Advance Praise for the Book

Cities and Canopies is packed with fun facts, engaging stories, and superb tales and factoids about Indian city treesPradip Krishen, author, environmentalist and film-maker

Just try this: Walk by or be driven through any city, refusing flatly to look at any building or read any hoarding, with your gaze fixed only on the trees you pass. The impact is amazing. They embrace you, engulf you and transport you into the world of their fragile fascination and that of our life in nature. Harini Nagendra and Seema Mundoli do precisely that through this gripping journey into the world of trees, so close to us and yet so spurned by our cement minds and steel eyes. One closes this book with just one thought: thank you, trees, for just being what you are, where you areGopalkrishna Gandhi, former IAS officer and former governor of West Bengal

Cities and Canopies is a splendid book about trees and their many associates, ranging from birds and bats, wasps and ants to skinks and snakes, with fascinating titbits about science, such as how trees communicate with each other with the help of the fungal network connecting their roots; about history, such as how Kabirs great banyan tree on Kabirwad Island in Bharuch might in fact be much older and be the one that Alexander described; about how humans relate to trees, including their roles in games and art; their medicinal uses and how to concoct a jamun squash. A very enjoyable read that I highly recommend to all lovers of nature, culture and foodMadhav Gadgil, ecologist, writer and columnist

This book challenges the urbanrural divide in our minds. It helps city dwellers understand the dangers of nature-deficit disorder and rediscover the biophiliaa love for naturethat exists in us all. Harini Nagendra and Seema Mundoli do this with joy, professionalism and deep knowledge. They introduce us to the secret language of nature, such as the silent communication between the glorious amaltas tree and its carpenter bee pollinators. They frame interesting questions such as can urban trees communicate with each other as well as those in forests? They also help us re-examine our animosity towards immigrant species, reminding us that the sriphala (the sacred coconut) and our very own tamarind are in fact exotics. A feast of a book, Cities and Canopies is timely and important for young people to read, and act uponRohini Nilekani, philanthropist, journalist, author and social activist

For three generations of my family who love trees: my grandmother, Thungabai; my mother, Manjula; and my daughter, Dhwani

Harini

To the frangipani tree of my childhood on whose branches my brother and I spent summer afternoons lazing, reading and planning our next adventure

Seema

ONE

A

KHICHRI

OF TREES

M ost of our grandparents were born in the villages of Indiamost of our grandchildren will be born in its cities. The entire world is experiencing a massive shift towards cities, and India is very much a part of this trend. One in every three Indians already lives in cities. In twenty to twenty-five years, one out of every two Indians will live in cities, with the total population in cities more than doubling in this short span.

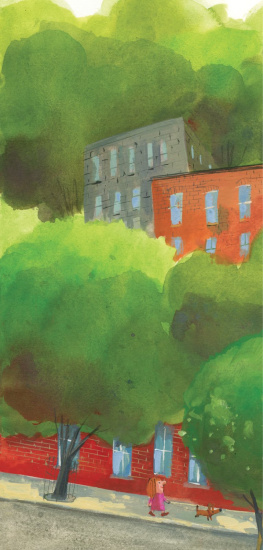

This fast growth of cities puts incredible pressure on the countrys ecology, as forests disappear, rivers and wetlands shrink into thin polluted slivers, and vistas of green and blue turn into horizons of concrete. But Indias cities are not divorced from nature. In fact, many of them are now greener than their surrounding areas. Over centuries, they have been assiduously planted with trees, greened and nurtured by successive kings and commoners.

Indias cities derive so much of their character, identity and liveability from the trees that grow there. From tree-lined streets where we shop for vegetables and clothes to wooded parks and playgrounds where children play and adults gather to walk while they talk and sacred trees at intersections where nature is worshipped in the heart of the madding crowdour cities would be unrecognizable, unliveable, without their trees.

Human choices and historical events have shaped the set of trees we see in each city. Most texts about ancient India describe towns encircled by rows of thorny trees, planted close together to protect the city from invasion. Within the city, public parks and waterbodies were landscaped with trees and flowering plants, while wealthy and royal households maintained residential gardens for private enjoyment. Orchards of fruiting trees provided fruit and income, while temples had groves of fruiting and flowering trees and plants. At street corners large trees were strategically planted, with platforms under them where people could sit together. Groves of large sacred trees like banyan and peepul provided serene sanctuaries outside the city walls, inhabited by saints and philosophers.

Other rulers entered with their influences. The Mughals brought in the idea of the Persian and Islamic gardens, which other rulers like Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan took to Mysuru, and the kings of the Bahmani Sultanate to the Deccan Plateau. The Marathas had their own style of gardens, as did the Rajputs. Portuguese, French and British colonialists added their own influences. In modern times, industrialists and landscapers have even brought in influences of faux Californian landscapes all the way from Silicon Valley. Our cities are now a fascinating mishmash, a khichri of trees, built on a base of local dal and rice but constantly infused with new ingredients and spices imported from different parts of the world.

We cannot imagine a life without trees. But trees mean different things to different people. A beautiful sequence in Asvaghoshas Buddhacarita (a first?second century CE poem on Gautama Buddhas life) describes women pointing out the trees in the garden of Padmakhanda, just outside the Sakya capital of Kapilavastu, to the Buddha.

See, my lord, this mango loaded with honey-scented flowers, in which the koel calls, looking as if imprisoned in a golden cage.

Look at this Asoka tree, the increaser of lovers sorrows, in which the bees murmur as if scorched by fire.

Behold this Tilaka tree, embraced by a woman with yellow body-paint. See the Kurubaka in full bloom, shining like lac just squeezed out, which bends over as if dazzled by the brilliance of the womens nails.

And look at this young Asoka tree, all covered with young shoots, which stands as if abashed by the glitter of our hands.

The romantic image of trees that this poem conjured was very different from the directions of Buddhas thoughts. He retreated from this conversation, eventually renouncing the city altogether and making his way to the forest in search of a higher truth.