Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Copyright 2012 by Wolfgang Hadamitzky and Mark Spahn

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Third edition, 2011

Second edition, 1997

First edition, 1981

German language edition published in 1979

by Verlag Enderle GmbH, Tokyo; in 1980 by

Langenscheidt KG, Berlin and Munich

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data for this title is available.

ISBN: 978-1-4629-1018-2 (ebook)

Third edition

15 14 13 12 11 5 4 3 2 1 1111MP

Printed in Singapore

Distributed by

North America, Latin America & Europe

Tuttle Publishing

364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 U.S.A.

Tel: 1 (802) 773-8930

Fax: 1 (802) 773-6993

info@tuttlepublishing.com

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Japan

Tuttle Publishing

Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor, 5-4-12 Osaki

Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141 0032

Tel: (81) 3 5437-0171

Fax: (81) 3 5437-0755

sales@tuttle.co.jp

www.tuttle.co.jp

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd.

61 Tai Seng Avenue #02-12

Singapore 534167

Tel: (65) 6280-1330

Fax: (65) 6280-6290

inquiries@periplus.com.sg

www.periplus.com

TUTTLE PUBLISHING is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

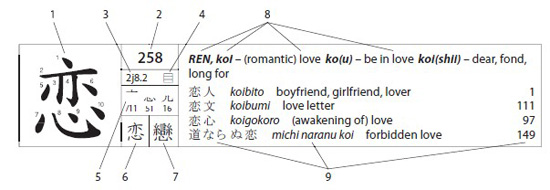

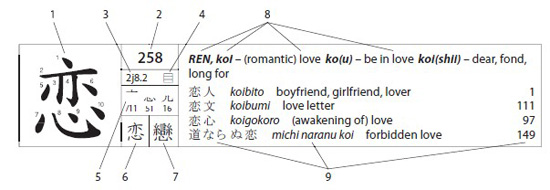

Explanation of the Jy Kanji Entries

- The kanji in brush form, with little numbers showing stroke order positioned at the beginning of each stroke.

- Running number identifying the kanji in this book (here, 258).

- Descriptor (2j8.2) of the kanji in character dictionaries using the 79-radical system. It consists of a radical designation (2j, for ), followed by the residual stroke count (8 = total stroke count 10 the 2 strokes of the radical), then a decimal point followed by a sequential number (2).

- Structure of the character (for a list of the different structures, see page ).

- Up to three graphemes (graphic elements of characters according to the online character dictionary KanjiVision) included in the kanji, with grapheme number (see the table of graph-emes on page ). A slash appears before the grapheme number (/11) if the first grapheme is the same as the radical in the printed character dictionaries that use the 79-radical system.

- The kanji in pen form (pen-ji) .

- Variant of the kanji (usually an obsolete form).

- Readings and meanings of the kanji, with on readings in uppercase italics, kun readings in lowercase italics, okurigana in parentheses, and rare or specialized readings in square brackets. As in the official Jy Kanji list, the first reading given is the one by which the kanji is alphabetized (in aiueo order); this is usually the kanjis most frequent on reading. Readings with the same meaning are listed together (REN, koi) .

- Example compounds and expressions in which the kanji is used, with transliteration, meaning(s), and cross-reference numbers to the entries for the other characters in the compound. The compounds are made up only of kanji that appear earlier and that you will have already studied if you learn kanji in the order presented in this book. In the few cases in which a kanji of a compound has no cross-reference number, it is not among the Jy Kanji .

The Kanji

Brief Historical Outline

The oldest known Chinese characters date back to the sixteenth century B.C., but their number and advanced form indicate that they had already gone through a development of several hundred years. Like the Egyptian hieroglyphics, the earliest Chinese characters started with simple illustrations, which during the course of time became increasingly abstract and took on forms better adapted to the writing tools of the time.

These characters, along with many other elements of Chinese culture, came to Japan by way of the Korean peninsula beginning in about the fourth century A.D., and since the Japanese had no writing of their own, the Chinese characters soon came to be used for the Japanese language as well.

At first these monosyllabic Chinese characters were used purely phonetically, with no reference to their meaning, to represent similar Japanese syllables:

This method enabled one to write down any word, but a single multisyllabic Japanese word required several Chinese characters, each consisting of many strokes.

A second method soon developed: the characters were used ideographically, with no reference to their Chinese pronunciation, to represent Japanese words of the same or related meaning:

Both methods are used in the Manysh , Japans oldest collection of poetry, dating from the eighth century. Here, words denoting concepts are written with the corresponding Chinese characters, which are given the Japanese pronunciation. All other words, as well as proper names and inflectional endings, are represented phonetically by kanji which are read with a Japanese approximation to their Chinese pronunciation. The characters used for this latter, phonetic function are called Manygana . The kana syllabaries developed from these characters after great simplification (see pages ).

For centuries, kanji, hiragana, and katakana were used independently of one another, and the number of symbols in use and their readings kept growing. Toward the end of the 1800s, after the Meiji Restoration, the government as part of its modernization program undertook to simplify the writing system for the first time.

The latest major writing reform came shortly after World War II:

1. In 1946 the number of kanji permitted for use in official publications was limited to 1,850 Ty Kanji (increased to 1,945 Jy Kanji in 1981 and to 2,136 Jy Kanji in 2010); of these, about 900 were selected as Kyiku Kanji to be learned in the first six years of schooling.

2. The on and kun readings of the Ty Kanji were limited in number to about 3,500 (increased to over 4,000 Jy Kanji readings in 1981, and to 4,394 readings in 2010).

3. Many kanji were simplified or replaced by others easier to write.

4. Uniform rules were prescribed for how to write the kanji (sequence and number of strokes).

The print and television press strives to follow these and other government recommendations concerning how Japanese is to be written. A knowledge of the set of characters treated in this book will therefore be sufficient for reading Japanese newspapers without time-consuming reference to a character dictionary. To be sure, this assumes mastery of a vocabulary of at least 10,000 Japanese words, most of which, including proper names, consist of two or three kanji. This is an important reason for learning kanji not in isolation but always in the context of multi-kanji compounds.

Since 1951 the government has from time to time published a supplementary list of kanji which, together with the Jy Kanji , are permitted for use in given and family names. Some of the characters in this list of kanji for use in personal names (Jinmei-y Kanji) are traditional kanji that were replaced with a simpler form in the reform of 1946 and for a time were therefore no longer allowed, even though many families preferred to write their names with traditional, unsimplified characters. According to Japanese law, only the kanji and readings that appear in these two lists may be used in given and family names. The first list of personal-name characters, which was issued in 1951, included 92 kanji; the latest list, issued in 2009, includes 985.