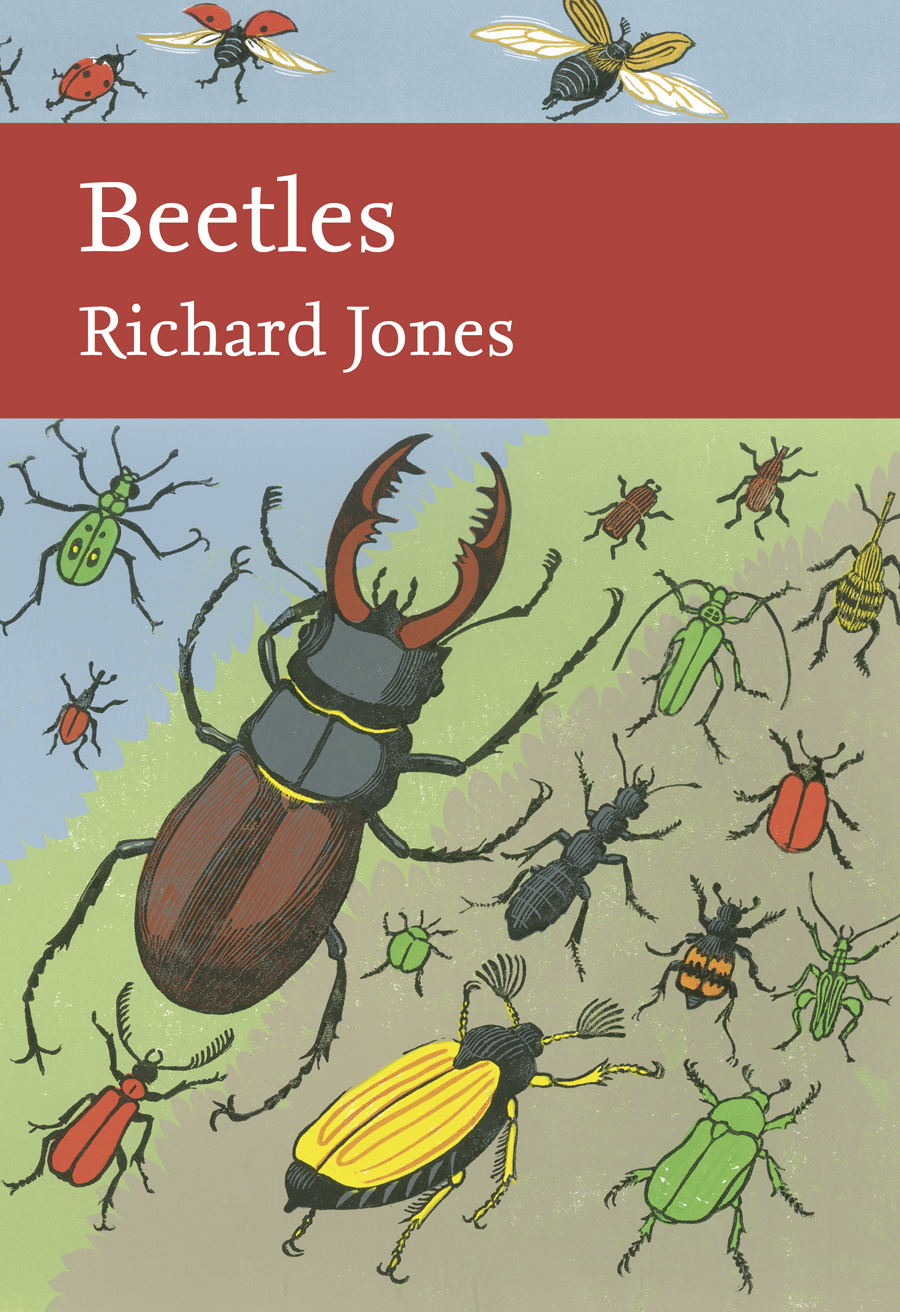

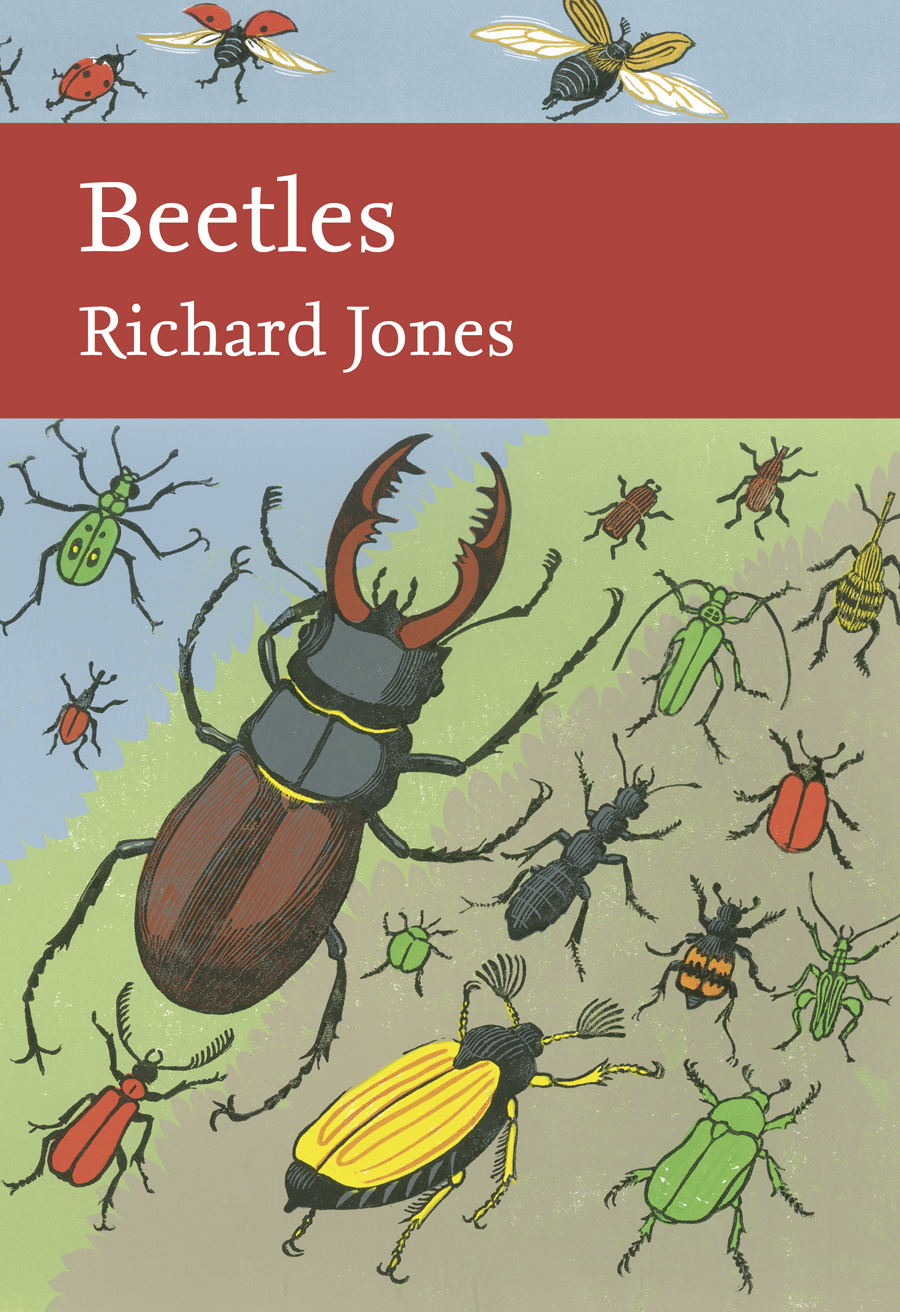

Cover design linocut by Robert Gillmor.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008149529

Ebook Edition January 2018 ISBN: 9780008149512

Version: 2018-01-17

to Peter Hodge, coleopterist, mentor, friend

Contents

EDITORS

SARAH A. CORBET, S C D

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIB IOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIH ORT

