1 Sizing Up the Case

This book is not going to be another oration on bridge technique. Terms such as safety plays, squeezes, endplays, and coups will have little or no place here, and any references to them will be in name only. What will be discussed are the thought processes of the good player as he is proceeding through a hand that requires one correct guess for success, or perhaps a series of correct guesses.

If you have ever watched the play of someone who has a firm understanding of the ideas presented in this book, at the end of a hand you may have asked such questions as:

What made you play East instead of West for the queen of spades?

How did you know the king of hearts was singleton?

Why did you finesse the diamonds instead of the clubs?

The answers to these questions come from applying the rules of card placing or card locating, and this book intends to give you guidelines for determining who has which cards. When you know where the cards are, it will be much easier to apply the aforementioned bridge techniques.

This chapter will take a brief look at some hands, and will discuss them from two points of view:

(1) No information is available, i.e., no bidding and a noninformative lead.

(2) There has been a helpful auction, or the opening lead gives some information.

Frequently throughout this book questions will be asked. Attempt to answer them before going on. Learning is always a process of observing and doing. The questions will be real-life situations, and you should take the time to answer them, for they will approximate actual conditions at the bridge table.

Always note the information given. Try to make this a habit, so that it is not necessary to refer back. Look at the auction when given, note the opening lead, who has shown up with what card or cards, etc.

Opening leads in this book are standard. The defenders will lead the king from sequences headed by the ace-king or the king-queen. The ace is led from the ace-king doubleton, or when leading partners suit. The queen is led from sequences headed by the queen-jack, or it may be a doubleton or a singleton. In real life, as in this book, most of your opponents will use standard leads, for it is more important for the defenders to try to give each other information early in the play than to try to deceive the declarer.

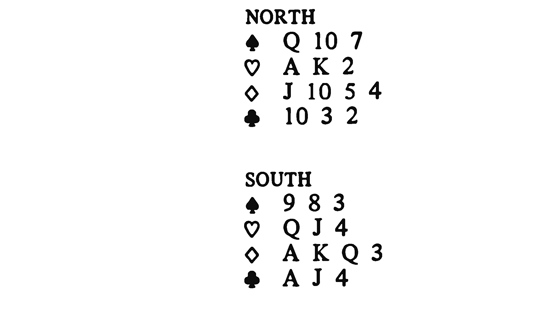

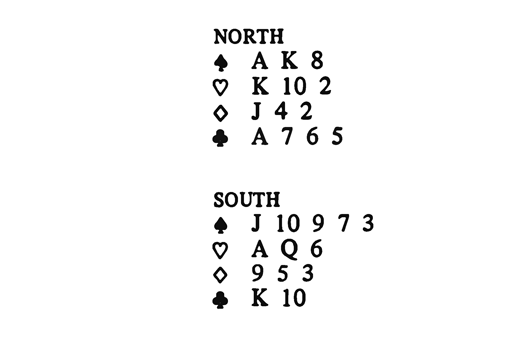

You are in three notrump:

How would you play three notrump in these three cases?

(1) East-West did not bid, and West leads a heart.

(2) East-West did not bid, and West leads and wins the spade king and then shifts to a heart.

(3) West opened the bidding with one club and then leads a heart.

Answers:

(1) With no clues to go on, your best play for your ninth trick would be to lead the spade nine and finesse against Wests hoped-for jack.

(2) Wests lead of the spade king tells you that he holds the spade ace as well. This time you should lead a spade to the queen.

(3) Your side has 27 points in high cards. The opponents have 13. If West truly has an opening bid he will have the ace and king of spades. Unless you feel he is fooling around with his opening bid, you should lead toward the spade queen. It would be wrong to play to the spade ten, as it is just barely possible that East holds the jack.

In these examples you were simply given different information which gave you reasons to approach the play of the same hand in different ways. It is almost as though you had to solve three different problems, even though at first sight they seemed to be the same.

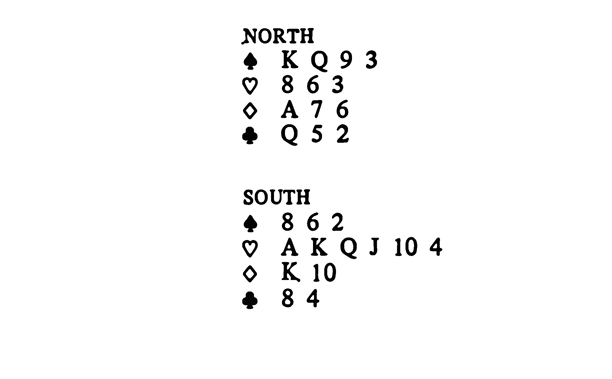

A look at a few more hands may help to give you a feel for this approach. This time you are in four hearts.

