1. Big Things

Space is big. Really big. You just wont believe how vastly hugely mindbogglingly big it is. I mean you may think its a long way down the road to the chemists, but thats just peanuts to space.

Douglas Adams, godfather of modern scientific discourse

On the largest scale, we cant help but talk about space, things in space, and the colossal arc of time. Events in space happen on a time scale that makes geological time seem hurried, in no small part because it takes eons for anything to travel to anything else. Gravity, despite being a simple attractive force, twists the matter in the universe into a beautiful fractal of shapes, from light-seconds to tens of billions of light-years across.

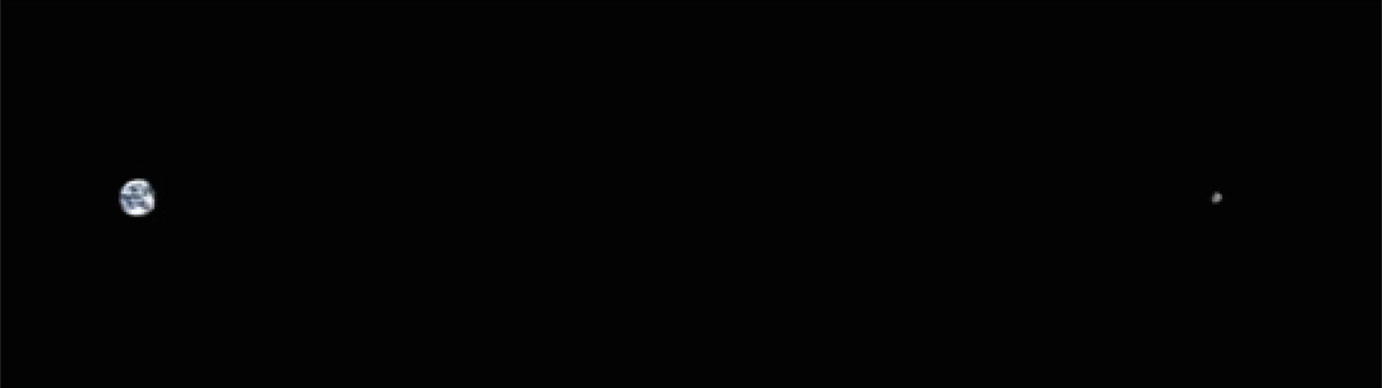

The defining characteristic of space, not surprisingly, is the amount of room it has and the profound dearth of things to fill it (Figure

Fig. 1.1

The Earth-Moon system (1:5,000,000,000 scale) is an unusually high concentration of matter in a universe that, despite containing everything, is profoundly empty .

