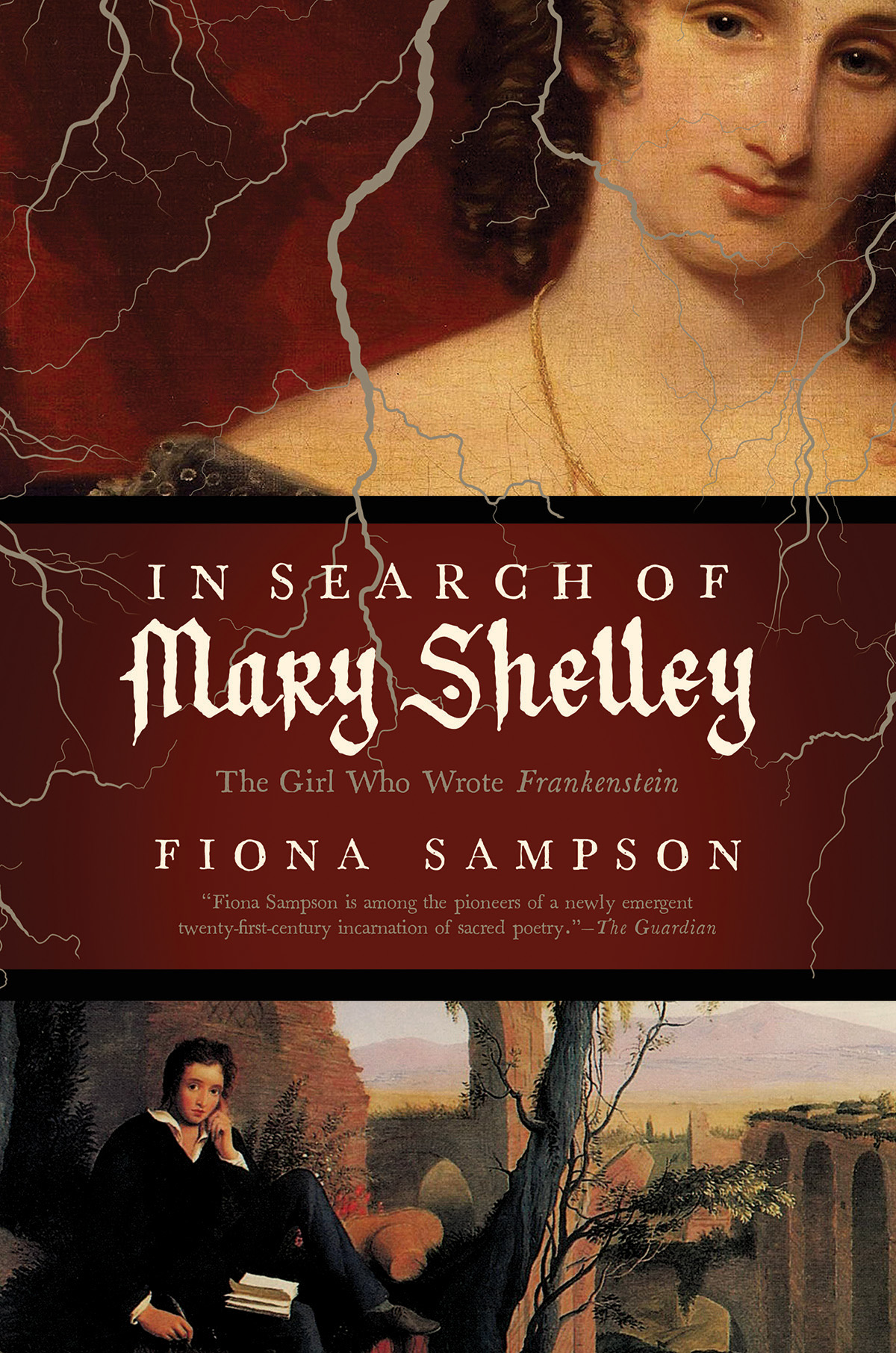

IN SEARGH OF

Mary shelley

FIONA SAMPSON

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

To examine the causes of life, we must first have recourse to death.

WE KNOW A GOOD DEAL about the circumstances of Marys birth in 1797, in an August bedroom in Middlesex, on the outskirts of London. We know, for example, that it is nearly midnight on 30 August, and that theres a smell of damp countryside coming in at the window on the night air. Attracted by the light, crane flies and moths skitter on the windowsill. The waxing moon is only just half full.

A new family the Godwins are grouped together at the bed. The healthy baby whos just been born is being introduced by her mother, the famous radical writer Mary Wollstonecraft, to the delighted father, fellow radical and philosopher William Godwin. Light from the households oil lamps brought upstairs for the tremendous occasion of this birth concentrates in all three faces, finding them the way it does in one of those studies of the Holy Family by Rembrandt, where lantern light falls out of a tender chiaroscuro darkness on to the family group. Rembrandts paintings tell us to trust the light because it finds where the action is, and is always on the side of the protagonists. And tonights lamplight gives everyone a healthy glow even as it covers up less attractive details, such as blood-stained sheets and towels, with tactful shadow.

