In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Thank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

Sign Up

Or visit us at hachettebookgroup.com/newsletters

For more about this book and author, visit Bookish.com.

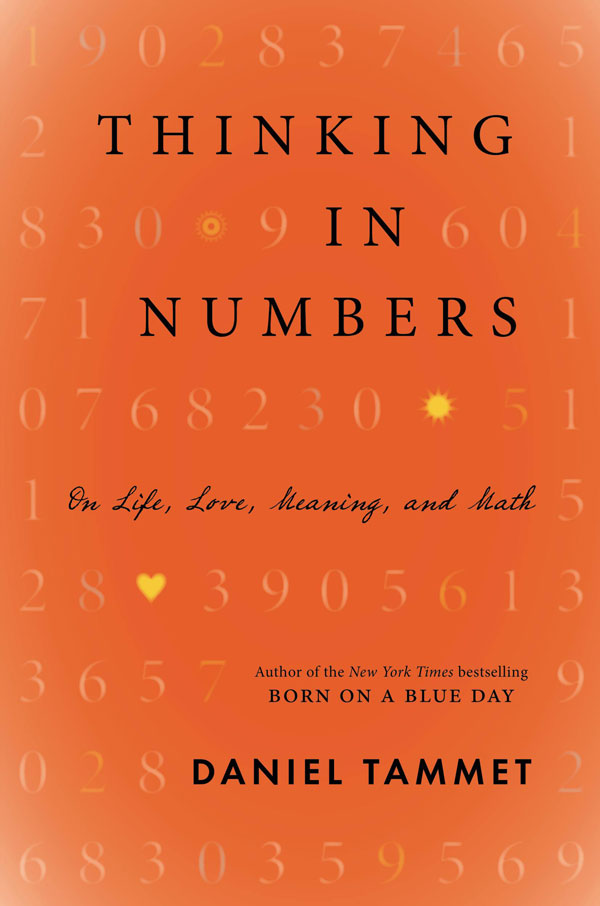

Copyright 2012 by Daniel Tammet

Cover design by Kimberly Glyder

Cover 2013 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: July 2013

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Excerpt from The Lottery Ticket by Anton Chekhov; excerpts from Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov Vladimir Nabokov, published by Orion Books, used by permission; excerpt of interview with Vladimir Nabokov was taken from the BBC program Bookstand and is used with permission; excerpts by Julio Cortzar from Hopscotch, Julio Cortzar, published by Random House New York; quote from The Masters Eye translated by Jean de la Fontaine; quote from Under the Glacier by Halldr Laxness, Halldr Laxness, published by Vintage Books, an imprint of Random House New York.

ISBN 978-0-316-25080-1

Born on a Blue Day

Embracing the Wide Sky

To see everything, the Masters eye is best of all,

As for me, I would add, so is the Lovers eye.

C AIUS J ULIUS P HAEDRUS

Like all great rationalists you believed in things that were twice as incredible as theology.

H ALLDR L AXNESS , U NDER THE G LACIER

Chess is life.

B OBBY F ISCHER

E very afternoon, seven summers ago, I sat at my kitchen table in the south of England and worked on a book. Its name was Born on a Blue Day. The keys on my computer registered hundreds of thousands of impressions. Typing out the story of my formative years, I realized how many choices make up a single life. Every sentence or paragraph confided some decision I or someone elsea parent, teacher, or friendhad taken, or not taken. Naturally I was my own first reader, and it is no exaggeration to say that in writing, then reading the book, the course of my life was inexorably changed.

The year before that summer, I had traveled to the Center for Brain Studies in California, where the neurologists probed me with a battery of tests. It took me back to early days in a London hospital when, surveying my brain for seizure activity, the doctors had fixed me up to an encephalogram machine. Attached wires had streamed down and around my little head, until it resembled something hauled up out of the deep, like anglers swag.

These scientists wore tans and white smiles. They gave me sums to solve, and long sequences of numbers to learn by heart. Newer tools measured my pulse and my breathing as I thought. I submitted to all these experiments with a burning curiosity; it felt exciting to learn the secret of my childhood.

My autobiography opens with their diagnosis. My difference finally had a name. Until then it had run the whole gamut of inventive aliases: painfully shy, hypersensitive, cack-handed (in my fathers characteristically colorful words). According to the scientists, I had high-functioning autistic savant syndrome: the connections in my brain, since birth, had formed unusual circuits. Back home in England I began to write, with their encouragement, producing pages that in the end found favor with a London editor.

To this day, readers both of the first book and of my second, Embracing the Wide Sky, continue to send me their messages. They wonder how it must be to perceive words and numbers in different colors, shapes, and textures. They try to picture solving a sum in their mind using these multidimensional colored shapes. They seek the same beauty and emotion that I find in both a poem and a prime number. What can I tell them?

Imagine.

Close your eyes and imagine a space without limits, or the infinitesimal events that can stir up a countrys revolution. Imagine how the perfect game of chess might start and end: a win for white, or black, or a draw? Imagine numbers so vast that they exceed every atom in the universe, counting with eleven or twelve fingers instead of ten, reading a single book in an infinite number of ways.

Such imagination belongs to everyone. It even possesses its own science: mathematics. Ricardo Nemirovsky and Francesca Ferrara, who specialize in the study of mathematical cognition, write that like literary fiction, mathematical imagination entertains pure possibilities. This is the distillation of what I take to be interesting and important about the way in which mathematics informs our imaginative life. Often we are barely aware of it, but the play between numerical concepts saturates the way we experience the world.

This new book, a collection of twenty-five essays on the math of life, entertains pure possibilities. According to the definition offered by Nemirovsky and Ferrara, pure here means something immune to prior experience or expectation. The fact that we have never read an endless book, or counted to infinity (and beyond!) or made contact with an extraterrestrial civilization (all subjects of essays in the book) should not prevent us from wondering: what if?

Inevitably, my choice of subjects has been wholly personal and therefore eclectic. There are some autobiographical elements but the emphasis throughout is outward looking. Several of the pieces are biographical, prompted by imagining a young Shakespeares first arithmetic lessons in zeroa new idea in sixteenth-century schoolsor the calendar created for a Sultan by the poet and mathematician Omar Khayym. Others take the reader around the globe and back in time, with essays inspired by the snows of Quebec, sheep counting in Iceland, and the debates of ancient Greece that facilitated the development of the Western mathematical imagination.

Literature adds a further dimension to the exploration of those pure possibilities. As Nemirovsky and Ferrara suggest, there are numerous similarities in the patterns of thinking and creating shared by writers and mathematicians (two vocations often considered incomparable). In the Poetry of the Primes, for example, I explore the way in which certain poems and number theory coincide. At the risk of disappointing fans of mathematically constructed novels, I admit this book has been written without once mentioning the name Perec.

Next page