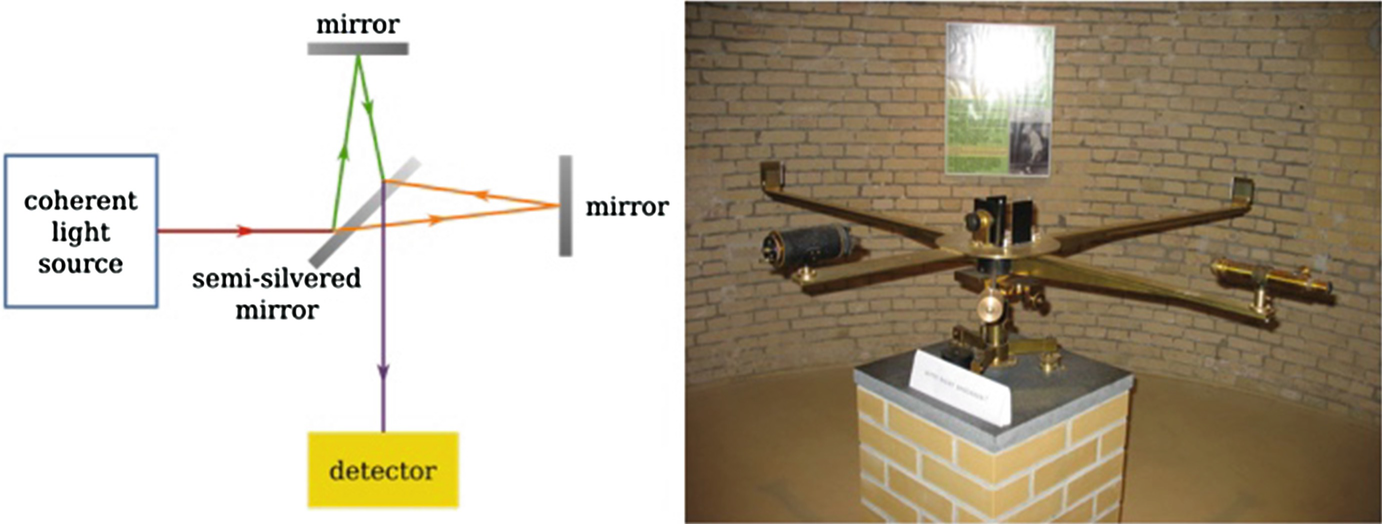

A key part of understanding the universe comes from relativity, which describes the nature of time and space themselves. For most of history, time and space were seen as a static stage; we could rest assured that the distance and duration between events was fixed. But a century ago, a strange, unshakeable property of light was becoming difficult to ignore: light always travels at the same speed regardless of how fast youre moving when you measure it (Figure ).

Fig. 1.2

The venerable Michelson-Morley experiment (1887): Despite being on a planet whipping around the Sun at 30 km/s (in a direction that changes throughout the year), Michelson and Morley found that light behaves as though the whole experiment were standing still. They sent light along perpendicular paths, recombined it, and observed an interference pattern. If anything had changed how long it took for light to make the journey along either path, the interference pattern would have changed. It didnt .

If light passes by at speed c , then youd expect that if you were running, it would pass you at c minus running speed. But it doesnt. It passes at c no matter what.

Speed is just distance over time (as in miles per hour). But since one particular speed, c , refuses to change for differently moving observers, distance and time have to change for them instead. Special relativity is the study of the interrelationship of time, distance, and the speed of light. It describes a universe with a bizarre underlying geometry that incorporates both space and time into a single framework ingeniously named spacetime.

Spacetime geometry isnt like Euclidean geometry Einstein discovered that the acceleration we feel from gravity is exactly the same as regular acceleration. In conjunction with the (at that time) new philosophies of special relativity, general relativity was born, ushering in our modern understanding of not just gravity, but the nature of the universe at large.

In space, gravity is the rule of the day and relativity is the key to understanding both. This chapter is about things in space, spacetime, and the universe itself.

1.1 What would Earth be like to us if it were a cube?

The Earth is really round. Its not the roundest thing ever, but its high on the list. If the Earth were the size of a basketball, our mountains and valleys would be substantially smaller than the bumps on the surface of that basketball. And theres a good reason for that. Rocks may seem solid, but on a planetary scale theyre squishier than soup. A hundred mile column of stone is heavy, so the unfortunate rocks at the bottom tend to pulp in a hurry. Part of what keeps mountains short is erosion, but equally important is that the taller a mountain is, the more it wants to sink under its own weight. So as a planet gets bigger and gains more gravity, the weight of the material begins to overwhelm the strength of that material, and the planet is pulled into a sphere (Figure ).