The bedroom is at the top of a smart four-storey town house: actually there are five storeys if you count the garrets overhead. The house has only recently been built in low-lying, clay fields just north of London. On farmland to the east and south, ghostly roads have been marked up. A small grid of streets peters out between half-built shells, the bumpy outline of foundations, surveyors tape straggling between clumps of dock and nettle. In the dark it would be hard to tell whether these are ruins disappearing into the soil or new structures rising out of it. In fact, they are whats left of Brill Farm. Its upwardly mobile owner, Charles Cocks, recently elevated to become First Baron Somers of Evesham, has leased them to a local architect, Jacob Leroux, who has great plans as well as a fine track record. Hes already made a career on the south coast. But he also has a decidedly un-English name. Perhaps its for this reason or perhaps just to clinch the deal that he has flatteringly called the development that will surely make his own name after its landlord.

In the summer of 1797 Somers Town is not yet in the shadow of the still un-envisaged railways that will slice up this northern entrance to the metropolis. Tonight it remains an aspirational address, the sort of place where respectability can be invented and rehearsed until, with a bit of luck, it turns into security. This is an immigrant area, where many inhabitants are learning how to be bourgeois in the English way. Life here must sometimes feel like playing at house, and not only for newly-weds like the parents in our nativity tableau. There are strange clothes to try on. Contemporary Englishwomens fashion nods towards the neo-Classical in a way that echoes French Directoire style, with its high-pitched, largely exposed breasts; and Beau Brummell is cutting a high-society dash that puts pressure on men to keep up with their women. Then theres the odd diet. The British are obsessed with meat. Currently fashionable is the Revd Dr John Truslers 1788 tome The Honours of the Table (which includes a guide to the arts of carving so thorough that it will still be a key text in the 1930s). More coffee is being drunk in England than anywhere else in the world, but the ruinously expensive national drink is tea. In fact, so expensive has it become that a special offence of reusing tea-leaves has been created.

All this may seem like costume drama to us, but it is being played for real. The high stakes for these tenants include staying out of debtors prison, particularly in the current economic downturn. The Panic of 1796-7, though largely North American, has added to the strains already placed on the British economy by war with France, which has been dragging on since 1793. Indeed, when the architect of this whole ambitious development dies, less than two years from now, his executors will auction off the entire half-built estate. The sale that takes place at the Somers Town Coffee House on 30 June 1799 exposes shaky foundations to Jacob Lerouxs prosperity and to the district he has created: the whole held for long terms at very low ground-rents, part let on lease and part to tenants at will; the annual rental 62 8s. per annum. Even the sale announcement in The Times acknowledges that this does not amount to a profitable investment. Forty lots will be sold without the least reserve with no reserve price as will Lerouxs own capital spacious family home near by, with its coach-house, stable, and garden about three quarters of an acre. The chaotic, inconsistent system of tenancies he leaves behind reveals that Somers Town has Leroux in over his head: a gifted architect isnt necessarily a gifted speculator.

Its Leroux himself, for example, who tipped off baby Marys father about a cheap let going at 29 the Polygon. The tip-off seems characteristically generous on Lerouxs part, but it may also be politically motivated. Although hes Covent Garden born and bred, Lerouxs surname is undeniably French in origin. His mothers maiden name, Bonet, is French too. This may be coincidence, but its the kind that goes along with membership of a community. A century earlier, after the 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau made Protestantism in France illegal, up to fifty thousand Huguenots arrived in England. These were skilled migrants, glass and textile workers with the latest techniques up their sleeves, and they were welcomed with governmental and charitable subsidies, and by the naturalisation offered under the 1708 Foreign Protestants Naturalisation Act. In contrast, just the year before this story opens, the 1796 renewal of the Aliens Act has forced all migrs away from coastal areas, causing the thousands of more recent and Catholic refugees from the French Revolution of 1789 to settle in the English capital. Despite their religious differences, the Huguenot community is helping these newcomers. Somers Town is particularly welcoming: it has the closest housing to St Paneras Church, which is one of the few sites in London where Catholics can be buried. The Abb Carron, practical and spiritual leader of the local refugee community, lives at I the Polygon itself.

Tonights new mother is in a sense also a refugee from the Revolution. Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, who on the August night when she gives birth to her second daughter, Mary, is well known for the revolutionary A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), has recently escaped France with her first child, Fanny, who was born there. Her husband, William Godwin, anarchist and utilitarian, published the equally influential and similarly radical An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice just four years ago.

The couples new baby daughter will remain at 29 the Polygon for the first ten years of her life. During that decade Bloomsbury will fill the fields that at present lie beyond the new road to Paddington, and settlement will straggle up Paneras Place. Soon cheap rents and multiple occupancies will come to characterise a neighbourhood that symbolises the very opposite of respectability. Within thirty years of their construction its new houses will be a slum whose notoriety persists for a century and a half, into the eras of public housing, gang culture and the anxious socio-political footage of Shane Meadowss 2008 film

Next page