Storm Dunlop - How to Read the Weather

Here you can read online Storm Dunlop - How to Read the Weather full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Pavilion Books, genre: Children. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:How to Read the Weather

- Author:

- Publisher:Pavilion Books

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

How to Read the Weather: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How to Read the Weather" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

How to Read the Weather — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How to Read the Weather" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Snow at Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire.

A glorious day at Felbrigg Hall, Norfolk.

Having the right weather is important to so many of our activities, yet sometimes it seems the weather forecasters are always getting it wrong. Occasionally their forecasts are wildly inaccurate, but more often there are little differences that can mess up our plans: rain when none was expected spoils our day at the beach, or a fine, sunny day when the local forecast had said showers means well have to water the garden after all.

To be fair, weather is one of the most complex phenomena that we experience, and creating correct forecasts is an exceptionally difficult task. People have been trying to do it since at least the Babylonians, who in around 3000BC were trying to predict weather using astrology the position of the moon and the planets in the sky and weather lore. Even today, weather forecasting is possibly the most complex scientific problem that exists. But it has improved significantly in recent decades, with modern supercomputers used by the majority of major meteorological offices. In fact, the overall pattern of their weather predictions is essentially correct. Its in the details of local weather that problems still arise. Despite all the major advances in forecasting, as yet none of the models are able to account for the minor local variations that can put paid to our plans for the day.

Predicting local weather is a minefield. Knowledge of the features that may affect local weather hills or mountains, bodies of water, and also human activities may help to supplement the official forecasts, but these weather complications may themselves introduce considerable variations. And it is impossible to focus on local weather without also bearing in mind the global influences at work. Even the less changeable local areas are subject to the same global processes that govern the weather as a whole.

Britains weather is subject to a wide variety of influences. It has a maritime climate, from being located on the western edge of Europe, bordered by the Atlantic. A warm ocean current, the North Atlantic Drift, brings moist, warm air. As a result it has generally mild weather in both summer and winter, but it also has highly variable local weather.

Weather is the condition of the atmosphere, which we describe colloquially as sunny, rainy, snowing, hot or cold. The basic factors that make weather are temperature and pressure, as well as the behaviour of water in the atmosphere. It pays to understand all these more fully, and how they interact.

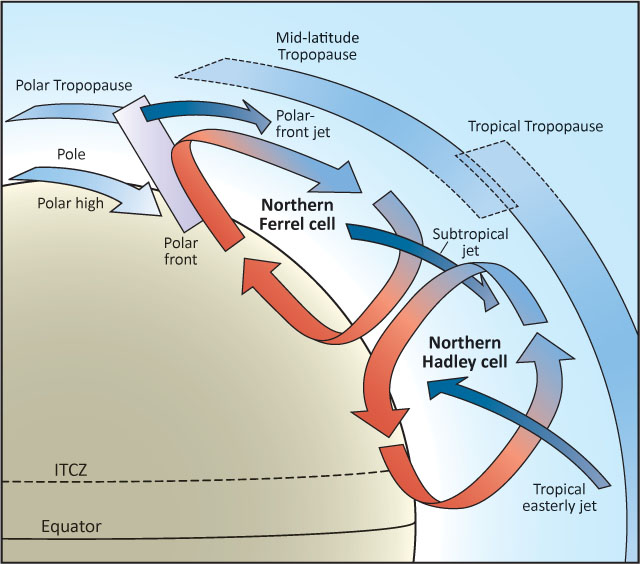

The Earths weather systems are ultimately driven by the difference in heating between equatorial regions and the poles. Radiation from the Sun heats the Earth unevenly, and any given area at the poles receives far less heating than a similar area at the equator, which creates strong temperature differences. Warm air at the equator expands and rises, creating low pressure at the surface while the colder air at the poles contracts, creating higher pressure at the poles. The imbalance between the temperature and pressure at different latitudes creates the overall circulation.

In the early days of studying the weather, people thought that warm air rising in the tropics flowed north and south, then descended in the polar regions as cold air, after which it flowed back to the equatorial region all within a single circulation system. But it wasnt long before meteorologists realised that there are actually three major circulation cells that form wind belts around the Earth: from the equator to the mid-latitude high-pressure areas (known as the Hadley cell), a mid-latitude cell (the Ferrel cell), and a polar cell. These three cells exist in both northern and southern hemispheres with an accompanying pattern of high- and low-pressure areas. There will be more about them in . The way these systems move and govern the weather we experience is determined by the overall pattern of the winds.

Expansion and Contraction

Both expansion and contraction of air, and how they relate to temperature, are important in understanding the weather and, for example, how clouds form. Air cools as it expands and warms as it is compressed. A couple of everyday examples make this clearer. When you pump up a tyre, the pump becomes hot as the air is compressed through the pump into the tyre and its kinetic energy (its heat) increases. But when you let air out of a tyre, it feels cold as pressure is released and the air expands in the same way, the air or propellant from an aerosol can feel cold when it is released from the pressurised container.

Air rising in the equatorial region creates a belt of low pressure at the surface, known to sailors as the Doldrums, where winds are light and greatly variable or even non-existent. This air flows north and south high in the atmosphere, finally descending at latitudes of approximately 30N and 30S. As air descends it becomes compressed and warms (more detail on this all-important feature later), producing high-pressure regions at the surface. In this particular case the high-pressure belts created are known as the subtropical anticyclones or subtropical highs. The descending air becomes dry and hot, and the Earths major deserts are located at these latitudes. In the northern hemisphere there are the Sahara and Arabian Deserts, as well as the desert areas in North America. (The Sahara is the source of the hottest air that reaches Britain and the western part of Europe.) In the southern hemisphere there are smaller land areas compared with the vast extent of the Southern Ocean, so this means there are smaller desert regions, most notably the Namib and Kalahari Deserts in southern Africa, and the Great Australian Desert.

Surface air flows out from the subtropical high-pressure belts and much of it returns back towards the equatorial regions, setting up a consistent flow. This forms what are known as the trade winds, which blow mainly from the north-east in the northern hemisphere and from the south-east in the southern. The northern and southern trade winds meet up in the equatorial region, and this important boundary is known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). A bit of a mouthful to remember, but actually you can quite easily see it on satellite images of the Earth as a distinct line of clouds. The trade-wind zones typically show shallow cumulus clouds, which are limited in their upward growth by an inversion (see ) created by air subsiding above them.

Where the Wind Blows

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How to Read the Weather»

Look at similar books to How to Read the Weather. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How to Read the Weather and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.