Grow the Best Strawberries

Louise Riotte

Louise Riotte

CONTENTS

Introduction

Do you remember the strawberries of your childhood, dew-covered and fresh-picked on a bright June morning? They had a delicious aroma and melt-in-your-mouth sweetness totally unlike any store-bought berries you ever tasted. And how good they were in a warm shortcake topped with a light mound of real, fresh-whipped cream. Can you recapture all this glory? You bet you can.

If there is one fruit every homesteader and suburbanite should grow, it is strawberries, for strawberries are:

The first fruit of the season.

The quickest to bear of any fruit.

Easy to grow.

Expensive in stores.

Better quality when home grown.

And no matter where you live, there is a variety that will thrive and do well in your region. Though they do best in the cooler, moist regions, they can be grown in hot, dry climates, especially where windbreaks can be provided and supplemental watering is possible during the critical months of July, August, and September.

Strawberry plants respond for the gardener in direct proportion to the care they receive. Larger yields of high-quality fruit await those who improve the soil, devote extra attention to cultivation, provide irrigation if needed, and mulch the planting properly.

Strawberries (Fragaria chiloensis in the family Rosaceae) are the first fruit to ripen in the spring, and they are highly nutritious. A single portion of fresh strawberries supplies more than the minimum daily requirement of vitamin C. There is, in fact, more vitamin C in a cupful of strawberries than in a medium-sized orange or half a medium grapefruit. Fresh, high-flavored, undamaged fruit generally contains more vitamin C. Preserving or freezing may destroy a sixth to a half of the vitamin C content.

How They Grow

Set healthy plants in moist soil in your prepared bed in early spring. They will produce new roots in a few days. A few days later, each plant usually has several new leaves of normal size.

For those plants that send out runners (most of the popular varieties do), runners will begin to emerge in June. Growing from where the leaves join the main stem, these runners will form new plants, which will take root near the original plant. New runners then grow from the new plants, and in this way a succession of independent new plants soon is growing around the original plant.

Plants produce blossoms the first year, and these will develop into fruit if they are not pinched off. Do pinch them off, which will encourage your plants to develop strong root systems and vigorous growth. Your reward will be next seasons abundant crop of large, healthy, delicious berries.

In the fall, the growing points in the crown change into blossom buds. The buds grow rapidly, and by the end of October they can readily be seen by opening the crowns. In vigorous plants, buds also develop in many of the leaf axils. The number of leaves on a plant in the fall is a good indication of the following years production: The more leaves, the more berries the plant will produce the next spring.

Plants become dormant in the fall, and the older green leaves and connecting runners die.

In the spring of the fruiting year, the buds that developed last fall develop into blossoms. The first one to open on a cluster contains the most pistils (female elements), is the largest, and becomes the largest fruit with the most seeds. The next one to open becomes the next largest fruit, and later ones become successively smaller fruits.

Strawberries in mild weather mature about 30 days after blooming. In warm weather they will mature more rapidly.

Selecting Your Best-Bet Berries

There are three distinct fruiting habits in strawberries. The first, and most common, is the summer-bearer. These produce one large crop of fruit once during the season, usually for about two weeks. Many people prefer these so that freezing and canning will be done once and put away, usually before gardeners are overwhelmed with the chores in the rest of the garden. Depending on your growing season and region, you can get early-, mid-, or late-season bearers.

Everbearers produce a crop in the spring, and then either produce smaller crops every six weeks or so or produce one more crop in the fall. If you want strawberries throughout the growing season, consider everbearers.

Alpine strawberries are the closest descendants of wild strawberries. They are perennial and are often grown as borders or even ground covers. Unlike the other types of strawberries, these plants can be grown from seed, and will bear throughout the growing season. Their fruit are small and often intensely flavored.

Most strawberry plants spread by sending out runners. Smaller plants grow on these runners. Many growers kill or remove the mother plant after a good fruiting season and then the daughter plants become the primary fruit bearers the following year. They in turn send out runners, and so on.

Varieties

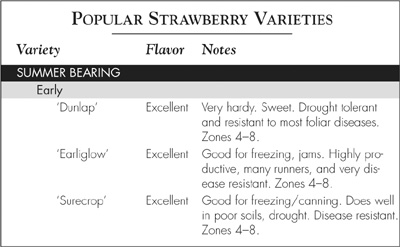

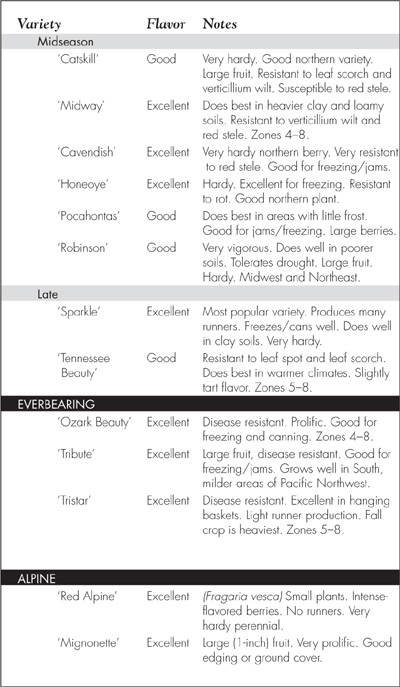

There are many strawberries to choose from. Decide whether you want summer bearing, everbearing, or alpine (or some combination of them) and then choose your plants according to your growing season, region, and special conditions.

Every variety has a different set of characteristics. Commercial growers look for varieties that are firm and will ship well. Sometimes they sacrifice taste for these qualities. Some berries are known for being large and perfect looking. Some are known for sweetness, and some freeze better than others. Growers for the restaurant market care about the look and color (both outside and inside) of the strawberry. Listed below are some of the most popular varieties and some general notes. For more details and other varieties, consult your local nursery, or see source list on page 31.

Climate and Conditions

Climate and local weather conditions affect the table quality of strawberry varieties, and it often varies greatly from season to season. Often it improves toward the end of the season.

Temperature. In New York and New England, Midway develops better quality than in Maryland. Sparkle is a good dessert variety in the North. Temperature also greatly affects the flavor of strawberries. Varieties grown where there are sunny days and cool nights have better flavor than those grown where there are cloudy, humid days and warm nights.

Firmness. Most varieties produce firmer fruit in cool temperatures. In New England, New York, and Michigan, Catskill and Sparkle produce a firmer fruit than they do farther south. In Maryland, they grow too soft for shipment.

Frost injury. Strawberries may escape frost injury if they blossom after most danger from frost has passed or if they have short blossom stems and blossoms that remain under protecting leaves. But varieties that have a long flowering season will develop some fruit despite frost. The flowers of Tennessee Beauty and Sparkle are late-blooming and are protected by leaves.

Varieties that escape frost more often are Pocahontas and Catskill. In the North and West, where frosts are unusually serious, everbearing strawberries are grown. If their first blossoms are killed, they produce a new set of buds.

Louise Riotte

Louise Riotte