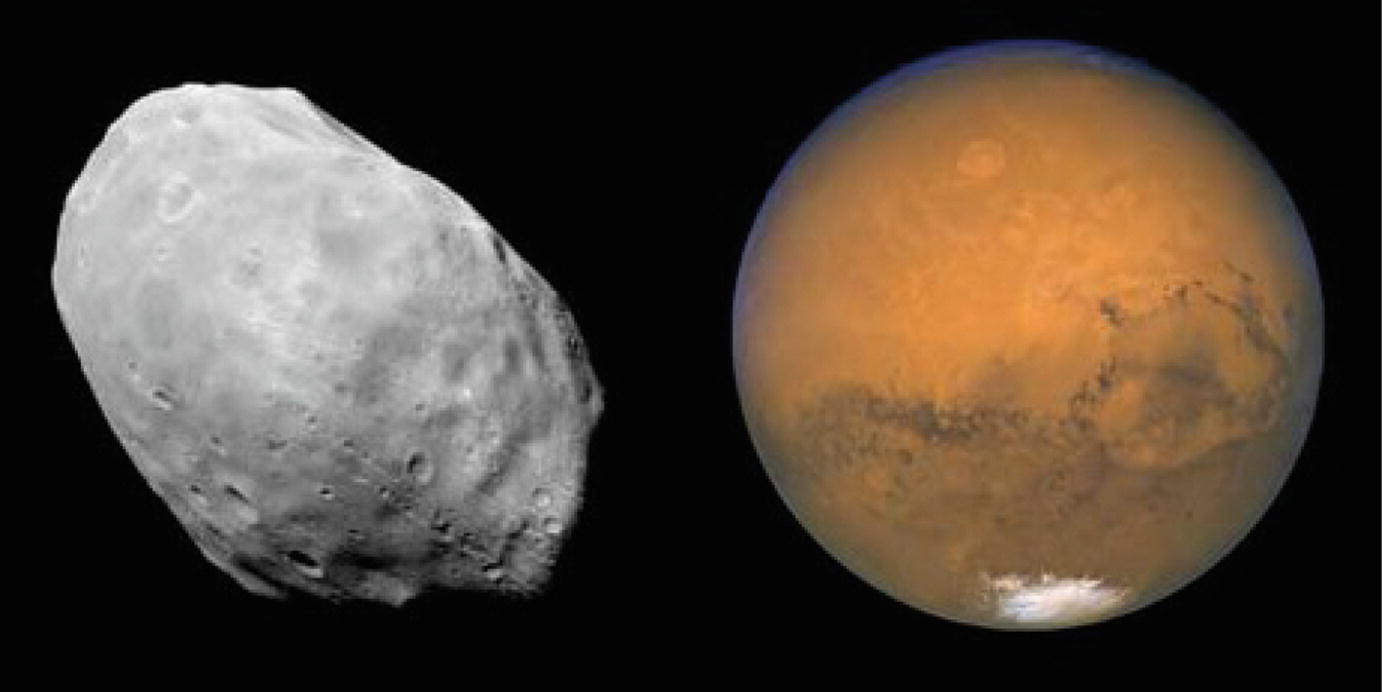

Fig. 1.3

Phobos (left), a very small moon about 20 km across, isnt big enough to generate the gravity necessary to crush itself into a sphere. Unlike its host planet Mars (right) .

So a tiny planet could be cube shaped (its not likely to form that way, but this is what hypotheticals are for). Something the size of the Earth, however, is doomed to be round.

