Foreword

by Phil Plait

(aka the Bad Astronomer)

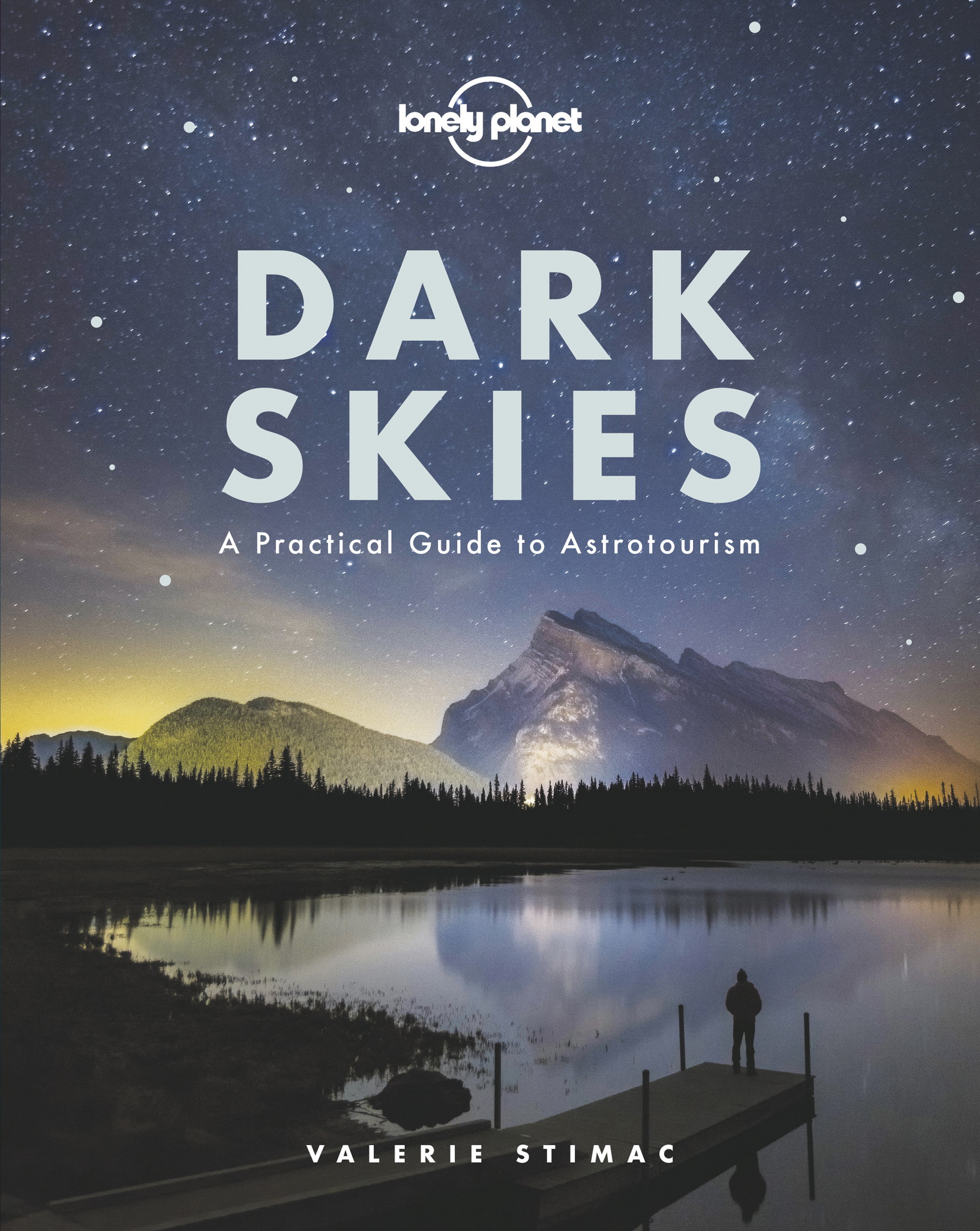

W e had been driving for hours, my wife and I, and were exhausted when we finally arrived at the dude ranch in western Colorado. The drive through the mountains had been gorgeous but extended, and the sun was going down when we finally pulled in.

We ate dinner by twilight, and before we could even really unpack our bags, the light in the sky was gone and the view out our cabin window was utterly black. I suggested sleep, but Marcella had different plans. I want to see how the sky looks, she suggested, and how could I resist? I found our coats and red-covered flashlights, and we faced the brisk (and thin) air to start walking along the creek that flowed behind the cabin.

We picked our way along a trail, sleepiness and unfamiliarity slowing our progress. Rural Colorado has plenty of wildlife, and I kept a wary eye ahead or to the sides, peering into the darkness of the trees around us to make sure we were the only ones enjoying the outdoors.

