Margaret Davies, C.B.E., M.A., Ph.D.

John Gilmour, M.A., V.M.H.

Kenneth Mellanby, C.B.E., Sc.D.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EDITOR

Eric Hosking, F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The Editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native fauna and flora, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition in presenting the results of modern scientific research.

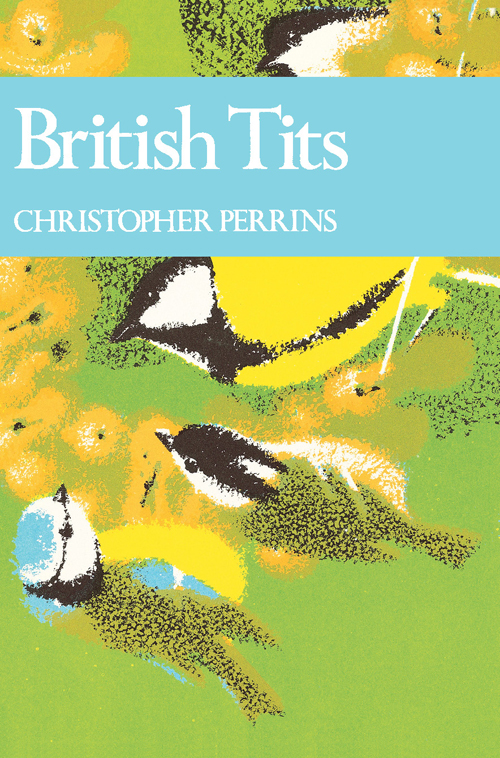

AFTER the Robin, the Blue Tit is probably the best-loved British bird. It is so small, so beautiful and so easy to observe. In the suburbs and even in many urban areas tits will appear, often in only a few minutes, if half a coconut, a bag of peanuts or a lump of suet is hung near a window. While it feeds, the birds acrobatics are a delight to watch, and have often cheered bedridden patients or elderly people unable to leave their homes. If a sparrow learns how to share the tits food, it is looked upon as an unwelcome intruder: we resent it consuming expensive items willingly provided for what we consider to be more attractive species.

A suitable nesting box erected in almost any suburban garden is likely to be occupied during the first spring that it is available by a Great Tit. When the eggs hatch the adults will be seen making repeated visits to the box, many times in an hour, to bring food to the young. They will often be observed to be carrying caterpillars, and this soon convinces the gardener that they are his allies, consuming the pests which would otherwise destroy his vegetables or defoliate his trees and shrubs.

The tits habit of pecking the top of milk bottles and drinking the cream may annoy the housewife, but it also convinces her of the birds cleverness. If she will not tolerate this minor inconvenience, she may persuade the milkman to put covers over the bottles he delivers.

Thus tits are birds which are particularly easy to observe at close quarters, when they are guests in our gardens. Nevertheless most of us know very little about their lives and habits, particularly about the majority of the birds which generally remain within their natural habitat deciduous woodland in the case of the Blue and Great Tits we so commonly entertain.

Dr Christopher Perrins, the author of this book, has studied tits for many years, particularly in Wytham Wood near Oxford. He has himself made many interesting and important discoveries about their behaviour and biology. His ability to communicate this information to specialist and non-specialist readers alike make him an ideal choice as a writer in the New Naturalist series. As well as incorporating his own work, he also gives full recognition to the work of many other ornithologists, in Britain and in other parts of Europe, and in Asia, where the species found in Britain also occur. He has thus produced a factual and authoritative account which should be of value and interest both to serious ornithologists and to those who wish to know something more about the charming birds they see so often in their gardens.

Seven different birds are here described in detail. These include six (Coal Tit, Great Tit, Blue Tit, Crested Tit, Marsh Tit, Willow Tit) which all authorities recognize as members of this group. Dr Perrins has also included the Long-tailed Tit, which purists consider only a distant relation. We believe that this inclusion is justified, particularly by the way in which comparisons between the true tits and the Long-tailed Tit are developed.

Dr Perrins shows us what is known about tits, and he also draws attention to many gaps in our knowledge. We hope that this will stimulate readers to make their own observations so as to increase further our understanding of some of the most attractive members of our natural wildlife.

PERHAPS this book should have been written many years ago; so much has been published on the European tits that it is difficult to synthesize it now. These small birds are so amenable to study that the journals are full of observations on them. Curiously, apart from a small work in 1846, no one until recently has tried to write a book covering all the British species.

It has been, therefore, quite impossible to try to include all that has been published about these birds. I have tried to cover the main topics, though doubtless others would have selected differently. Further, I have tried to keep the references from filling all the pages. The system of numbers should enable the reader to find the references that he wants to follow up, but at times he may have to look at the references in the paper to which I refer.

Most of the topics covered are inter-related and it is not always easy to decide where to put certain pieces of information. As a result I have allowed myself a certain amount of repetition in order that each chapter may be taken more or less on its own without the cross-referencing that would otherwise be required.

In particular, I have given a broad outline of the behaviour and life cycles of the tits in . Although much of this material is presented in greater detail later, it seemed important to put the outline here, before chapters 28 on the individual species. In these I have concentrated on features peculiar to the separate species. The reader who is more interested in the general biology of the birds than the detailed differences between the species might like to pass over these chapters, though he might still find chapter 8, on the Long-tailed Tit, worthy of examination.

So many people have contributed to the vast array of literature that this book could best perhaps be regarded as the outcome of an enormous piece of teamwork; the only advantage that the others have had is that they cannot be held responsible for the end product! One of the most pleasing aspects of working on tit populations has been the contact with other ornithologists, both in Britain and abroad. While we have disagreed (and still do!) about some of the basic factors which affect the birds at different stages of their lives, it has been a great pleasure to me to meet other workers in this field and discuss our work. In addition I owe a great amount to some of them for generously supplying me with their data for certain analyses.

Some of these debts cannot pass unnoted. My greatest debt is to the late Director of the Edward Grey Institute, Dr David Lack, F.R.S. David Lack was responsible for starting the study in Wytham Woods near Oxford and always took a keen interest in the studies of those who kept it going; his encouragement and friendly, helpful criticism are sorely missed. Outside Oxford, our closest contacts have been with the Dutch workers, especially the late Dr H. N. Kluijver, father of all current population studies of tits, having published a major work on them a quarter of a century ago and Dr J. H. van Balen. In Germany Dr H. Lhrls studies have been of great value to us.

Many others have kindly read and criticized earlier drafts of this book. Since some of these have done the key work in certain parts of the field they have in that sense provided the data also. I am particularly indebted to Dr D. Chitty, Dr E. K. Dunn, Dr M. C. Garnett, Dr A. J. Gaston, Dr J. A. Gibb, Dr. J. R. Krebs, Dr T. Royama, Dr D. W. Snow, Miss V. A. Wood and the late Dr M. I. Webber for their comments. Our main study area in Wytham Woods near Oxford has also been used by other ecologists. In particular a group of entomologists from the Hope Department, led by Prof. G. C. Varley and the late Dr G. R. Gradwell have studied the insects of the oak trees, a major food supply for the tits.

Next page