To Mal

CONTENTS

Introduction

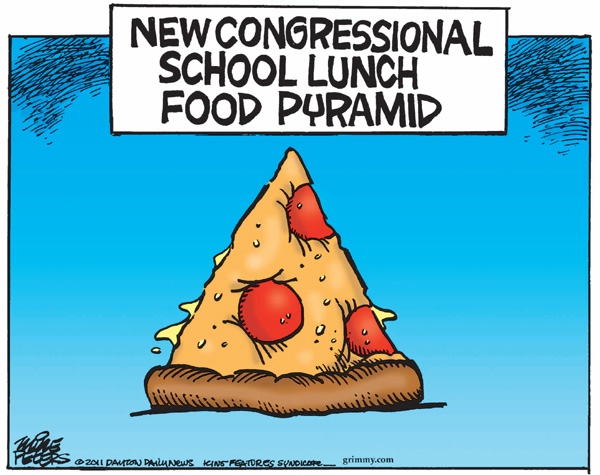

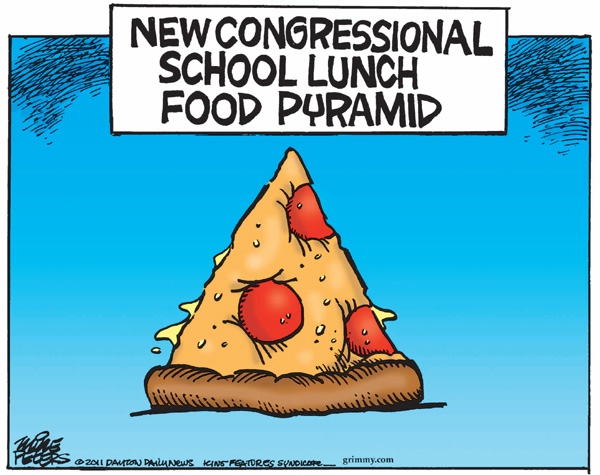

IN 2012, THE US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE (USDA) proposed new nutrition standards for meals served in school lunch programs. These specified the numbers and sizes of food servings necessary to meet childrens nutritional needs and promote health, but prevent obesity. One provision mentioned that tomato paste must meet the same volume requirements as other fruits and vegetablesone-half cupin order to be counted as a full serving. The makers of pizza for school lunches objected. This much tomato paste would make pizza soggy, they said. How best to make the USDA reverse this decision? Go to Congress, of course. Lobbyists for school pizza makers went to work. Bingo! The Senate inserted an amendment to the agriculture spending act, which authorizes funding for all USDA programs: None of the funds made available by this Act may be used to require crediting of tomato paste and puree based on volume.

The result? A dab of tomato paste on pizza now counts as a vegetable in school lunches. Kids get fewer servings of real vegetables in those lunches. Food companies now know that Congress will take care of them if they dont like federal regulations. And the public now knows that no regulationno matter how strongly recommended by nutrition and health experts and supported by researchis too small to be overturned by Congress to please corporate constituents.

I have written about such issues in professional articles and in my books devoted to food politics, food safety, supermarket choices, pet foods, and calories. I also write about such things on my (almost) daily blog, www.foodpolitics.com and in occasional tweets @marionnestle. But political cartoonists can tell the whole story in one drawing.

WHY AN ILLUSTRATED GUIDE TO FOOD POLITICS?

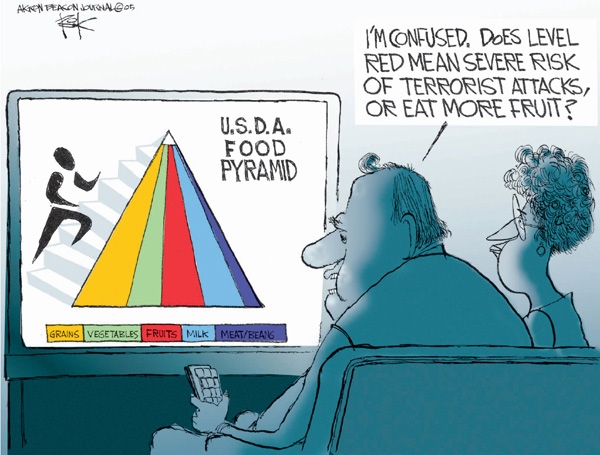

I LOVE FOOD CARTOONS. I started using them in my books in 2002 when I convinced the University of California Press to let me include a few drawings in the first edition of Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. The Press also agreed to publish cartoons in my subsequent book, Safe Food: The Politics of Food Safety, and in a later book on the safety of pet foods, Pet Food Politics. For decades, I have collected cartoons to use in my lectures to students and to the public. I am always looking for drawings that make it easier to explain complex concepts or points of view about food issues. That is how I first came across the work of some of the cartoonists represented in this book.