After a few hundred yards the trail opened up into a clearing. I was still wearily scanning around us for critters when I heard my wife gasp. I turned and saw that she had turned off her flashlight and was staring up, mouth open, gawking. Clicking my flashlight off as well, I followed her gaze upward, already knowing what Id see. And I was right.

Thousands of stars shone down on us. The Milky Way, usually a barely hinted-at phantom from our home, was like a solid structure arcing over our heads. So many faint stars were visible that it took me a moment to get my bearings, even though Ive been an astronomer my whole life and have spent thousands of hours under the night sky.

Gianni Triggiani / 500 px

Myriad thoughts jammed into my head, expressions of awe and wonder and beauty. But Marcella was able to synthesise all of them into a single breathy, exhaled sigh. Oh my God, she muttered. I smiled, agreeing. Oh, how I missed this view!

The thing is, Im lucky. I knew what I was missing.

In 2016 a study published in Science Advances mapped the glow of the sky caused by artificial lights and compared it to population location. The result was jolting: about 80% of the worlds population lives under light-polluted skies. In the US that number jumps to 99%. Hundreds of millions of people in the US cannot go outside, look up and see more than a handful of stars. We have erased the treasures of the universe from our lives, that light that had travelled for centuries, millennia, to reach our eyes.

Of course illumination at night is important. We humans arent all that good at being tied to the sun; our civilisations activity has spilled over into the night, and we need to see what were doing. This in itself isnt the issue; the problem is light thats wasted, shining up instead of down, thrown into the sky, illuminating the air around us and washing out the stars. Millions of people grow up under a sky that, at night, is as lifeless and dull as a pothole filled with brackish water.

Not to be too flatly obvious about it, but the entire universe is up there, and were missing it. Even in our own atmosphere, there are wonders to see. Shooting stars, meteors created from tiny bits of interplanetary flotsam shed from passing comets, burning up 50 miles (80km) above our heads as they ram through the air at hypersonic speeds. Aurora flowing and glimmering, caused by the wind from the sun interacting with molecules in the air even higher up, creating cascades of electrons jumping around their atomic hosts, emitting individual photons of light in numbers too high to count.

Continuing on past our atmosphere, there are satellites to watch as they orbit in near-earth space; the planets as they circle the sun; stars and clusters and nebulae; and galaxies that are so numerous that a grain of sand held at arms length blocks out tens of thousands of them.

This is what were missing. But theres some good news in all this: it doesnt have to be this way.

Dark-sky advocates are gaining traction, able to convince authorities that we dont necessarily need fewer lights, we need smarter ones lamps that illuminate the ground and not the heavens. Designated dark-sky sites are growing in number and popularity, and more people are becoming aware of astrotourism and heading out into less-populated areas to see the skies.

Even better, you need not go too far to sky gaze. Sometimes the nearest window will suffice. You can see lunar eclipses from anywhere, as the shadow of the Earth slowly covers the moon, and solar eclipses are of necessity observable during the day. The planets are visible even from the downtowns of major cities, and the moon is always a joy to see even with modest optical equipment.

Still, theres so much more to see, and places to go to see it. And heres the best part yet: in the pages of this book you have a guide in Valerie Stimac. She shows you how to find your way out and up to the best places to experience all the different wonders the sky has in wait for you. Heed her advice, and the whole of the cosmos is open to you.

Standing in that clearing in the remote Colorado Rockies with my wife that night, the two of us slack-jawed and silent, soaking in the constellations, a familiar thought crossed my mind. I have always been amused at the expression we use when we want to leave our crowded, overlit cities and suburbs and head out to some remote, quiet, dark location: getting away from it all.

Thats exactly backward. When you travel away from those lights, you leave behind nothing: a blank sky. When you travel to these dark sites, you fill that blankness with the entire universe above you. Youre not getting away from it all. Youre heading towards it.

