All Fourths Tuning for Jazz Guitar

(for noobs and nerds alike)

Yasser Mattar, PhD

Copyright 2020 by Yasser Mattar

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

All scores and tablatures were written on MuseScore (musescore.org).

Cover design by Felix Oking.

ISBN: 9781672547185

Contents

M usic is composed of four pillars: melody, harmony, rhythm and timbre. This book is primarily premised on the first two, at the outset. Tuning ones guitar to fourths allows one to see the fretboard in a simplified and logical way, according to Stanley Jordan (cited in Jim Fergusons article Stanley Jordan in Helen Casabona and Adrian Belews book New Directions in Modern Guitar ). This simplified and logical sequencing allows melodic lines to be clarified visually. It also allows for harmony, in the form of chords and chord voicings, to be clearly visualized according their intervallic qualities.

Rhythm has no place in tuning. It does, however, have a place in jazz. Adam Neely in his video How and Why Classical Musicians Feel Rhythm Differently (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rEbUNDW9bDA) strongly suggests that classical musicians react to rhythm while jazz musicians internalize rhythm. For this very reason, I believe that rhythm is of utmost importance to jazz and it would be as near a capital crime as it can get for me to leave rhythm out of this book. In this book, I have embedded rhythm into our discussions of how to apply all fourths tuning in musical contexts, such as the walking bass, Latin jazz, rubato and elsewhere.

Timbre is something that I do not account for at all in this book. Timbre concerns the quality of the sound that distinguishes one instrument from another. Scientifically, it involves the relative pitches of overtones produced by the instrument in question, as well as the attack, sustain and decay of those overtones. It also distinguishes the mid frequencies of bebop from the trebles of early black metal and the bass frequencies of brostep. However, I seek solace in the understanding that one can tune ones guitar in all fourths and play jazz without needing to account for timbre much.

This book is meant for noobs as well as nerds. Noobs need only read the introduction to every section, and find meaning in the diagrams and sheet music provided. There will be words which confuse noobs but honestly, did you really understand every word in your comic books when you first read them when you was but a young whipper-snapper? No? Well, the same applies here. Nerds will be given servings of nerd sauce, sometimes quite liberally. I do tend to pour the sauce on pretty thick, but I guess thats how jazz theorists like their biscuits. Soaked in sauce.

This book will firstly look at an introduction to all fourths tuning and try to convince you to tune to all fourths. It will then look at the simplified and logical nature of scales, chords and the walking bass. This knowledge will then be applied to arranging songs in all fourths tuning.

I hope that this book opens up a whole new world of possibilities for your guitar playing and convinces you that all fourths tuning is suitably suited for jazz guitar. I also hope that you gain deeper insights into jazz theory beyond your current realm of understanding. Most of all, have fun! To quote Americana virtuoso Bob Brozman, in every language I've ever encountered, they say play music, not work music (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q2p52JNcbDc).

What is all fourths tuning?

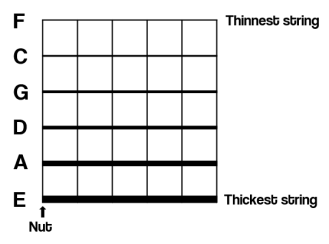

A ll fourths tuning refers to tuning ones guitar such that the intervals between the stings ascend in fourths. The diagram below shows how to tune ones guitar to fourths.

I n standard tuning , the guitar is tuned to E-A-D-G-B-E. There are also many other alternative tunings aside from fourths, such as open tunings, where the strings are tuned to an open chord (for example, D-A-D-F-A-D or D-G-D-G-B-D).

Nerd sauce: Intervals which ascend in fourths sound airy and open. In non-jazz circles, this feeling tends to be described as suspended because it is not resolved to either the 3rd or flatted 3rd scale degrees. Ascending in fourths also necessarily means that the intervals descend in fifths. Intervals in fifths sound strong and firm. Think of how strong and firm power chords (used liberally in rock and metal) sound in order to get an idea of this. However, because intervals are heard by the ear in ascent, the strength of the intervallic fifths in descent are not discerned.

Why should one tune to fourths?

- Chord shapes are uniform across string sets as well as horizontally along the neck

- Scale shapes are uniform across string sets as well as horizontally along the neck

- Arpeggio shapes are uniform across string sets as well as horizontally along the neck

- Its ergonomic

- One has control over voicings

- One has control over the intervals in voicings

- Its easy to make quartal chords, a mainstay in the jazzy sound

Moving across string sets and along the neck

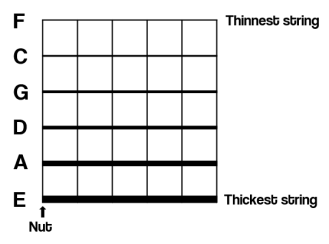

C hord shapes, arpeggio shapes, scale shapes and intervals look the same across string sets and along the neck. Aint that grand? The example below shows how a drop 2 voicing of a major 7 chord can be moved across string sets and horizontally along the neck.

Next page