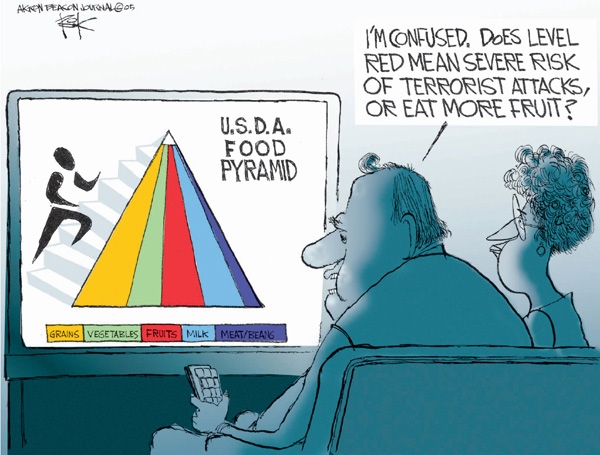

In 2005, for example, the USDA I show it, audiences get the point, laugh, and pay attention to the rest of my lecture. A great cartoon makes my work easierand a lot more fun.

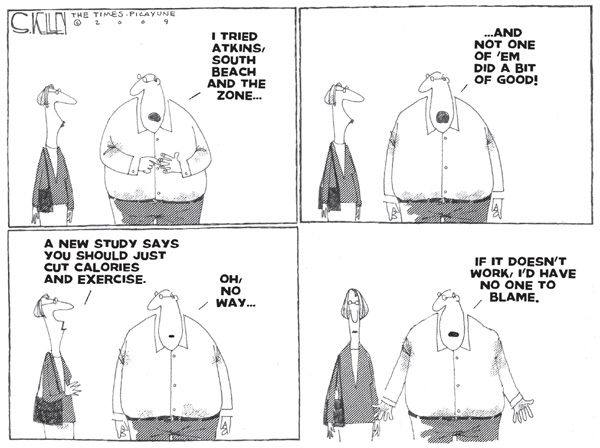

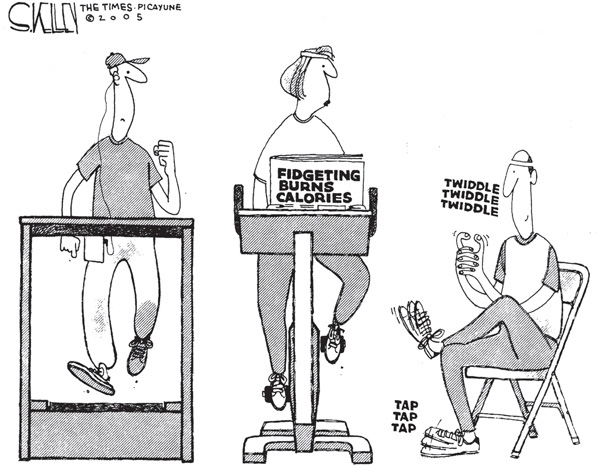

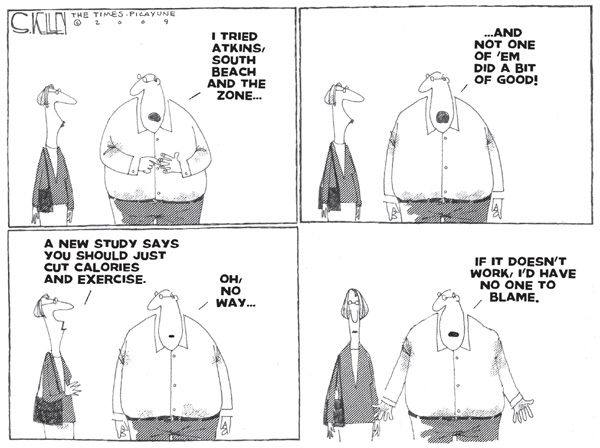

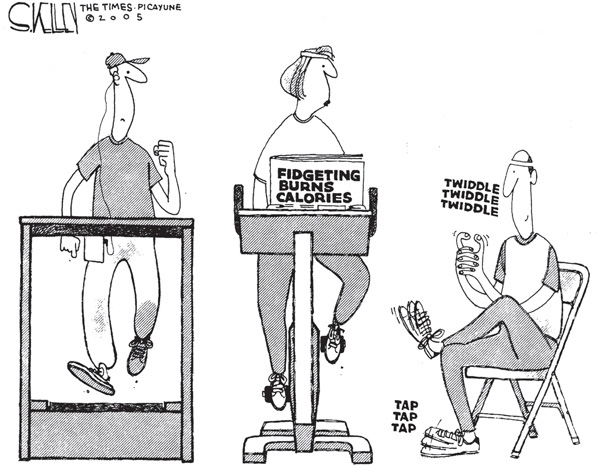

One more example: My most recent book (coauthored with Dr. Malden Nesheim) is Why Calories Count: From Science to Politics. It is about the most intangible of subjects. Calories cannot be seen, tasted, or smelled, and are difficult to measure accurately either in food or in the body. Mal and I struggled hard to make abstract scientific concepts accessible to general readers, and we wanted to include cartoons to lighten things up a bit. We found two that worked well. Both turned out to be drawn by Steve Kelley, who seems to have a particular interest in the same kinds of food issues that I do.

To republish Kelleys cartoons in our book, we had to obtain reprint rights to his work. This led me to the Cartoonist Group, which works with Creators Syndicate to license Kelleys drawings. The Cartoonist Group is owned and managed by Sara Thaves. Sara is a cartoonists legacy; her father created the comic strip Frank and Ernest, and her brother still produces it. She had already produced books with Cartoonist Group members Matt Wuerker (The Cartoonist Group Inks Campaign 08), Ann Telnaes (Dick), and Signe Wilkinson (One Nation under Surveillance). When I contacted her to ask about licenses and fees, Sara wondered whether I was the author of Food Politics. She had long wanted to showcase the food cartoons of artists in the group. Would I be interested? I most certainly would. I suspected that working with cartoons would be tremendous fun, as indeed it was. Sara and I talked. We met. This book is the result.

FOOD IS POLITICAL?

YES IT IS, as this book explains. Food is of extraordinary public interest. Everyone eats. In my writings about how politics influences what people eat, I approach the topic from the perspective of a public health nutritionist. Nutritionists teach individuals to make better food choices. But public health nutritionists take a broader view. We try to change the social, economic, and political