VOLKSWAGEN BEETLE

Richard A. Copping

For 1958, when a much larger rear window was introduced, Reuters turned his car around to display this asset to best advantage.

The Beetles success story was essentially one of availability across the world.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

H AILED AS AN icon of the twentieth century, the Beetle luxuriates in the unchallengeable position of being the most produced model of a single type ever, with 21,529,464 examples having been built in a continuous run spanning the years 1945 to 2003. Instantly recognisable as the same car, whether of 1949 vintage and the arrival of the first De Luxe version for export, or the last German-built example dating from January 1978, or indeed the ltima Edicin manufactured in Puebla, Mexico, in 2003, a Beetle is a Beetle. Other car makers may choose to overlook this fact, preferring to promote their own models as the most produced, but, without exception, such pretenders to the crown carry little more than continuity of name.

On 17 February 1972 Beetle production numbers exceeded those of the Model T Ford. Its origins are decidedly murky, but clearly there would have been no Volkswagen without Hitler and the Nazis, despite the protestations of supporters of its designer, Ferdinand Porsche. Similarly, if the Nazi-built and owned Beetle factory had not been located in the British zone of occupation, the buildings would probably have been demolished and the assets distributed as war reparations. Equally, there would not have been an army officer present with the ingenuity to produce a vehicle as much needed transport for occupying personnel. That the Volkswagen saloon and not its military sibling, the Kbelwagen, was the only option remains a further quirk of fate.

Above all, if a former director of Opel had not been appointed Director General of the Volkswagenwerk in January 1948 and taken the highly unusual step of developing one model to perfection, rather than replacing it every few years, Volkswagen might well have survived, but its first car would have become obsolete by the mid-1950s. Heinz Nordhoff held faith with the Beetle until his death in April 1968. He had made it his lifes aim to achieve where Hitler had failed, although his terminology would have differed somewhat. Under his tutelage, the Beetle successfully won over Europe, including fiercely independent Britain, conquered the United States, extended its influence into Australasia, and became a mainstay of the Brazilian and Mexican economies.

Technical details are kept to a minimum in this book: they are not the kingpins of the Beetles story. A basic specification of an early model is all that is required:

Length: 4,050 mm. Width: 1,540 mm. Height: 1,500 mm. Wheelbase: 2,400 mm. Track: front, 1,290 mm; rear, 1,250 mm. Total weight: 1,100 kg.

Construction: frame with tunnel-shaped centre section forked at the rear, welded-on platforms. Front axle: independent suspension through longitudinal upper and lower torsion bars, two square sets of torsion bar leaf-springs passing through beams. Rear axle: independent suspension through swinging half axles with spring plates, one solid round torsion bar spring on each side.

Engine: four-cylinder, four-stroke rear engine with horizontally opposed cylinders, air-cooled. Bore: 75 mm. Stroke: 64 mm. Capacity: 1,131cc. Compression ratio: 5.8:1. Maximum PS (Pferderstrken [Metric horsepower]): 25 at 3,300 rpm.

Throughout the 1950s Volkswagen could not meet the demand for the Beetle. By the mid-1960s, when this picture was taken, 4,550 Beetles were being manufactured daily.