Danita Delimont Creative / Alamy Stock Photo

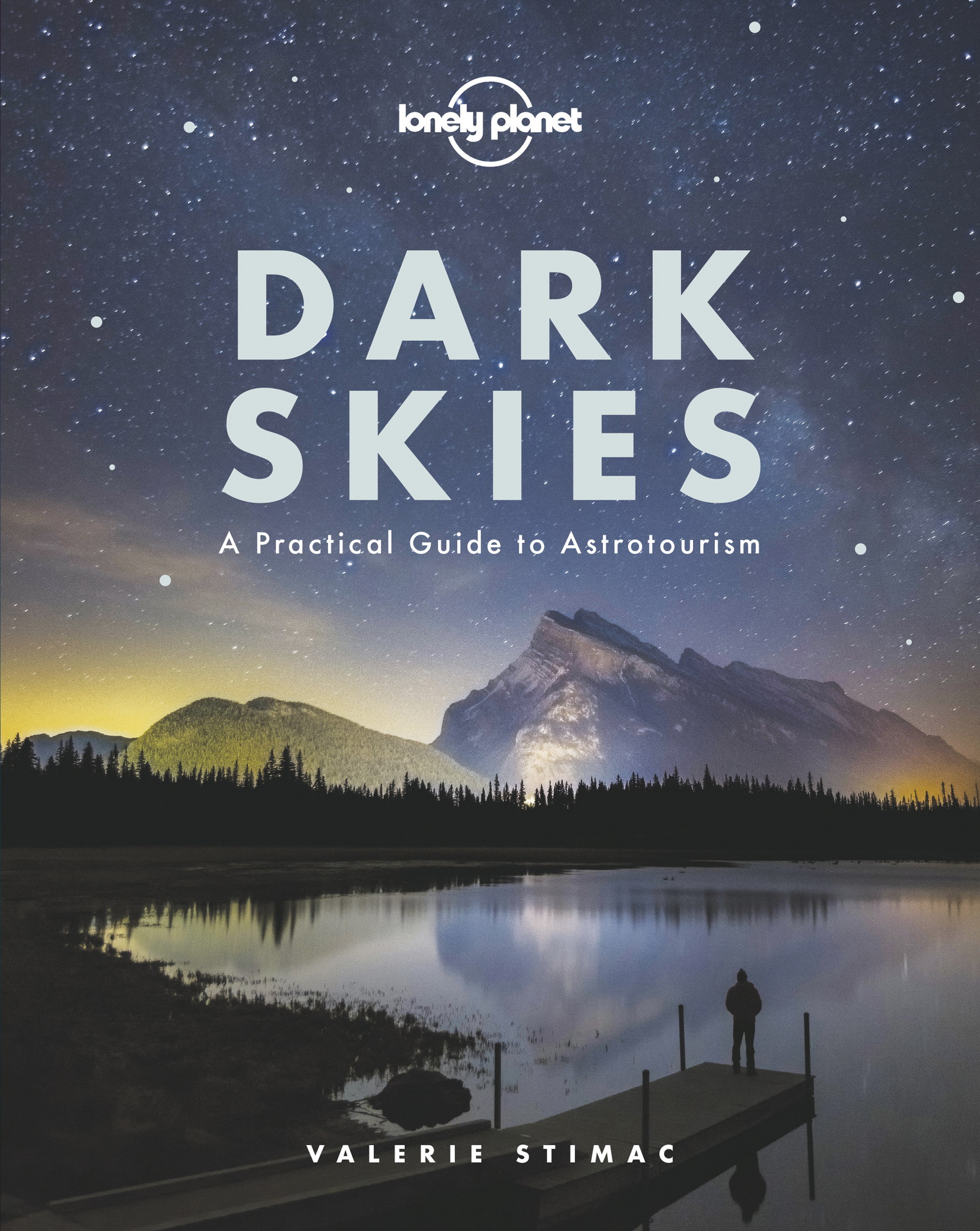

Introduction

by Valerie Stimac

W hen the cloudy expanse of the Milky Way stretches above us from horizon to horizon, or a meteor streaks across the sky, or a rocket defies gravity to leave Earth, it touches on a sense of wonder and awe. There is something breathtaking and humbling about the knowledge that beyond the protective layer of our atmosphere, there is a lot more out there. The universe is vast almost beyond comprehension: while technology helps increase our knowledge of moons, planets, and suns, we can hardly imagine how many other places there are in our solar system, galaxy, and the universe once you leave planet Earth.

The natural world on Earth never ceases to amaze us; we make pilgrimages to Everest, Niagara, the Amazon, and countless other awe-inspiring sites on our bucket list. But somehow, the night sky is often omitted from the list of natural experiences we should seek out. Yet its magnificence can be even more overwhelming than terrestrial wonders. For millions of years, the stars have wheeled overhead, and the planets have performed their celestial dance. Observing this pageant used to be a nightly ritual for humans across the planet until very recently. But while we often book trips to explore new cities and try new foods, we rarely do the same for astronomical phenomena and space experiences. We may have gone stargazing as a kid or learned about astronomy in school, but we dont journey to discover it firsthand. In not seeking out encounters with astronomical phenomena, whether at the certified dark sky parks listed in this book or by viewing a meteor shower or eclipse, we deprive ourselves of a magical experience. Less than one hundred years ago, seeing the unobscured night sky was a birthright; now it is inaccessible to urban and suburban residents across the globe. Yet its still in reach if we seek it out.

Next page