environment so that it promotes the health and well-being of individuals. From a public health standpoint, food choices are not just personal decisions determined by cultural background, age, sex, peer group, education, or income. Food choices are also influenced by environmental factors. These include obvious ones such as advertising and marketing.

But they also include far more subtle influences such as product placement in supermarkets, portion size, price, and even how close at hand a food might be. The complexity and subtlety of these influences means that education alone is rarely enough to induce people to improve their diets. It works much better to change the food environment to make the healthier choice the easierthe defaultchoice.

This point, difficult to recognize as it may be, lies at the heart of current debates about food politics. Almost any aspect of food and nutritionfrom science to policy, from farm to forkgenerates controversy. Arguments about food issues derive from the complexity of foods and diets, and the uncertainty of the science linking diet to health. But the real reason for controversy is a difference in point of view. Dietary complexity and scientific uncertainty require interpretation. Interpretation depends on point of view. Point of view depends on cultural upbringing and value systems, but also on stakeholder position.

Because everyone eats, everyone has a vested interesta stakein how food is produced, sold, and consumed, and, therefore, in how food issues are interpreted. Stakeholders approach food issues from their own particular perspectives. Mine happens to be public health nutrition. I care about what it takes to promote health in the population as a whole, and I interpret both the science and the politics of food and nutrition from that point of view. From my public health standpoint, if government intervention in dietary choices improves health, it is a good thing to do.

I am well aware that not everyone shares this point of view. Americans particularly value personal autonomy, and many citizens believe that as long as their personal decisions do not directly harm others, the government should not interfere in what they choose to eateven if those choices eventually make them ill and generate health care costs that must be borne by society.