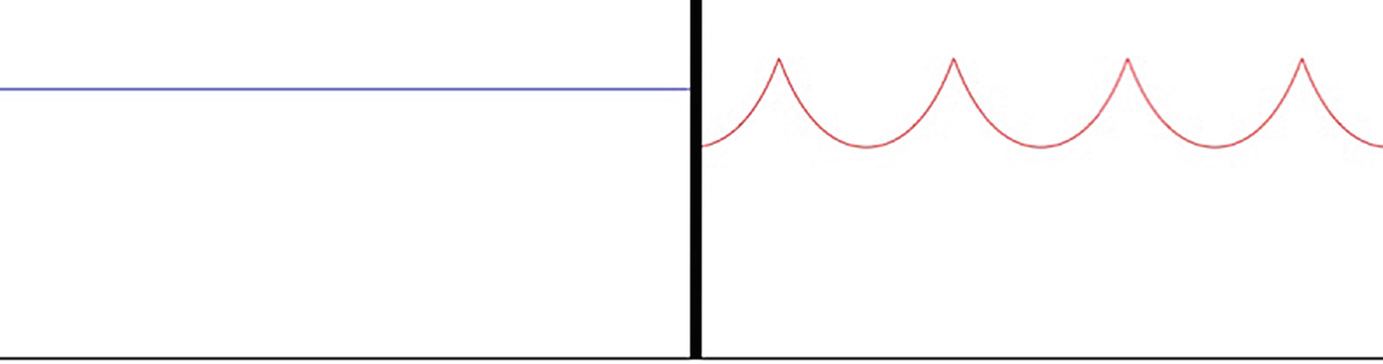

Life on a cubic Earth would be pretty different. Although gravity on the surface wouldnt generally point toward the exact center of the Earth anymore (thats a symptom of being a sphere), it will still point roughly in toward the center. The closer you are to an edge, the more it will feel as though youre on a slope. So, although it wont look like it, it will feel like each of the six sides forms a bowl. This has some very profound effects (Figure ).

Fig. 1.4

Distance to the center of the Earth vs. longitude. If you walk around the Earths equator (left) your altitude stays almost perfectly even. If you walk around the cube-Earths equator, cutting four of the faces in half, youd experience altitudes changes as great as 2,100 km. The eight corners of the cube would be a full 3,800 km higher than the centers of each face. For a sense of scale, Mt. Everest (a paltry 8.8 km) is shorter than these lines are thick .

Assuming that the seas and atmosphere arent held in place by the same mysterious forces holding the rock in place, they would flow to the lowest point they can find and puddle in a small region in the center of each face, no more than a thousand miles or so across. However, both the seas and atmosphere would be several times deeper; which doesnt count for as much as you might think. Here on Earth (sphere-Earth), once youre a mere five kilometers above sea level most of the air is already below you.

The majority of the cube-Earths surface would be vast, barren, and absolutely sterile expanses of rock exposed to space. If you were standing on the edge of a face and looked back toward the center, youd be able to clearly see the round bubble of air and water extending above the flat surface. I strongly suspect that it would be pretty.

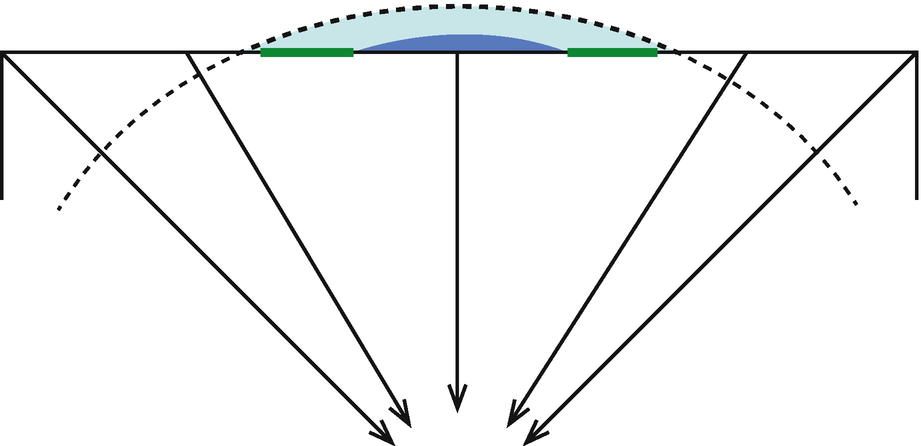

All life (land based life anyway) would be relegated to a thin ring around the shore of those bubble seas a couple dozen miles across (Figure ).

Fig. 1.5

A cross-section through a face. Gravity still points roughly toward the center of the cube-Earth (although in some areas it can point as much as 14 away from the center). As a result, the water (blue) and air (light blue) flows downhill and accumulates at the center of each face. This picture is way out of scale; there is no where near this much air and water on our Earth .