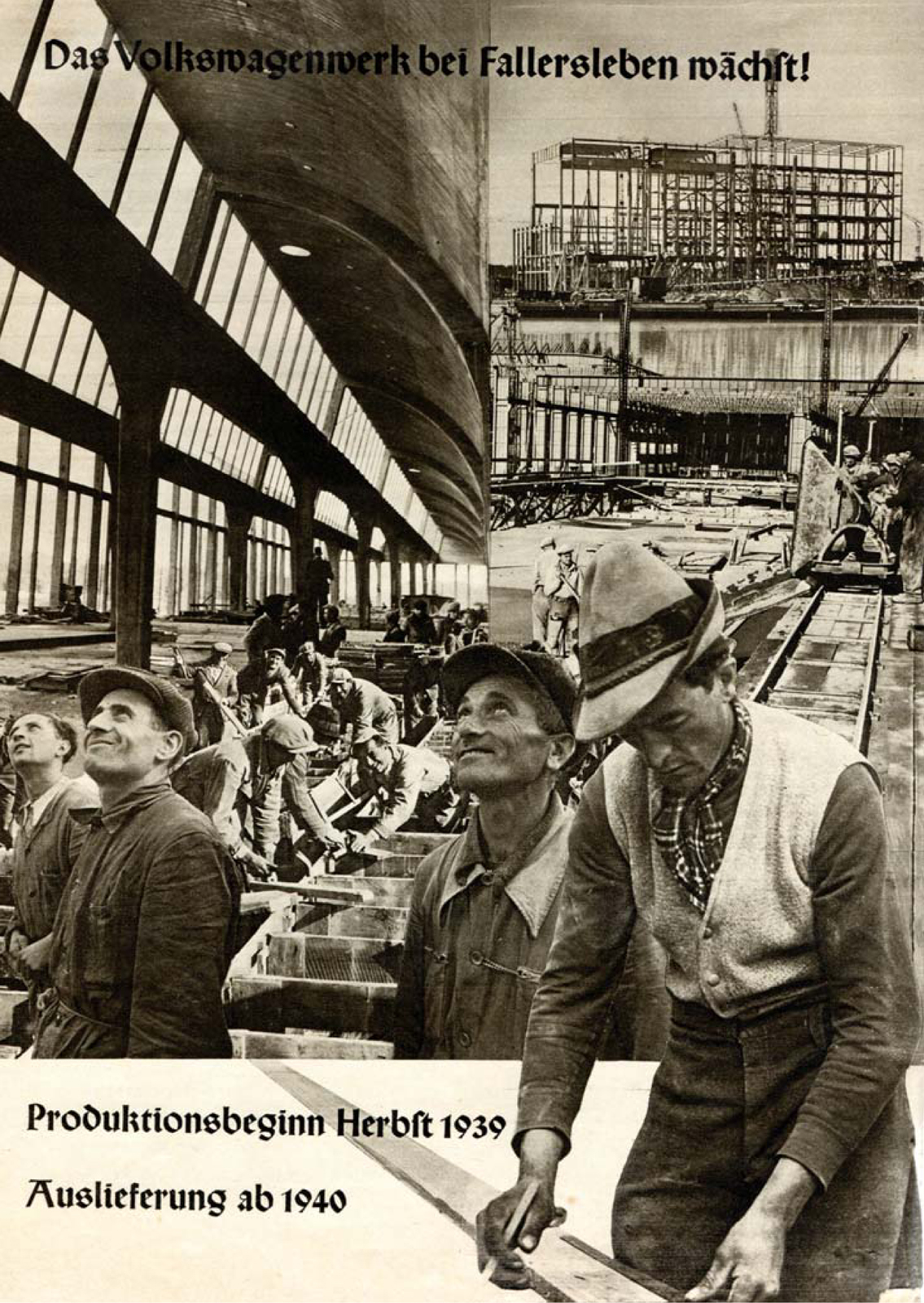

Nazi propaganda depicted starry-eyed construction workers gazing admiringly upwards at the wondrous factory they were building.

A CAR FOR THE MASSES: 193345

O NLY DAYS AFTER his appointment as Germanys Chancellor, a smartly suited Adolf Hitler addressed journalists and car manufacturers as he opened the 1933 Berlin Motor Show. His theme was the need for the rapid motorisation of Germany to be effected by tax incentives for car buyers, the repeal of legislation demanding would-be drivers pass a test, the promotion of motor sport and, most significant of all, a vast programme for the construction of autobahns.

Germany lagged far behind other European countries in terms of car ownership. As recently as 1927, statisticians were citing a figure of one car for every 196 citizens in the Weimar Republic, compared to one for every forty-four people in both France and Great Britain, and the very impressive ratio of one automobile per 5.3 United States citizens. The Depression of 1929 and beyond only aggravated the situation. The lack of modern American-style assembly lines and a reliance on labour-intensive production methods both stunted growth and ensured high prices. Similarly, high material costs, a result of Germany being deprived of over 30 per cent of its coal reserves and 75 per cent of its iron-ore mines in the redistribution of territory following the First World War, drove prices out of the reach of the average citizen.

Hitler recognised that many of those most attracted to his cause earned from as little as 160 Reichsmarks per month up to a maximum of 500, while supporters with savings were likely to have seen them dwindle to less than 1,000 Reichsmarks by the time he took office. Opels cheapest car cost 1,800 Reichsmarks, and even attempts at producing models with two-plus-two seating, and with little more than an outboard motor to power them, were likely to be offered at 1,500 Reichsmarks.

Ferdinand Porsche, renowned for his powerful racing cars and luxury models, as well as his fiery temperament, had tried in vain for thirty years and more to bring a small car to the market, a vehicle for the masses rather than for the upper classes. After years of bitter disputes with a string of employers, Porsche set up his own design studio on 1 January 1931. Not long afterwards, Fritz Neumeyer, owner of the Zndapp motorcycle company, offered him a commission. However, by 1932 the project, featuring a car with a passing resemblance to a Beetle, fell by the wayside as Neumeyer came to realise just how costly the essential stamping presses would be. The following year, to Porsches delight, NSU offered a similar commission, but again he was deprived of his goal. Apart from concerns on the part of NSU about the investment required and the available capacity to build such a car, a forgotten agreement between the company and Fiat came to light, the crux of which was that NSU had agreed never to build a four-wheeled car under its own name.

Hitler and other high-ranking Nazi officials admire Ferdinand Porsches small car, seen here in Cabriolet guise.