T here are more caddisfly species in Rocky Mountain waters than those of mayflies and stoneflies combined in the same region. Within Rocky Mountain habitats, including those in the Greater Yellowstone Area, caddisflies have adapted to a wide range of aqueous systems. They are most widespread in cool streams having some gradient. Streams of this type and in all sizes abound in the region, but caddisflies have also adapted to warmer and slower-moving streams. Some species inhabit stillwaters. Diverse and durable, they can tolerate less dissolved oxygen in waters than mayflies and stoneflies. Warmer water temperatures allow lower dissolved oxygen solubility and thus can be a measure of stream degradation. Although degradation of waters has happened for human reasons already mentioned in the introduction, warmer waters in the Greater Yellowstone Area happen mainly because of geologic conditions, such as found on the Firehole River, or because of temporary drought conditions. It must be remembered that most of the region receives less than 20 inches of precipitation a year, and that most of this is concentrated during winter.

Rhyacophilidae, Hydropsychidae, Glossosomatidae, Hydroptilidae, Brachycentridae, and Lepidostomatidae families of caddisflies are all represented in Greater Yellowstone Area waters. Within these families a large number of species are present, and one wonders why fly tiers have not created more specific patterns for caddisfly species. A good part of the answer to this question is biological as well as historical. Many of our fly-fishing and fly-tying traditions originated in the British Isles, where mayfly species are abundant and widespread. Caddisfly species there number less than fifty.

Caddisflies mature through four metamorphic stages (egg, larva, pupa, adult). The pupal stage is most important as an available food for salmonids; thus this stage is the major subject for fly tiers. Larval forms of caddisfly families can be free living, meaning swimming freely in water, or case building. Case builders make use of all kinds of detritus materials on stream bottoms. Casebuilding larvae are seldom imitated by fly tiers. Free-living pupal forms are most easily utilized by salmonids as food forms, so they are commonly simulated by tiers. Synthetic materials have done much for simulating larval and free-swimming and cased pupal forms. Adult caddisfly patterns are also a major subject for regional fly tiers.

Through scuba-diving observations, well known fly fisherman Gary LaFontaine saw that tiny air bubbles near the surface of emerging caddis give that insect a subtle sparkle. His subsequent discovery that the synthetic yarn Antron effectively simulates these air bubbles revolutionized the way caddis pupa flies are tied. Antron, a three-sided yarn, not only reflects light in a subtle manner, but it is also translucent. The influence of Garys discoveries, as explained in his benchmark book Caddisflies, has influenced how fly tiers everywhere simulate caddisfly pupae and free-swimming larvae. Thus the use of Antron, Z-Lon, or other yarns with equal reflective properties will be seen in many of the patterns described below.

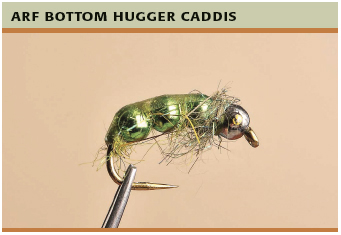

| Hook: | #10-14 TMC 2457 |

| Thread: | Olive-green 70-denier UTC Ultra Thread |

| Head: | Black stonefly Flymen Fishing Company tungsten head bead |

| Shellback: | Olive Scud Back, 1/8-inch wide caddis green Hares Ice Dub |

| Abdomen: | Three caddis green Flymen Fishing Company beads |

| Thorax: | Peacock Hares Ice Dub |

Al Ritt designed this fly to be bounced along the bottom, so one should carry a good supply of them while fishing. Als uncommon and clever use of several beads provides a segmented appearance and adds sparkle for this deep-water fly. He dead-drifts it alone or fishes it as an anchor in any two-fly rig.

| Hook: | #10-18 TMC 2457 |

| Bead: | Gold |

| Weight: | Twelve to fifteen wraps of 0.020-inchdiameter lead or lead-free wire |

| Thread: | Olive 70-denier |

| Rib: | Gold tinsel |

| Tail: | Copper Antron yarn |

| Abdomen: | Peacock Spectra Dubbing |

| Underwing: | Copper Antron yarn |

| Wing: | Olive Swiss Straw |

| Thorax: | Peacock Spectra Dubbing |

| Hackle: | Partridge flank |

Tim Wade designed this pattern (ATT is for All the Time Emerger) for the heavy current streams in the Greater Yellowstone Area. These streams abound in caddisflies, a major food item for resident salmonids. The buggy appearance and color are important for these durable patterns. Tim offers the olive (green) version, described and pictured above; and a tan version in which tan dubbing (abdomen and thorax) replaces olive dubbing, brown Antron yarn (tail) replaces copper Antron yarn, and a few white hackle fibers are added to the underwing.

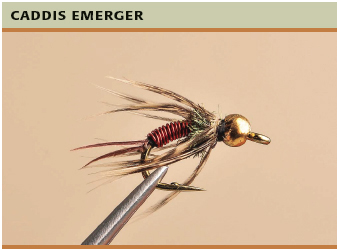

| Hook: | #8 TMC 2457 |

| Bead: | Gold, 5/32-inch diameter |

| Thread: | Black 8/0 UNI-Thread |

| Tails: | Duck biot tips |

| Body: | Fine red UNI-Wire |

| Thorax: | Peacock herl |

| Wing case: | Pearlescent holographic tinsel |

| Hackle: | Hen pheasant flank feather |

During the several years he lived in West Yellowstone during vacations, Jim Fisher experienced the wonderful fishing that surrounded the town. He tied flies to meet each of the many food forms available to resident salmonids. This pattern, his favorite caddis emerger, makes a different use for red wire that is popular in patterns imitating bloodworms. Jim found his pattern to be effective throughout the season during caddis emergences from the Madison River and the Henrys Fork.

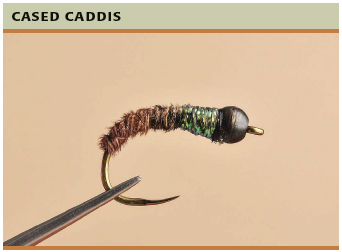

| Hook: | #8-12 TMC 2499SPBL |

| Bead: | Gold or black |

| Thread: | Black or green 3/0 or 6/0 |

| Rib: | 4X monofilament |

| Body: | Pheasant tail fibers |

| Thorax: | Green Krystal Flash or Flashabou twisted around tying thread for strength |