P ROF . JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

P ROF . BRIAN SHORT

*

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

W HY HAS THE NEW NATURALIST LIBRARY waited so long to produce a book on beetles? We have long known that we needed one beetles are ubiquitous, intriguing and much loved by many, from Charles Darwin to Christopher Robin, but they are surprisingly poorly covered in the literature. Comprehensive accounts of their natural history have been few, and until recently the keys needed by beginners to gain access to the group have been out of print, out of date or generally out of reach in terms of price. We knew that writing this book would be a challenge, requiring a huge fund of knowledge, boundless enthusiasm and an ability to do justice to a complex subject without flooding the reader with detail. It took time to find the right author. We are very glad that Richard Jones consented to meet the challenge, and we are delighted with the result. This book illustrates the pleasure that can be derived from the study of beetles, giving a conspectus of the group as a whole and delving into the quirks of natural history that make them so fascinating, and we expect that the key to beetle families and the listing of literature that enables one to move on to a species identification will help to remove some of the barriers that prevent more naturalists from indulging in coleopterology. Many established British naturalists found their early inspiration in a New Naturalist volume, and we expect this to inspire a new generation of beetle enthusiasts.

B EETLES ARE, ARGUABLY , the most important organisms on Earth. With nigh on half a million beetle species already described and catalogued in the worlds museums, there are more types of beetle on this planet than any other group of creatures (quietly brushing aside nematodes for a moment, perhaps). They are certainly more diverse than any other category of living thing. Even so, we still know so little about them. Of those we do know, and have given names to, we hardly have a clue about their life histories, their larvae, their predators, or their interactions with other plants and animals. There are an estimated 13 million more beetle species out there waiting to be discovered, mostly in the deep, dark, dank rainforests of the tropics, although some would argue 30 million species are likely to exist. Even the experts cant agree.

This astonishing species diversity is matched by a similar diversity in shape, form, size, life history, ecology, physiology and behaviour. In effect, beetles occur everywhere, and do everything. And yet beetles form a clearly discrete insect group, typically characterised by their attractively compact form, with flight wings folded neatly under smooth, hard wing-cases. Almost anyone could recognise a beetle; indeed, many are intimately associated with human society. Groups like ladybirds are familiar to us from a very young age. Large stag beetles and handsome chafers are celebrated for their imposing size or bright colours. The sacred scarabs of the ancient Egyptians were given iconic, if not god-like, status, and even though the exact religious meanings may be fading after three millennia, the beetles images remain in bewitching jewellery and monumental statuary.

Despite our ancient and easy familiarity with beetles, the order Coleoptera remains tainted by the notion that it is a difficult group of insects to study. The traditional routes into studying British natural history, through birdwatching, butterfly collecting (back in the day) and pressing wildflowers, now extend to studying dragonflies, bumblebees, grasshoppers, moths, hoverflies and even shieldbugs. These are on the verge of becoming popular mainstream groups, but beetles remain the preserve of the expert, or so it seems. This is a shame, and something Id like to set right with this book. Many British beetles are easy to find and easy to identify by the non-expert, but that bewildering background diversity, and the daunting numbers of species in the Coleoptera as a whole, have been enough to dissuade many a potential coleopterist from grasping the nettle and getting stuck in.

We are very lucky in Britain, in that we have a long and noble history of studying wildlife, call it what you will, from natural philosophy to nature conservation to citizen science. Insects, by virtue of being small and easily caught and examined, have led the way beetles especially. It is no coincidence that Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace were, first and foremost, entomologists. Actually, no, any reading of their lives and works shows that they were, self-evidently, not just entomologists; they were coleopterists.

At school, at university and in my early professional life in medical publishing, my interest in insects was seen as a bit weird. But once any initial amusement at my curious demeanour had passed, I slightly relished the fact that I was the holder of a secret arcane knowledge, from which my contemporaries were self-excluded. That stag beetles grew from maggots, and not from smaller beetles, was a revelation to otherwise intelligent and well-adjusted friends. Visiting relatives in Florida 25 years ago, I found four species of beetle infesting a Tupperware box of flour in their larder; they were horrified, and not overly happy with my forensic dissection of the many hundreds of specimens in the congealed mess. I do, however, like to think that they were enlightened by my enthusiastic discussion of the beetles, and the fact that they represented four different beetle families, and had four different evolutionary routes, from bird nests, hollow trees, bumblebee colonies and leaf litter, into the twentieth-century cornucopia of the North American kitchen habitat. And, of course, every time a child asks Are ladybirds poisonous?, I can answer with a certainty that I know will startle them: Yes they are, but you have to eat quite a lot of them to do any real harm. These simple basics of biology, ecology, physiology and evolution are a mysterious closed book to most people.