How would you play this hand under these varying conditions?

(1) No opposing bidding. West leads the trump nine.

(2) East opens one club. West leads the ace of clubs and continues with the three of clubs. You trump the third club, with West following suit.

(3) No opposing bidding. West leads the spade jack. Dummys king wins the first trick.

Answers:

(1) With no clues, you should just lead spades toward the dummy twice. Hope West has the ace of spades.

(2) If, after Easts opening bid, you believe he has the ace of spades, then you should finesse the nine on the first round of spades. If you play the king or queen, East will win and you will have a sure spade loser remaining.

(3) Wests lead of the jack seems to imply possession of the ten while denying the ace. Easts refusal to play the ace does not deny his having it, and your best play is to finesse the nine of spades on the second round of the suit, hoping West has led from the jack-ten sequence.

Here again you played differently as a result of information gainedonce from the auction and once from the opening lead.

You are again in four hearts. (partner forgot to leave you in three notrump).

How do you play if:

(1) No opposing bidding. West leads the club queen.

(2) No opposing bidding. West leads the spade queen.

(3) East opens one club. West leads the club ten.

Answers:

(1) Unless you get some strong feeling (like someone shows you his hand), you should lead a spade to the king. This wins if West has the spade ace.

(2) The opening lead indicates that East has the spade ace, so nothing can be gained by covering. But if East has only two or three spades, you can get a spade trick by playing low twice and if necessary, trumping a third round in your hand. Hopefully the ace will drop. Now the spade king can be used to discard the club or diamond loser.

(3) This time the opening bid has told you where the ace of spades is. Unless East has psyched an opening bid he has that card, and playing to the spade king will be a foregone failure. It is correct to playas in example 2 and hope that the ace of spades falls on an early round.

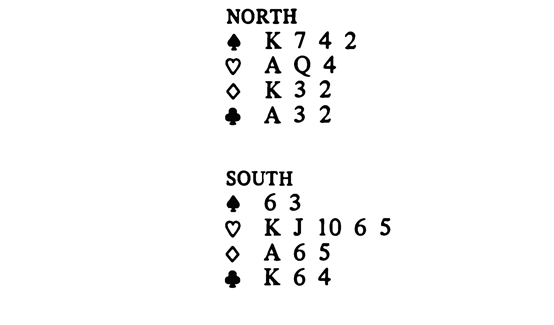

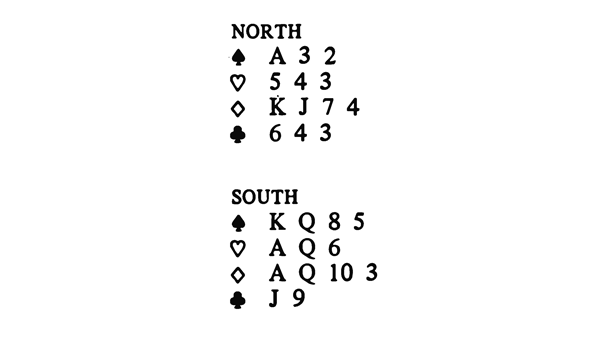

Another game hand, this time four spades.

How do you proceed in the given circumstances?

(1) No opposing bidding. West leads the club queen.

(2) No East-West bidding. West leads the spade six.

(3) East opened one club. West leads the club queen.

Answers:

(1) With no particular clues you should play the ace of spades to see if the queen drops. If it does not, finesse in spades and hope West has the spade queen with a maximum of three spades in his hand.

(2) Wests lead of a spade would be very unusual if he has the queen. Here it would be right to play the ace and king of trumps and hope East has the queen either singleton or doubleton.

(3) East-West have only 15 points in high cards. West has led the club queen, meaning East has a maximum of 13. If West has the spade queen, then East has opened on a hand containing no more than 11 points. Unless East is a notoriously light opening bidder you should play the ace and king of trumps, hoping to drop the queen.

In this last hand you are in three notrump.

What considerations do you give to the following set of situations?